Honoring the Thousands of Forgotten Souls Buried Beneath San Francisco

Experts estimate some 50,000 people are buried beneath the sprawling metropolis.

Thousands pass through the United Nations Plaza, a pedestrian mall adjacent to San Francisco’s commanding Beaux-Arts City Hall, each day. It’s a gateway to the city’s Civic Center and an access point for multiple forms of public transportation. For over 40 years, it even hosted one of the city’s largest farmers markets.

But beneath the paving stones lies a secret. Beginning in 1850, when this now central corridor was then at the city’s westernmost edge, an estimated 7,000 to 9,000 bodies were buried in the sandy soil here. With the city’s population heaving with Gold Rush-driven newcomers, it took just eight years to fill the cemetery known as Yerba Buena.

After Yerba Buena Cemetery stopped accepting new residents in 1858, the cemetery quickly fell into disuse. Body harvesting (for medical and scientific studies) and vandalism plagued its gravesites and left local residents disgusted by the site’s neglected state. In 1868, San Francisco finally earmarked $10,000 for the disinterment and reburial of the bodies farther from town.

The sum, however, was only a fraction of what they needed.

When the city had moved everyone the budget would allow for, officials quietly sealed the rest of the graves beneath the growing city. To this day, no one knows exactly how many people are buried under U.N. Plaza; few San Franciscans even know there are any bodies at all.

That’s because, according to the city’s official narrative, these graves don’t exist. The city claims San Francisco removed the graves from all but two small cemeteries within the city limits and reburied them in the town of Colma beginning in 1930. In Colma’s expansive, green-lined necropolis 15 miles to the south of San Francisco, the dead still outnumber the living 1,000 to one.

But the official narrative is wrong. Thousands of San Francisco’s deceased still lie not just under U.N. Plaza, but under the city’s main library and the Asian Art Museum downtown. They are still buried under the grassy quad at the University of San Francisco in the residential Inner Richmond neighborhood and beneath the hipster hangout Dolores Park in the Mission District on the city’s south side.

Journalist Beth Winegarner, author of the new book San Francisco’s Forgotten Cemeteries: A Buried History, estimates that there are more than 50,000 forgotten graves beneath the sprawling city. There are no memorials that mark the places of their eternal rest, and few know they’re there except when major construction projects dig up forgotten coffins. “Over and over again, the city kept forgetting where it put its dead,” Winegarner says.

It was those most vulnerable in life—Native Americans, immigrants, and impoverished and itinerant workers without family support networks—who were most vulnerable to being abandoned after death.

With no fear of political or financial retribution, the city simply pretended that nothing of the burial grounds remained, a practice particularly insidious for members of historically marginalized communities with a strong reverence for their ancestors including the Ohlone and Miwok Tribes and the immigrant Chinese community. With no bodies to speak of, it wasn’t difficult for the living to forget the role these individuals played in shaping the city’s history.

“We don’t have the opportunity to visit those spaces and get a sense of the people who were here before us, the people who made the city what it is,” says Winegarner. Still today, “we don’t have burial grounds for the people we’re losing now, people who died in the AIDS crisis couldn’t be buried here, in the Covid epidemic, in the Jonestown Massacre [whose victims had close ties to San Francisco],” she says.

When the memories of a city’s past are erased, its present and future become unmoored. “San Francisco’s been repeating itself over and over again since its creation,” says Winegarner.

Of the thousands of graves still hidden in plain sight in San Francisco, one of the largest was once the segregated Chinese burial ground of the former City Cemetery, where an estimated 10,000 Chinese immigrants and Chinese-Americans were initially buried, and at least 3,700 unmarked graves remain.

Early on, most Chinese immigrants wanted their remains to be returned to China after death but by the time the City Cemetery was operating in the late 1800s, many no longer wanted to be returned to a distant ancestral homeland, says Larry Yee, president of the Hop Wo Company, part of the historical Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, a social and political society that provided protection and resources for early Chinatown immigrants.

At City Cemetery, descendants of the deceased would have come at least once a year to pay their respects. “They built a shrine—across the top it says Kong Chow Travelers Burial Site—and in there used to be an altar to put offerings to the ancestors,” says Yee.

In China, burial grounds are sacred spaces that keep the memory of loved ones alive. So when the Chinese community was told that the grave sites had to be moved as part of San Francisco’s 20th-century mass disinterment, many were horrified.

Traditionally, says Yee, Chinese custom forbids disrupting the spirits of the dead once someone is buried. Around 60% of the graves were moved to Colma nonetheless; it’s unclear whether San Francisco’s Chinese community knew that those ancestors left behind would lay for an eternity under the city’s first public golf course, Lincoln Park.

Although the Kong Chow shrine remains, until recently, no one, least of all the park’s golfers, knew there were graves six feet below its manicured lawns.

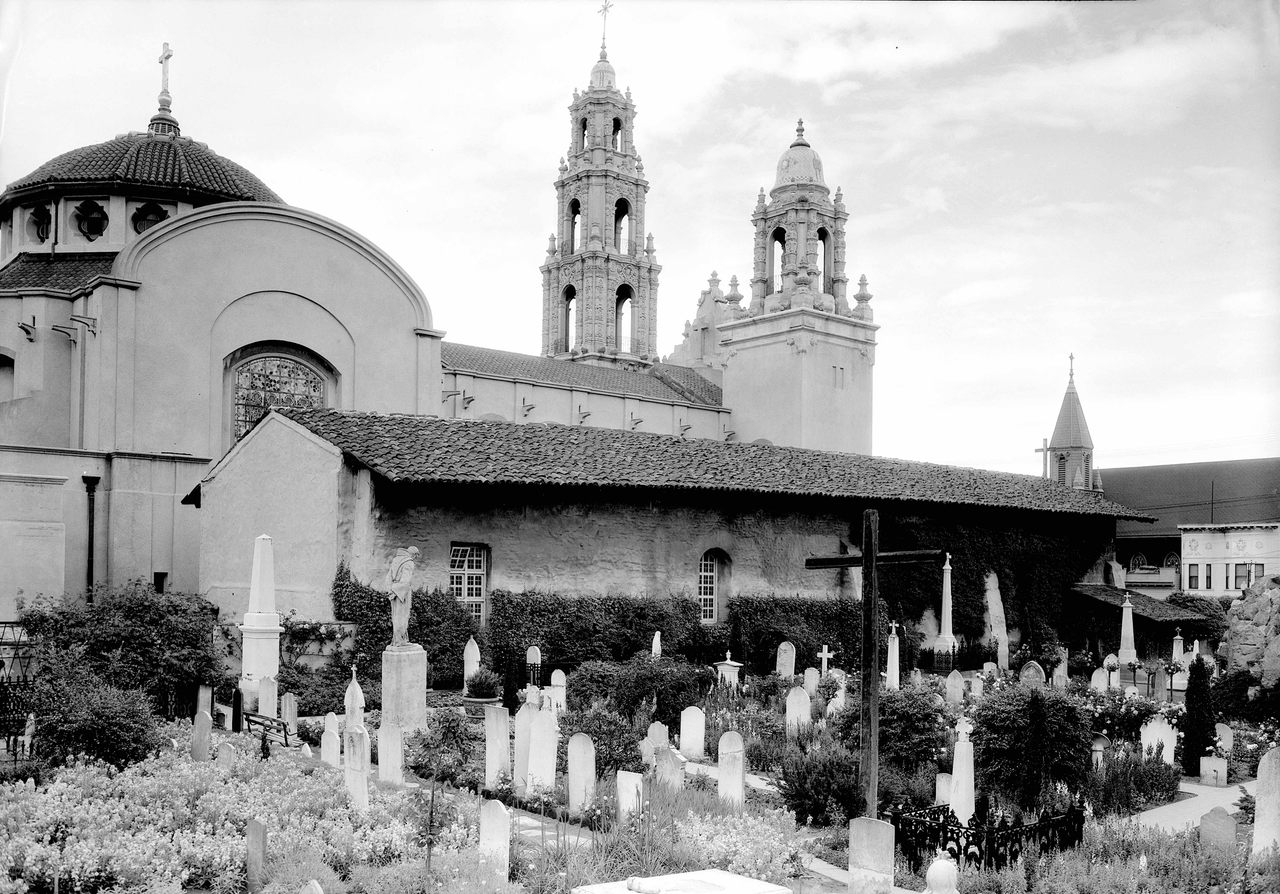

The residents of San Francisco’s early Chinese cemeteries aren’t the only deceased the city abandoned as it developed. At its oldest burial ground at Mission Dolores—one of only two historic burial grounds the city did not purge in the 1930s—the gravesites marked in its tiny yard are just a small portion of those who are still buried there.

Thousands of primarily Native American ancestors were sealed beneath asphalt to make room for a widened street and a neighboring school in the 19th century. For decades, children there have been unaware that at recess, they play on the graves of the city’s first residents.

“The Mission was built by Indian people,” Old Mission curator Andrew Galvan and deacon Vicente Cervantes, both members of the Ohlone community, co-wrote in a recent essay, and it’s likely that the vast majority of those forced to live and work at the mission are still buried there. “We’re determined to tell that neglected history.”

The pair is at work on a project to digitally project all 5,700 names of the Native American neophytes recorded in the Mission’s death registers between 1782 and 1850 onto its white-washed walls. They will use only the Native names of the deceased, not the Christian ones they were forced to adopt.

“Symbolically projecting those once banned names onto this institution of colonization sends a powerful message that traditional, Native names matter and that they are not forgotten,” they concluded.

At the former site of the City Cemetery, the Chinese community has also mobilized to ensure that those who came before are not now, and will never be, forgotten. For the last two years, Chung Yeung, a festival that honors and provides offerings for the ancestors, was celebrated at the Kong Chow shrine at the Lincoln Park Golf Course, likely for the first time in over a hundred years.

In 2022, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors went one step further: They made the site a historic landmark, recognizing the immigrant and indigent people who were left behind in the great move to Colma.

This October, Chung Yeung will take place at the Kong Chow shrine again. Although the modern Chinese-American community in San Francisco comes from a different region than the city’s first Chinese immigrants, its members still recognize the sacrifices and hardships of those who came before, says Yee. Today’s Chinese community is “proud to reconnect with the history that is here,” he says.

Having finally earned the recognition for which they’ve so long waited, the thousands of San Francisco pioneers buried among the golf course’s windswept Monterey cypress trees, a view of the Golden Gate Bridge at their backs, can finally rest in peace. The rest of the city’s 50,000 forgotten deceased are still waiting.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook