About

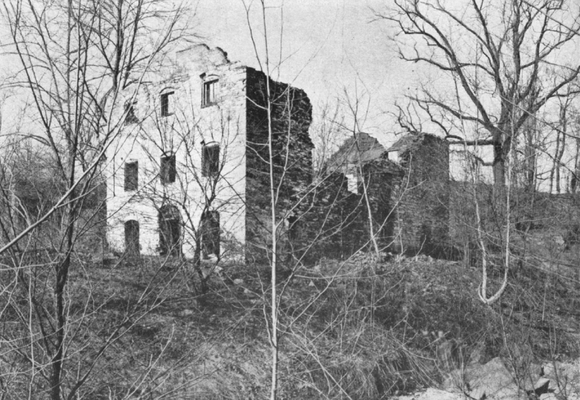

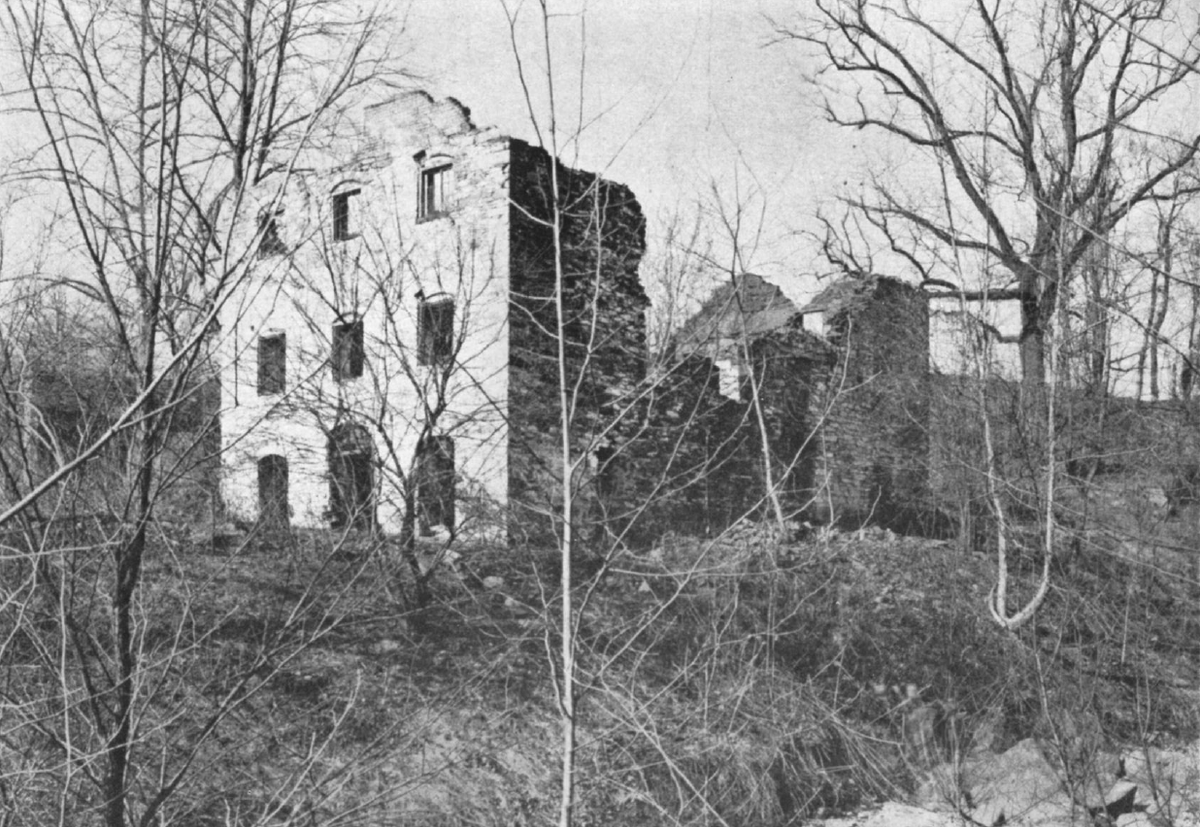

The National Parks Service hasn’t had a chance yet to erect an explanatory plaque beside newly uncovered ruins in the overgrowth along the Potomac River. The nondescript stone walls don’t offer many hints about their former purpose, but historic maps of the area—located between Foxhall Road and Foundry Branch Valley Park—reveal the location’s past use by D.C.’s first defense contractor.

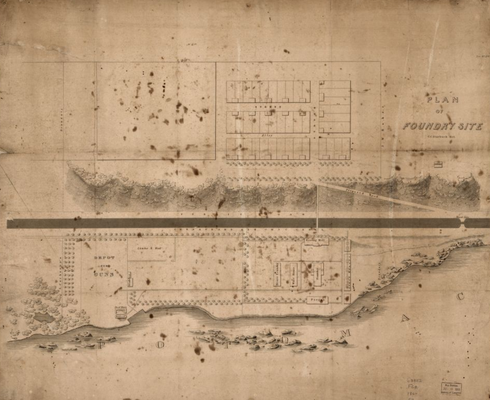

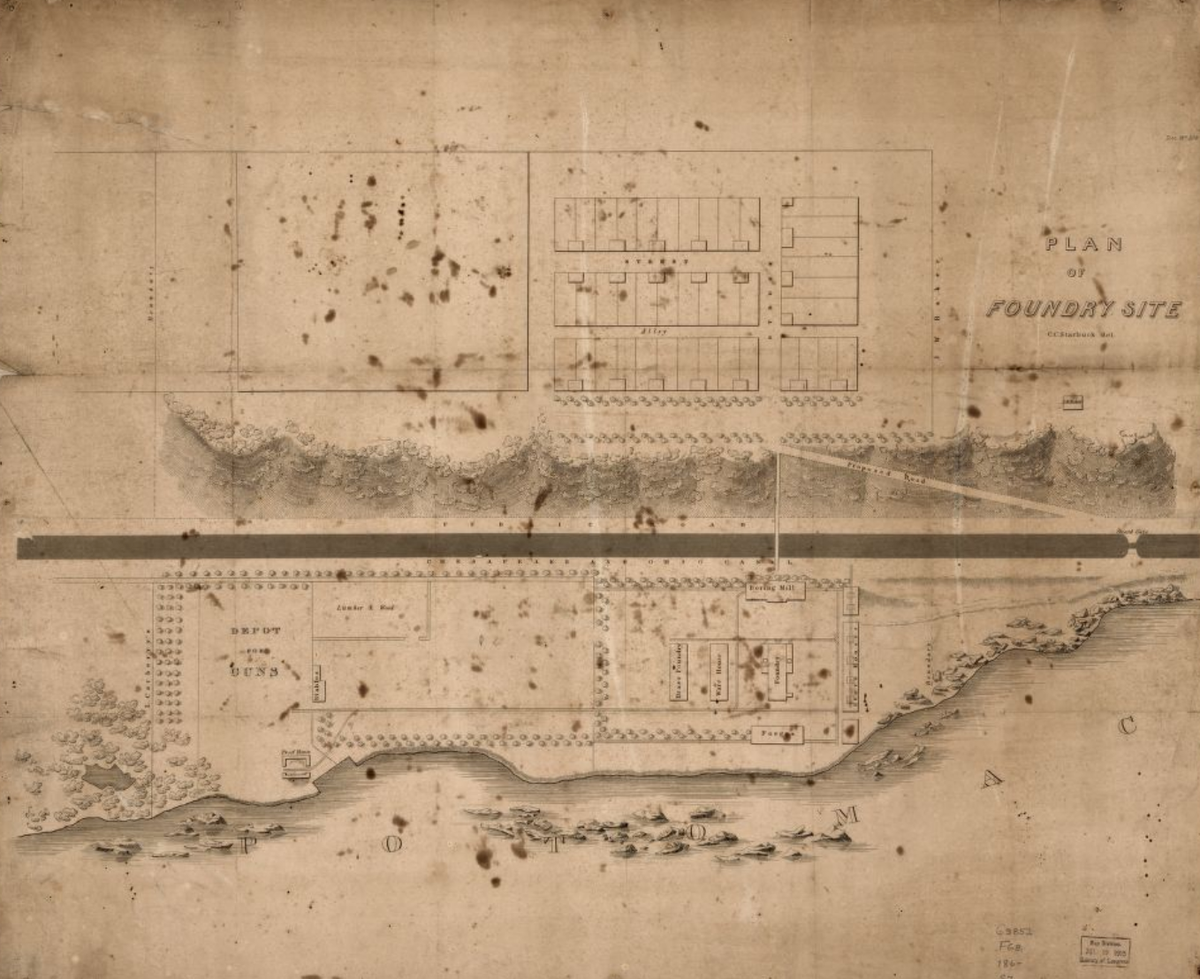

Though the riverbank west of Georgetown University is today dominated by parklands, it was once a nexus of 19th-century industrial activity: canal traffic, ice factories, and mills were present, as well as the B&O railspur that later carried coal to the government power plant in Georgetown. A largely forgotten cannon factory once stood at the site of recently uncovered stone.

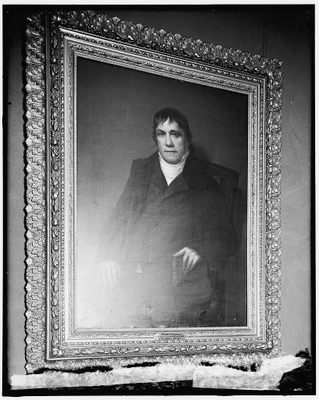

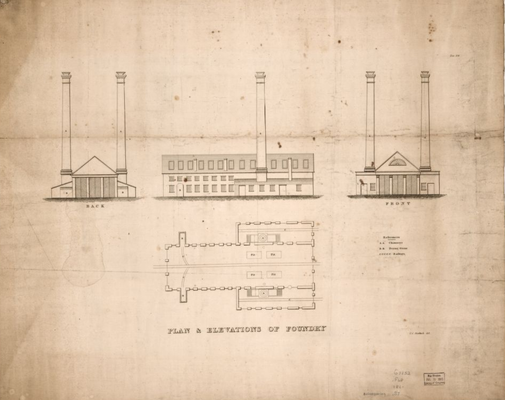

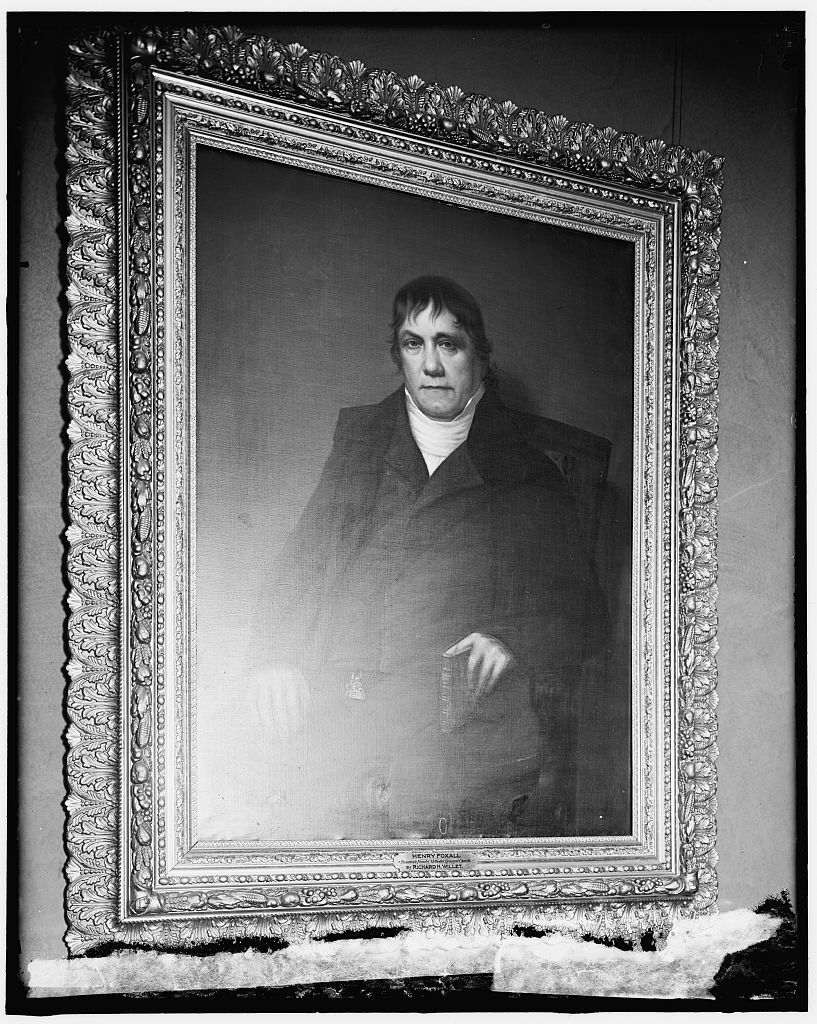

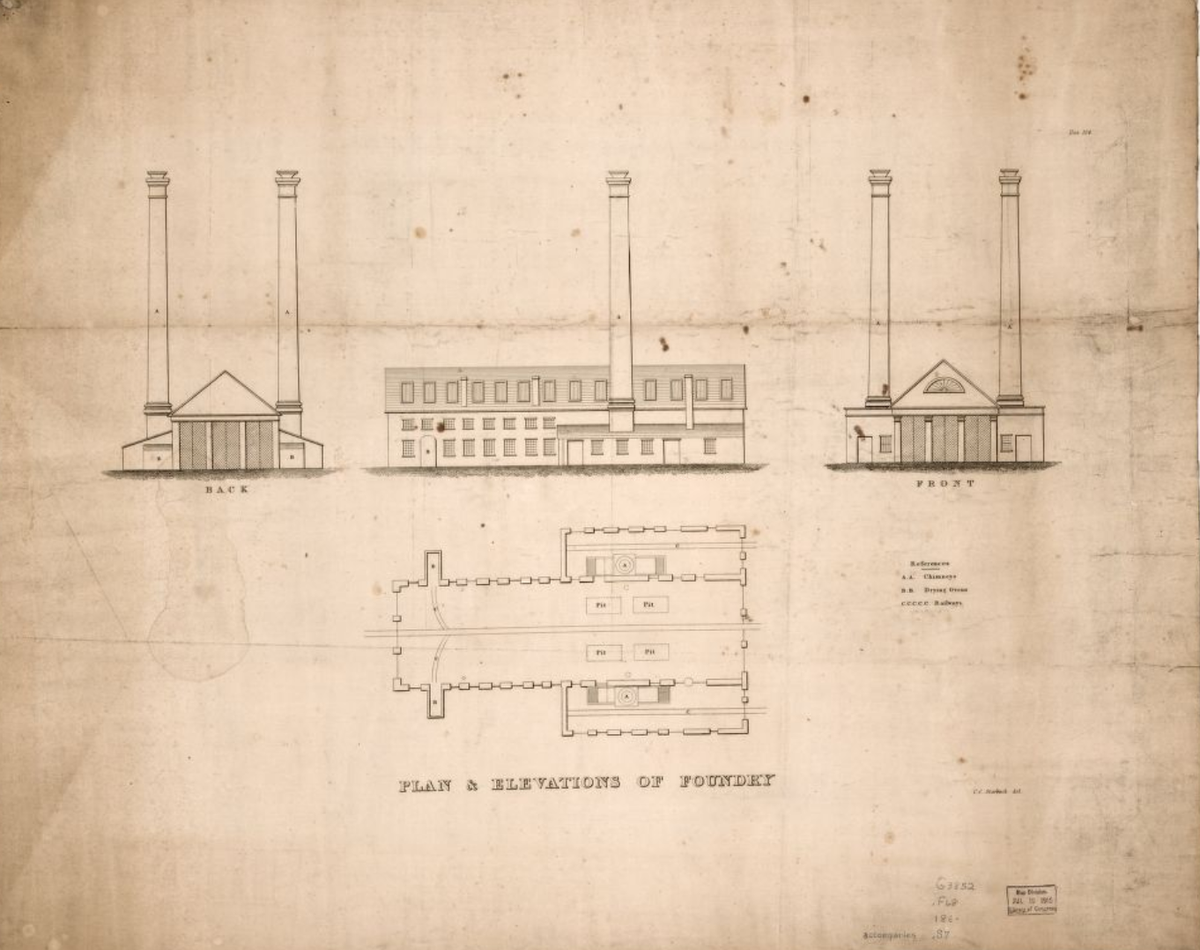

The Columbian Foundry opened in 1800, when Englishman Henry Foxall arrived in the Federal City with an armload of munitions orders (likely aided by his friend Thomas Jefferson). The riverbank site was perfect for the new enterprise: pig iron imports arrived via Potomac wharves (later, the C&O Canal), power was furnished by water wheels on the Foundry Branch Creek, and finished guns were tested at a two-acre firing range on the present site of Foxhall Road.

The Columbian Foundry was a significant industrial resource for the nascent country. Foxall pumped out an estimated 10,000 cannons in the early 1800s, and the forges produced all manner of artillery. Using the latest techniques from England, Foxall drilled his guns from solid iron tubes using special precision machines. Superior weaponry from the Foundry is credited with delivering Oliver Perry’s victory over the British at the Battle of Lake Erie in 1813.

But the Foundry was very nearly destroyed a year later as British Redcoats torching the capitol targeted the expat arms manufacturer. An unseasonal August downpour saved the plant and Foxall, counting it an act of Divine intervention, sold the company off. He used the money to build Foundry Methodist Church, where his portrait still hangs to this day.

The Columbian Foundry continued for decades under the guidance of local businessman John Mason, but, as the Washington Historical Society notes, by the time of his death in 1849, “the Columbian Foundry was reduced to making little other than shells and cannon balls to be fired from the guns made at other foundries.”

Consensus is out on exactly which sections of the walls date to Foxall’s period. An exhaustive but dated Historical Society report from 1908 tells us that the foundry was, “partly housed in and hidden by a huge frame structure used some years ago as an ice-house by the Independent Ice Company.” National Park Service archeologist Justin Ebersole thinks most of the ruins visible today are, “that of the ice house and not the foundry. I'm certain that something remains of the foundry (I've seen a slag pile out there), but a concerted effort has not been taken to fully survey the area.”

What is clear is that Foxall’s spot on the Potomac was drastically altered in 1911 as the B&O railroad ran a spur between the river line and canal. With the railway long since replaced with a bike path, another historical circle of redevelopment has closed its circuit, and cyclists are free to look on the ruins in wonder.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

Starting in Georgetown you can find the ruins half a mile up the Capital Crescent trail, on your right hand side, next to the Foundry Branch culvert.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

October 17, 2017