Why Does America Have So Many Towns With Classical Names?

There are nearly 100 named “Troy.”

“Like Cincinnatus, I am returning to my plow,” said Boris Johnson in his farewell speech, on Monday, September 5, 2022, in front of 10 Downing Street. The former British Prime Minister, who studied the classics at Oxford, likes to pepper his speeches with references to Greco-Roman antiquity. This one was perhaps more significant than most.

A Story With a Twist

When called upon to repel the invasion of a neighboring tribe, Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus (ca. 520–430 B.C.) abandoned his plow and led the early Roman Republic to victory against the Aequi a mere 16 days later. And then, instead of clinging to power and privilege, he simply returned to his farm, thus becoming an emblem of selflessness and civic virtue. (Prior to Julius Caesar, it was common for the Roman Republic to appoint dictators temporarily to handle an emergency, after which the dictator relinquished power.)

However, the Cincinnatus story has a twist. Some sources say he regained dictatorial powers years later, this time to suppress an uprising of Rome’s lower classes. It had been hinted that Johnson, frustrated by the brevity of his time in office, aimed to return one day as prime minister. His use of the Cincinnatus story does nothing to dispel that rumor.

As the British journalists looking up that back story must have discovered, there’s not just Cincinnatus the person, but also Cincinnatus the place. Not to be confused with Cincinnati, the Ohio city with a metro population of 2.2 million, Cincinnatus is a town of around 1,000 souls in a part of upstate New York that Boris Johnson would appreciate: It’s ground zero for America’s love affair with classical place names.

Driving through this area is like leafing through a who’s who of antiquity, with town after town named after mythological and historical figures, from Greek (Hector, Homer, Solon) and Roman (Romulus, Scipio, Virgil) times.

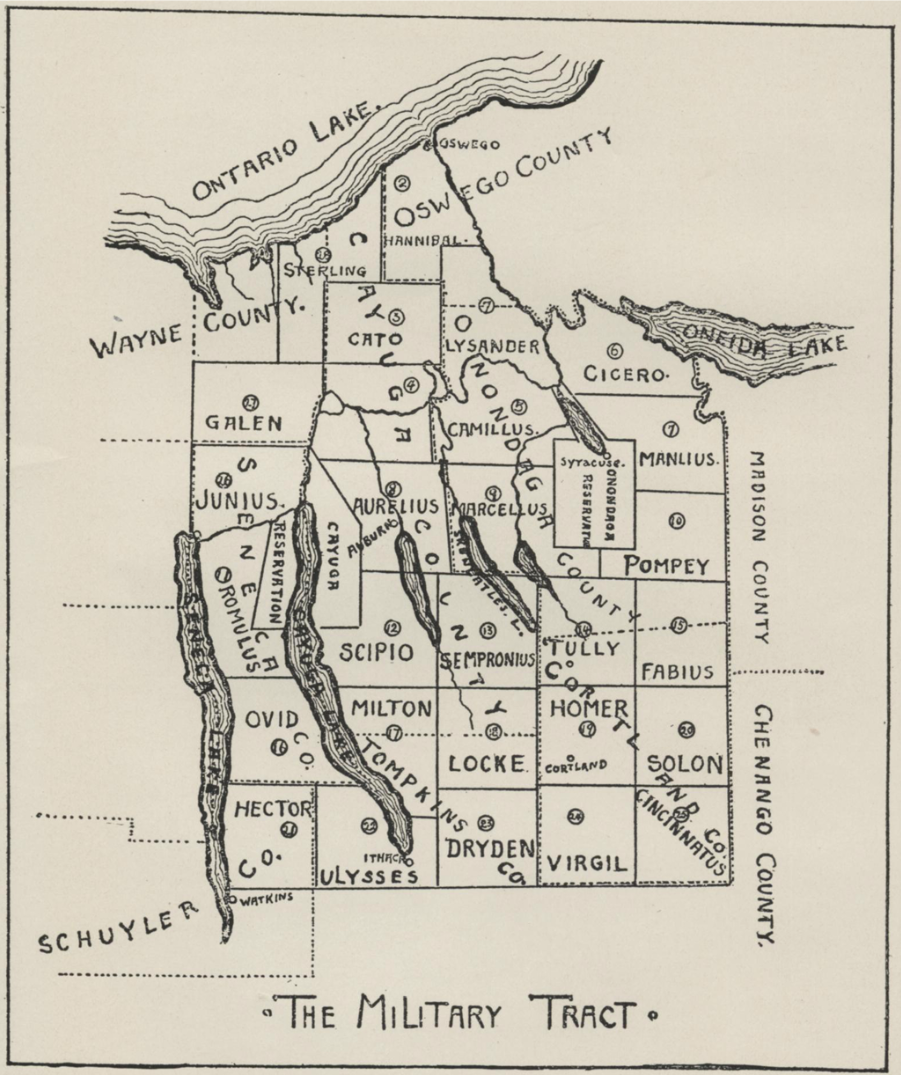

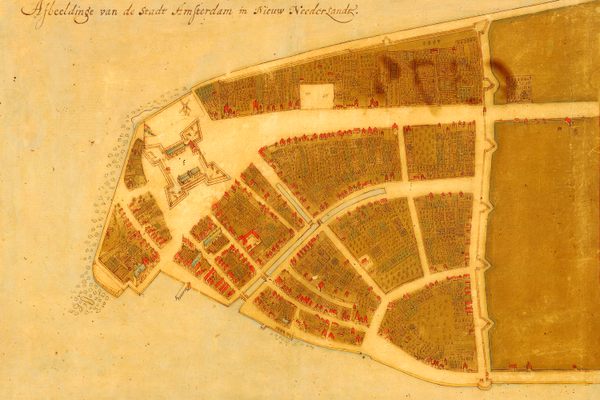

This part of New York State, which touches Lake Ontario* and includes some of the Finger Lakes, was once known as the Military Tract, an area of 60,000 acres set aside by the New York state legislature for settlement by veterans of the American Revolutionary War. Of the 28 towns in the Military Tract named by the Land Office in 1790 or soon thereafter, 24 had classical names.

A Renaissance of the Renaissance

At the time, both Europe and North America had a rekindling of interest in the classical era—a renaissance of the Renaissance, so to speak. But that neoclassicist revival gained an extra layer of meaning in the newly independent United States, wrote William Zelinsky in a 1967 article in Geographical Review:

[T]here was an abrupt crystallization of the classical idea in the young Republic’s newer settlements and the notion of a New Athens and a New Rome was becoming a lively one, supplementing the long immanent doctrine of a New Zion. The concurrent French Revolution, linking as it did the image of the classical world with republican principles, probably gave the new fad added impetus.

That’s how the Military Tract—developed soon after the Revolutionary War, and specifically for its veterans—turned into a hotbed of classical place names. The neoclassicist “fad” also influenced building styles. And so the Military Tract also became “the zone of maximum intensity for the early development of Greek Revival architecture and for the penetration of this style into vernacular buildings.”

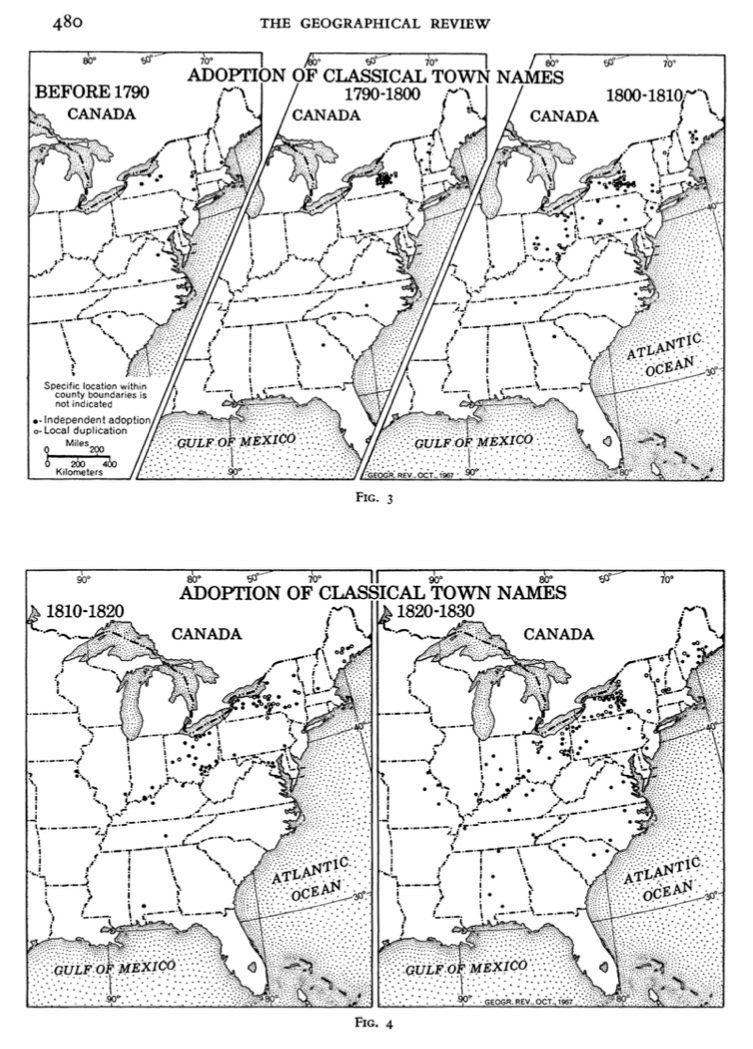

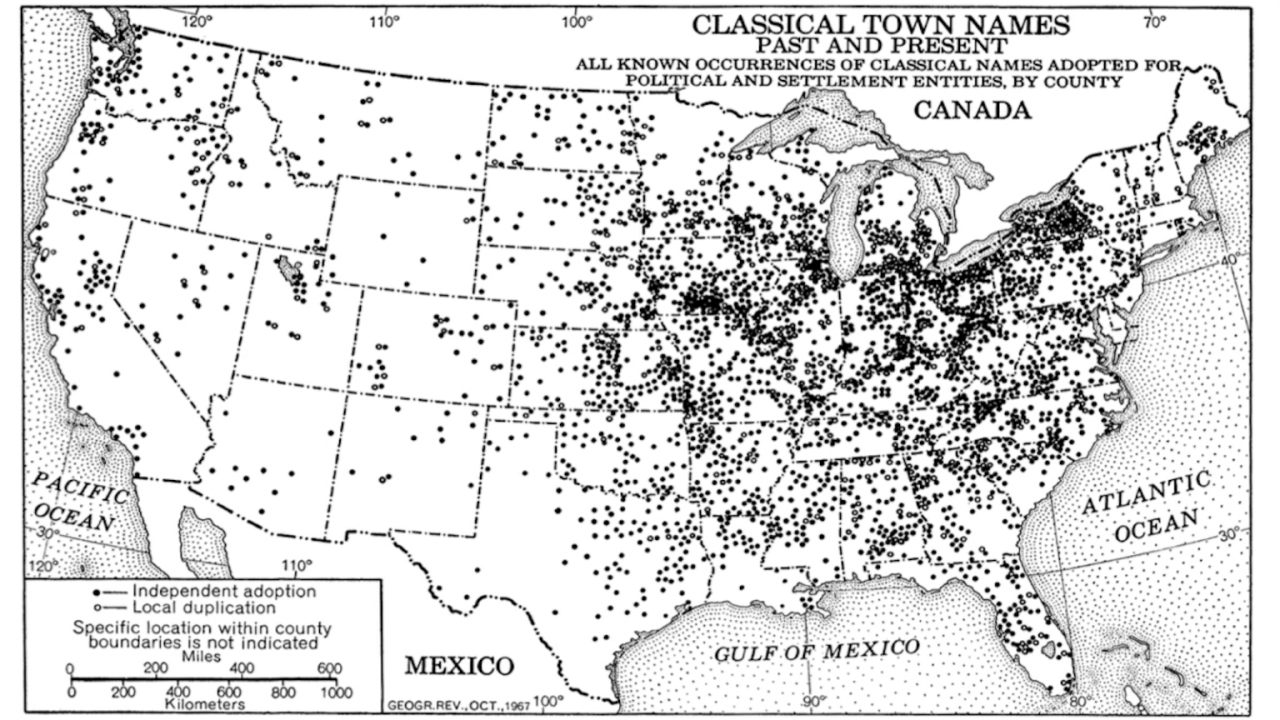

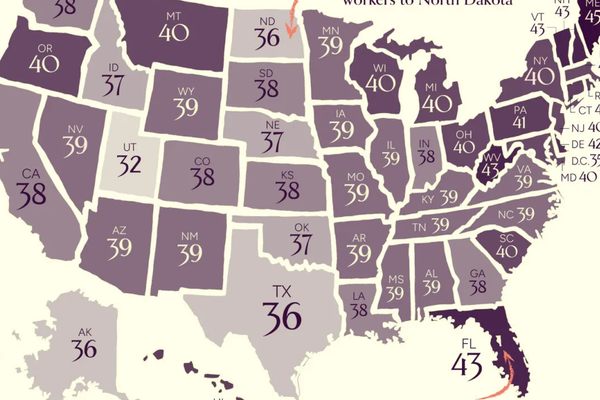

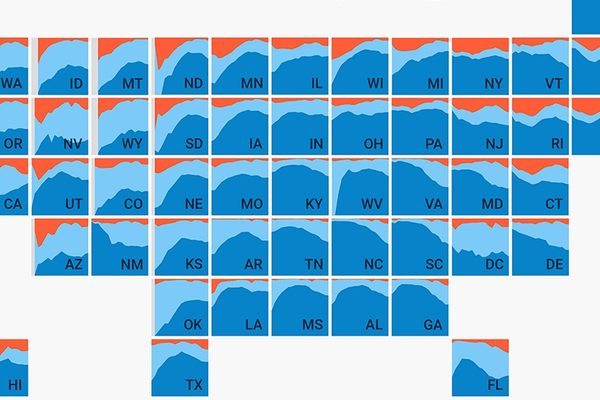

As the American frontier expanded, the classic style of naming towns and building houses spread from the Military Tract throughout the rest of the country. As these maps show, the spread was somewhat uneven.

America, Land of (Almost) 100 Troys

Some classical names turned out more popular than others. For example: Syracuse (in New York) only chose that name (in 1820) because Corinth was already taken. Listing the most popular localities with classical names, Zelinsky found that Troy, with 97 occurrences, was the most widely used place name. Here’s the entire top 10:

- Troy (97)

- Eureka (83.5)

- Anyplace ending in -polis or -ople (68.5)

- Etna (57)

- Antioch (56)

- Athens (54.5)

- Rome (54.5)

- Albion (51)

- Arcadia (50)

- Palmyra (49)

The list includes people and places from antiquity, but also Greek letters such as Alpha (39) and Omega (29). There are about a dozen Utopias in the United States, and half a dozen Coronas.

The 10 least popular place names on the list (each with just five occurrences) are Athen(i)a, Brutus, Cadmus, Caesar, Ephesus, Nestor, Pandora, Parnassus, Patmos, and Theta.

The United States is not the only settler country with the need to come up with names for thousands of new villages, towns, and cities. However, the wholesale adoption of Greek and Roman names for places is something particular to the United States, and repeated only on a much smaller scale in countries such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the countries of Latin America.

George Washington, America’s Cincinnatus

In the United States, the “classic fad” lasted from about 1790 to 1870. Out west, it would give rise to strange hybrid names, often deliberately contrived to sound both classical and Native American.

Itasca, for example, is made up of the last and first letters of veritas caput, Latin for “true source.” The name was made up in the 1830s by geographer Henry Schoolcraft for the lake from which springs the Mississippi River. The lake’s original Ojibwe name is Omashkoozo-zaaga’igan.

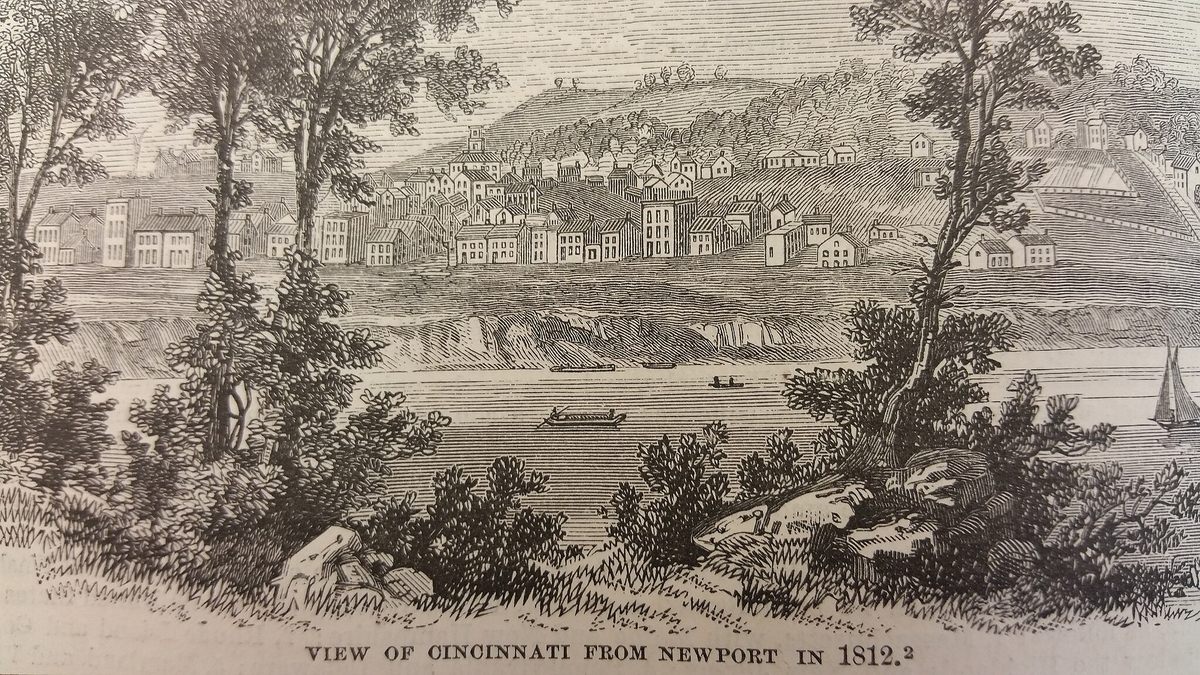

Cincinnati, by the way, was also named after that Roman hero who returned to his plow, but in a more indirect way. The settlement, originally known as Losantiville, was renamed after the Society of the Cincinnati, an association of veteran officers from the Revolutionary War. The link between Cincinnatus and the early American republic was exemplified by George Washington, who resisted calls to assume royal powers, and stepped down after two terms in office to return to Mount Vernon, his Virginia estate.

Many thanks to Bruce Hyman for pointing out this toponymical curiosity.

* Correction: This article originally stated that that part of New York touches Lake Erie, rather than Lake Ontario.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook