Where Did the 12 Days of Christmas Come From?

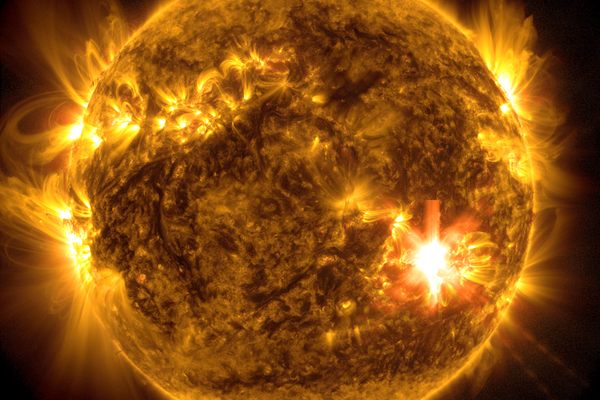

The answer is the Moon.

Atlas Obscura’s Wondersky columnist Rebecca Boyle is an award-winning science journalist and author of the upcoming Our Moon: How Earth’s Celestial Companion Transformed the Planet, Guided Evolution, and Made Us Who We Are (January 2024, Random House). She regularly shares the stories and secrets of our wondrous night sky.

“On the first day of Christmas, my true love gave to me a partridge in a pear tree.” You probably know the tune by heart, if not the full list of gifts and their attendant lyrics. Setting aside the eyebrow-raising number of birds-as-presents, the song “The Twelve Days of Christmas” evokes a tradition of celebrating for several days around the actual day of Christmas.

Many people, including those who celebrate Christmas as a secular, commercial winter holiday, consider the 12 days before Dec. 25 as the primary period of festivities. Those who follow Western Christian traditions count the 12 days of Christmas as the period after Advent ends on Dec. 24, lasting until the Feast of the Epiphany, the traditional date marking the baptism of Jesus, on Jan. 6. (Eastern Orthodox Christians celebrate Christmas Eve that day; in their tradition, the 12 days conclude on Jan. 19.)

Whether you mark them before or after Christmas, why are there 12? Why in the dead of winter, and why so many birds? The answer is the Moon.

To many ancient cultures, the Moon signaled the start of a new unit of time, or month. For some cultures it was the arrival of a full Moon while, for many others, it was the brand-new crescent Moon that marked the start of the next cycle. Most ancient cultures also paid attention to the lowest point of the solar year, the winter solstice, which happens this year in the Northern Hemisphere on Dec. 21.

To understand the relationship between these cyclical events, we have to talk about geometry for a second.

Over the course of a year, because our planet is tilted on its axis, the sun’s course across the sky changes. In the Northern Hemisphere, where I am, the sun is low in the sky now. Along the Tropic of Capricorn, which slices through South America, Southern Africa, and Australia, the sun is high overhead, perpendicular to Earth’s surface, and near the center, or “top” of the sky, which we call the zenith. By late June of next year, the so-called subsolar point—where the sun’s rays are perpendicular to the planet’s surface—is north of the equator, and those of us in northern latitudes will see the sun high overhead. In the American West where I live, people sometimes still call this “high noon.”

At mid-latitudes—including most of North America and Eurasia—the easiest markers of the sun’s passage are the summer and winter solstices. The solstice is when we can observe the changeable path the sun takes across the sky, as it moves east to west, pause for a day and then begin reversing direction: After the winter solstice, the sun appears to rise and set a little further to the north each day.

In equatorial areas, the solstice is less obvious, so people would trace the overhead passage of the sun across the zenith, when you would experience a shadowless day. All over the world, between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, humans built stone and wood monuments that acted as celestial alignments that mark this event.

The upshot is that almost no matter where you are on Earth, the sun’s changing course gives us shorter or longer days. Before the modern era of artificial lights, it was easy to notice this transition over time—and the solstice became an obvious way to mark a solar year’s completion. Many cultures used the winter solstice to do this, in part because it heralds the shortest day and the longest night of the year. After the winter solstice, we can look forward to more sunlight and warmth, and with it renewal and new growth. The sun has completed its annual journey through Earth’s sky, and a new year can begin. This takes 365.25 days.

If you pay attention to both the Moon and the Sun, you will notice about 12 complete lunar cycles in the time between winter solstices. But 12 Moons takes up only 354 days. This discrepancy means that the lunar year is 11 days—or 12 nights—shorter than the solar year. To keep them synchronized, people needed to add 12 days to the lunar calendar. The 12 days of Christmas are just a holdover from that ancient calendar correction.

The celebration of Christmas taking place around the solstice is also no coincidence. Long before anyone celebrated the birth of a man called Jesus of Nazareth, people in northern latitudes celebrated light and new life in the long, dark days of winter, often with great feasts borne of practicality. As feed and fodder stores dwindled and keeping livestock alive became more difficult, people often slaughtered some of the animals; they also relied more on hunting, including game birds. Swimming swans, calling birds, French hens, turtle doves, geese a’laying, partridges—these fowl could all make it to the menu. Wine, beer, and spirits—made with fruits and grains harvested in summer or early autumn and then fermented—were also, at last, ready to drink. In the fourth century, Pope Julius I became the first pope to mark December 25 as the feast day of Christmas, perhaps because church leaders knew the holiday would be easier to adopt if it fit into existing—and ancient—celebratory traditions.

Though the feast day of Christmas has endured, the 12 days of Christmas as a calendar correction tool have largely vanished. Another Julius—Caesar, dictator of Rome—divorced the Moon from the Sun and instituted a purely solar calendar in 46 B.C. Today, the revised Julian calendar, which has no need for adding 12 days to the calendar year, has been widely adopted. (Many religious, traditional, and cultural calendars still use the lunar year, or a combined lunisolar year, to mark certain events and feasts, but the civil calendar does not.)

Still, we can celebrate the 12 days of Christmas as a time of light amid darkness, a time of togetherness and peace, a time of feasts and celebrations, and a time of reflection.

However you make meaning during these 12 days, whether you count them before or after the arrival of Santa, Jesus, Krampus, or whatever else you believe, remember that they also connect you to the Moon. They connect you to the Sun. They connect the celestial bodies to one another. And they connect you to all people who have lived before you, who used and celebrated the two lights in the sky long before any other traditions, secular or otherwise.

Is there something you’d like to know about our brilliant night sky? Share your stargazing questions with us and you may see them answered in a future Wondersky column!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook