400 Years After Its First Apple Farm, Boston Remains an Urban Orchard

Urban canners and tree-planting groups are maintaining an heirloom tradition.

John Bunker normally searches for heirloom apple trees in the fields and forests of rural Maine, but on a trip to Boston, he stumbled upon one in an unexpected place: an ice-cream-parlor parking lot. An expert on American heirloom apples, particularly those of Maine, Bunker has been investigating, preserving, and growing nearly forgotten apple cultivars since he graduated college and immediately bought a parcel of Maine farmland in the 1970s.

“I could spend the rest of my life studying, tracking down, learning to identify, and preserving historic apples from Maine, and I’d never run out of something to do,” says Bunker, who grows the rare apple trees at his family-run Super Chilly Farm, and sells them through Fedco Seed Cooperative.

The parking-lot apple tree was a rare find for Bunker, who mostly searches the woods and fields of sleepy New England towns. Apple trees can stand watch in quiet forest hollows for two centuries, remembered only by neighborhood elders. But these days, Bunker says, old urban apple trees “are mostly gone.” So Bunker got into the habit of visiting the ice-cream-parlor tree. “One year, when I stopped by—oops, it had been cut down,” he says.

The parable of the parking-lot apple tree, which survived decades of urban development before finally succumbing to the saw, embodies the trajectory of New England’s heirloom fruits as a whole.

Boston’s reputation as an epicenter for heirloom fruit dates back to 1623. That was the year European settlers planted their first apple orchard on the land of the Massachusett tribe, in what is now Boston’s posh Beacon Hill neighborhood. There were apple relatives in the New World before European colonization, but the ancestors of the fruits we eat today originated in Central Asia, entered Europe through the Silk Road, and were brought to North America by Europeans. Settlers developed dozens of new fruit cultivars, but apples were the most important, offering colonists cider and sustenance through the brutal New England winters.

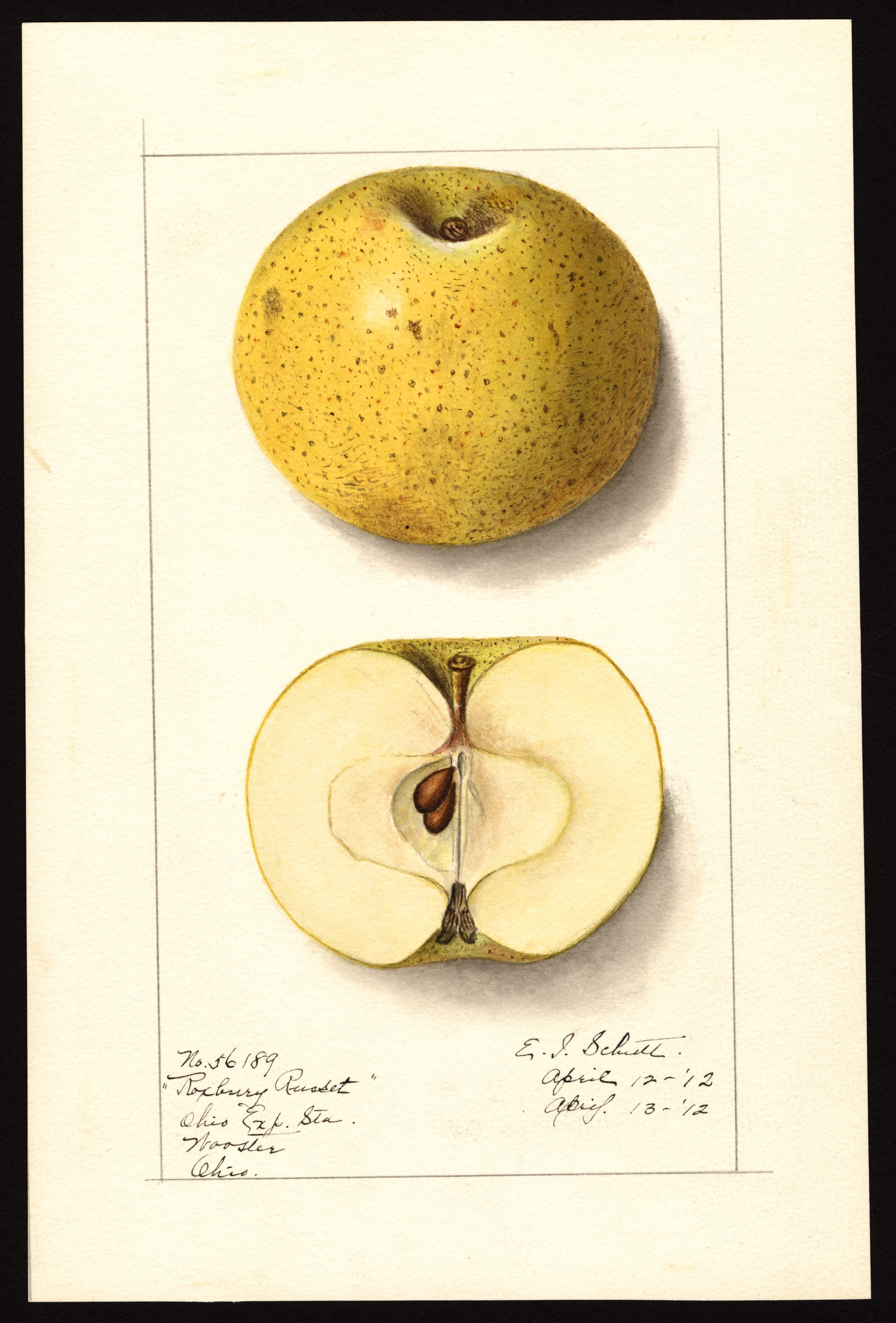

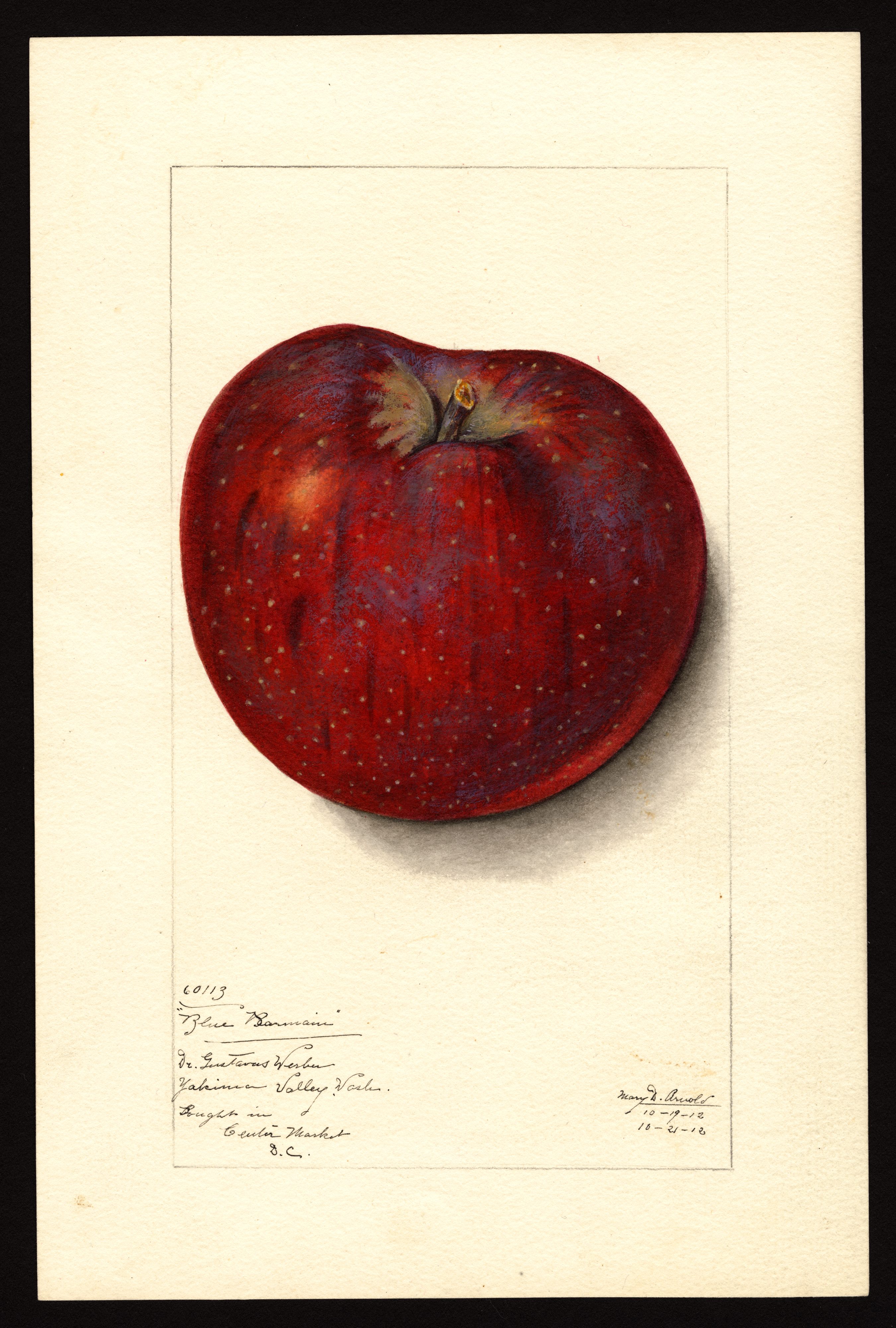

Settlers in Boston developed several unique apple varieties, from the sandpaper-skinned, acid-fleshed Roxbury Russet (the first American colonial apple, developed in the mid-1600s) to the bluish-maroon, melon-musky Blue Pearmain (developed in the late 1700s).

The legacy of these orchards remains inscribed in Boston’s landscape, in place markers like the giant bronze pear statue in Dorchester’s Everett Square, and in residential names, like Roxbury’s Orchard Park. By the mid 1900s, however, the heirlooms had been mostly decimated by the encroaching city, and by the rise of industrial monoculture, which focused on intensive farming of fewer, supermarket-optimized varieties, which displayed qualities like shiny red skin, virtual indestructibility, and often-bland taste. This near-erasure of centuries of agricultural history inspired Bunker, who came of age during the budding environmental and anti-capitalist movements of the 1970s, to begin his campaign to save New England heirlooms.

In the past decade, Boston community groups, such as the Boston Tree Party and the League of Urban Canners, have found creative ways to bring the city’s history of heirloom orchards alive. Inspired by activists like Bunker, the community-garden movement, and the rising popularity of urban foraging, they’ve planted new urban fruit trees, mapped hundreds of old ones, and created community by re-imagining one of colonial Boston’s first food traditions: picking and processing fruit.

One such re-imagining began in 2011, when Lisa Gross was a Masters of Fine Arts candidate in search of a food- and community-themed thesis project at The School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University. Gross, who has previously worked as a consultant for Gastro Obscura, had been involved in neighborhood homesteading projects in Cambridge, Massachusetts, for several years, sharing skills like canning and raised-bed backyard gardening at community meetups.

Gross turned to homesteading “out of this desire to reconnect to the earth, to our bodies, to how things are made, to what products are grown,” she says. For her thesis project, she wanted to turn these workshops into a more concrete and lasting community intervention. She also wanted to challenge the whiteness of some urban homesteading spaces by connecting with diverse community groups across the city, in recognition of the people-of-color-led community-garden movement that had set a precedent for neighborhood agriculture. Research into Boston’s agricultural history led her to a moment of revelation: Why not grow a public apple orchard?

Gross conceptualized a neighborhood-based project that would encourage collaboration and diversity by providing community groups with pairs of cross-pollinating apple trees. They would plant these pairs in community spaces across the city, in the hopes that the trees would become gathering spots and sources of education, celebration, and sustenance. “I thought that was this incredible metaphor about difference or cross pollination to create social fruits or civic fruits,” Gross says. At the time, the Tea Party was using both Revolutionary War imagery and, often, racist stereotypes to further a conservative agenda. Gross’s name for the project playfully riffed on the Tea Party’s historical reference to honor a more diverse and inclusive vision: The Boston Tree Party.

From 2011 to 2013, 47 participating groups, including public schools, youth programs, and community centers, received a kit that contained a pair of heirloom apple saplings, such as Baldwin and Roxbury Russet cultivars; compost and mulch; and a guide from Bunker, dubbed the project’s “Official Pomologist.” The project kicked off with tree-planting parties and barbecues, and it connected tree-planting “delegations” with continued resources for orchard care. For Gross, fruit trees were a way for communities to inject “beauty and pleasure and abundance” into collective spaces.

Other Boston residents have opted not to plant new fruit trees, but to seek them out in expected places. For about five years now, Matthew Schreiner, a programmer who lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has spent early summer scouring his neighborhood for juicy, shiny sour cherries, which are largely unavailable at grocery stores due to their delicacy and fleeting season. Schreiner is part of the League of Urban Canners, a loose collective of urban fruit harvesters based in the Greater Boston area. The group formed in 2011, when members of the Somerville Yogurt Making Coop began asking neighbors for permission to collect and can produce from their fruit trees.

Since then, the collective has compiled a database of around 300 fruit trees hidden in plain sight in public spaces, or tucked away in neighbors’ backyards. They’ve obtained owners’ permission to harvest fruits from up to 100 of these trees, including peaches, pears, cherries, berries, and, of course, apples. Schreiner estimates many of the trees are 50 to 70 years old, planted by less-elite Cambridge and Somerville residents who practiced Victory Garden-style thrift but, for the most part, no longer live in those homes. Many of the fruit trees were neglected by their owners until League members began knocking on doors. In exchange for letting the League harvest their trees, owners could receive a cut of the canned harvest. “At a certain point as the organization became more known,” says Schreiner, “people would call us looking for their tree to be harvested.”

In the earlier days, the collective met for harvest festivals, canned produce together in a local church kitchen, and collectively pressed apples on a local farm’s cider press. Homesteading had its hijinks: During one cider-making session at a neighbor’s house, Schreiner and friends dumped the leftover apple scraps in their host’s hen pen. The birds enjoyed the apples for a while, says Schreiner, “But then they started getting drunk.”

These days, members of the cooperative operate more autonomously, collecting and preserving fruits from local trees with which they have established a relationship. That’s what Schreiner and his friends do during sour cherry, peach, plum, and mulberry season, as they drag a homemade wagon, bearing the 10-foot ladder Schreiner is known for, to collect their favorite fruits. The mulberries ripen purple, staining the sidewalk in early June; the sour cherries peek maroon from high branches in early July, promising a sweet-sour pucker; and the peaches blush into melty, taut-skinned sweetness toward midsummer. Schreiner cans and dries his haul, collecting enough to last him until midwinter.

Meanwhile, Schreiner says, some community members continue to spread a DIY spirit through “guerilla projects” meant to make the urban space greener and more amenable to food production: planting vegetable gardens in neglected medians, or grafting edible fruit branches onto ornamental, non-fruit-bearing trees.

The coronavirus pandemic inspired many Americans to increasingly adopt gardening and community-based food distribution, and these “guerilla” attempts to democratize food production—even at the level of the city block—are imaginative expressions of an aspiration for more public-spirited cities. For Gross, community fruit trees are inherently democratic. “It just feels so magical that there’s an abundance of free fruit just ready to be picked,” she says. Orchards also remind us of what we have learned from the past, adds Bunker, and what we owe to the future. “This was a gift given to me by people who never knew me, who never knew that I would be. They left these legacies.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook