The Library of Congress Has an Incredible Collection of Early Baseball Cards

There’s a lot of history in these collectibles.

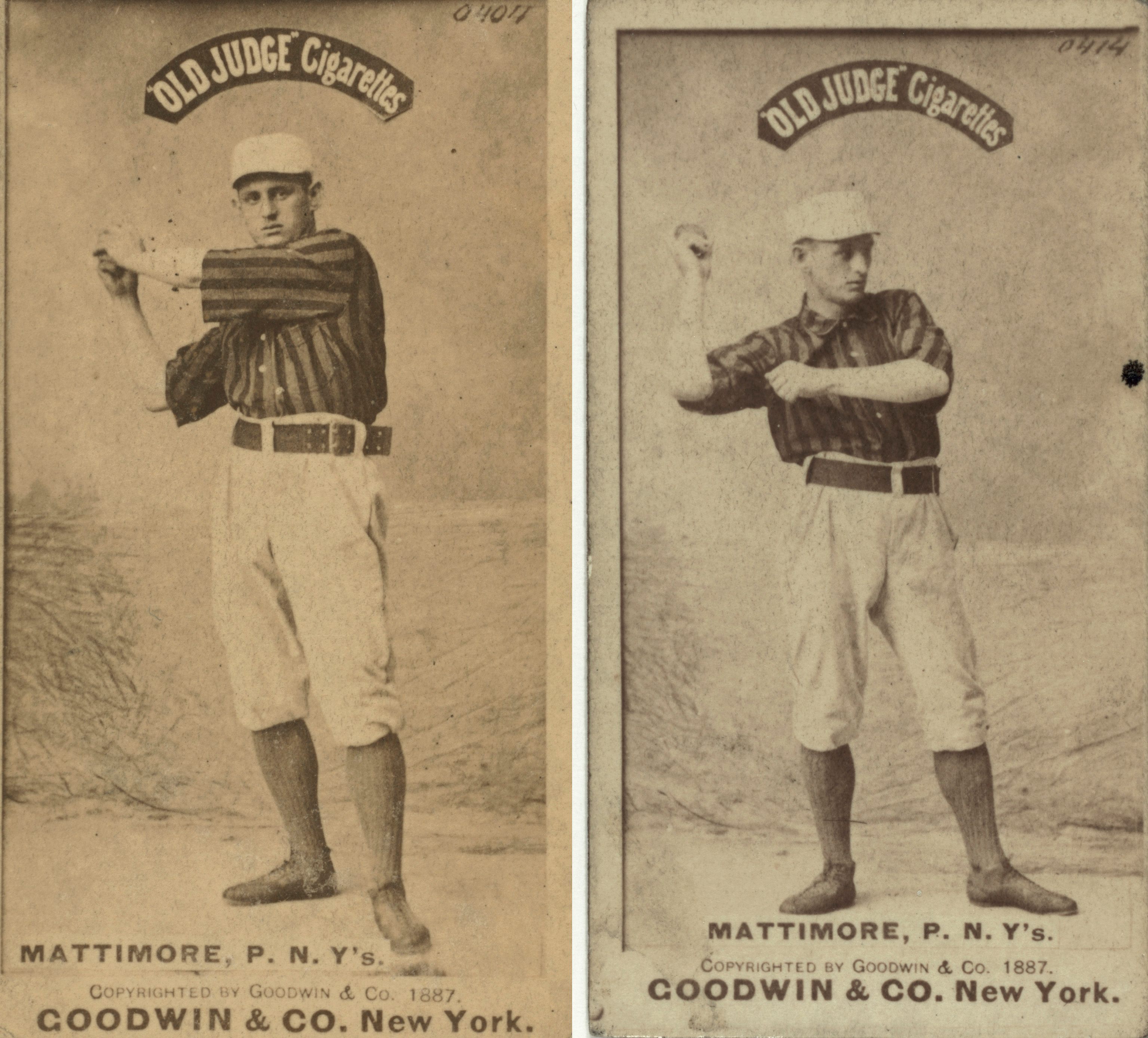

By any objective standard, Mike Mattimore was a middling professional baseball player. Born three years before the American Civil War, the pitcher-turned-outfielder played parts of four major league seasons between 1887 and 1890. After his final two campaigns with the Kansas City Cowboys and the Brooklyn Gladiators, he finished his career with 26 wins and 27 losses—a respectable but eminently forgettable record.

And yet, Mattimore isn’t forgotten. In 1887, Old Judge, one of the era’s most popular cigarette brands, included the pitcher in its extensive set of insert cards. As such, nearly 90 years after his death, Mattimore remains forever young, captured on one of thousands of similar tobacco cards held in the Library of Congress’s Benjamin K. Edwards collection.

According to Peter Devereaux, author of Game Faces: Early Baseball Cards from the Library of Congress, the presence of men like Mattimore is what makes the Edwards collection “a true photographic document of 19th-century baseball.” The Old Judge cards, he says, along with thousands of others produced by competing cigarette brands, are “a prism through which we can glimpse the conflict, progress, and change that occurred in [baseball] as it made the transition from an amateur pursuit to the nation’s pastime.”

This transition, of course, was not without its ugliness. Like so many 19th-century relics, first-generation baseball cards tell a dichotomous story, one that pits the romantic rediscovery of long-forgotten ballplayers against the legacy of morally-bankrupt monopolies. “While they have an aura of pastoral charm,” Devereaux says, “they also belie the sport’s seedy urban underbelly of gambling, drinking, and violence, as well as James Buchanan Duke’s ruthless tobacco empire [which] explicitly directed its advertising to children.”

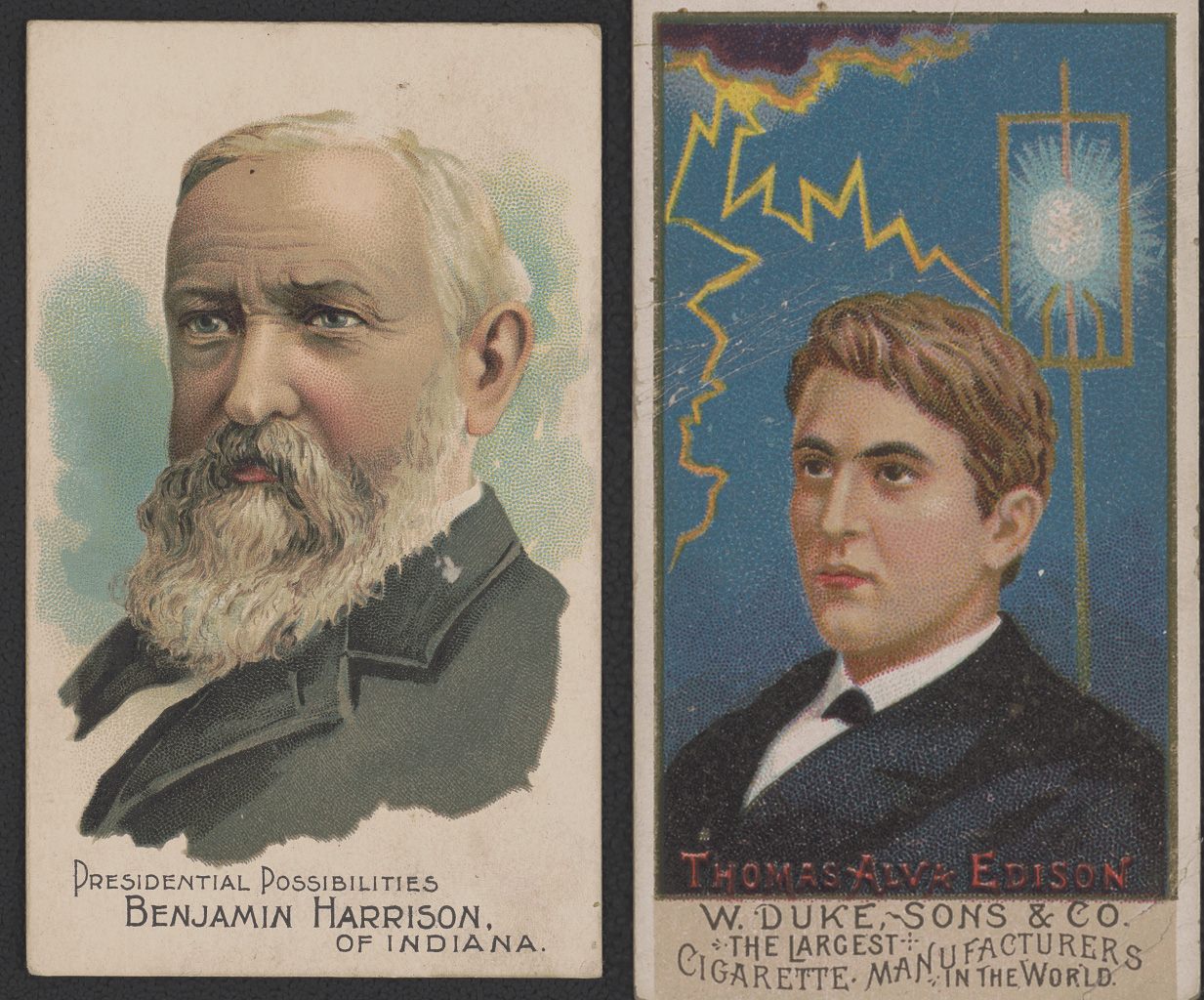

Indeed, the story of how ballplayers like Mattimore came to pose for tobacco cards provides rare insight into the early marriage of pop culture and mass consumerism. In 1881, James Bonsack, an American inventor, patented the first commercial cigarette roller. Duke, then head of W. Duke Sons & Company, embraced the machine, which instantly transformed the tobacco industry. Within a few years, competition intensified between his company and old rivals, most notably Allen & Ginter and Goodwin & Company.

“When the competition really got going,” Devereaux says, these companies looked to Europe, where tobacconists had already begun inserting cards into cigarette packs. “People would collect them, and this was a way to maintain brand loyalty.”

Most early tobacco cards depicted scantily clad women and prominent vaudeville actresses. Temperance advocates took aim at these cards, leaving Duke and his competitors in search of other options. Initially, they settled on categories ranging from Civil War generals to Native Americans to more innocuous subjects like flags, birds, and bridges. By 1886, they’d added baseball to their ever-expanding list.

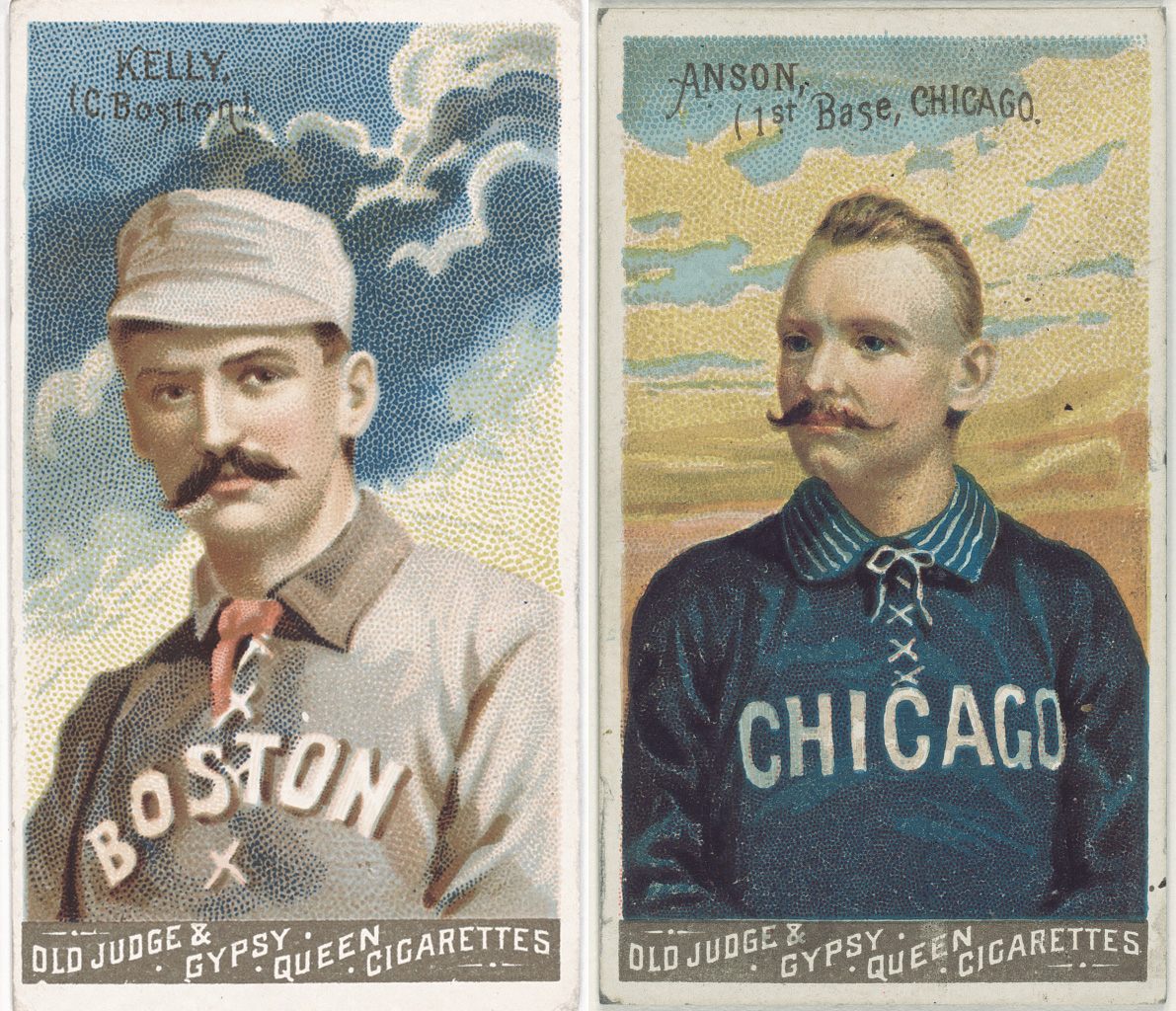

According to Devereaux, this decision paid immediate dividends not only for tobacco companies and the nascent major leagues, but also for the sport’s earliest fans. “You’re talking about a time when most newspapers and even periodicals didn’t really have photographs or illustrations,” he says. “For a lot of these people who were starting to follow the game, they didn’t know what King Kelly looked like, or Cap Anson, or any of the other early stars. I think the tobacco companies knew that.”

While most smokers took only a fleeting glance at these cards before throwing them away, contemporary magazine and newspaper articles do suggest a vibrant collecting culture existed. This included children. Indeed, in his award-winning monograph, The Cigarette Century, the historian Alan Brandt wrote that even at this early stage, tobacco companies understood what “would appeal to boys.” Card collecting, he wrote, “tapped into a powerful dynamic in the initiation of new smokers.”

“For years,” the Philadelphia Record reported in June 1890, “the small boy has been begging ‘won’t yer give me the picter!’” Illustrating this phenomenon with racist language common to the period, the anonymous author added that children of the day had assembled vast collections “of Indians painted in their most villainous dye, of sturdy athletes, base-ball players and what not—enough to set up a Louvre gallery of art in Smallboytown.”

Even here, however, the bottom line eventually took its toll. According to the same June 1890 article, the tobacco companies themselves had grown to lament cigarette cards. “The great question that agitated them,” the paper reported, “was how to stop this picture-giving business. As long as one gave, the rest had to do it too, in order to keep in the tide of popularity.”

Devereaux explains that there was a simple reason for this: Cigarette cards were expensive to produce. The Record estimated that major tobacco firms, combined, spent over two million dollars on them between 1885 and 1890. It isn’t surprising, then, that as soon as Duke enveloped his chief competitors within his newly formed American Tobacco Company, the cards disappeared. “He was able to corner the market,” Devereaux says. “And just like what was happening with Standard Oil and other big companies, he created a monopoly. The first thing he cut were these very expensive cards.”

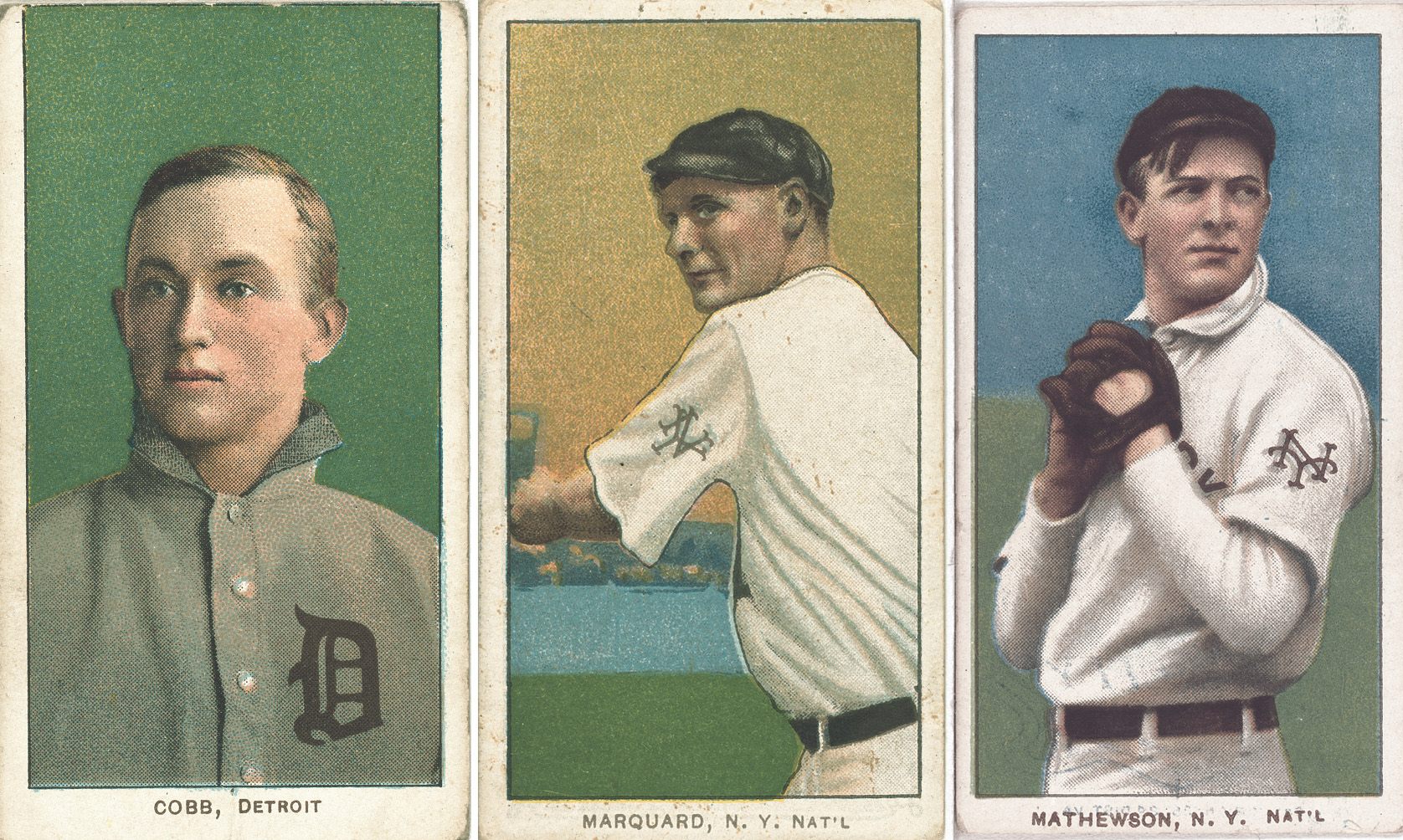

Baseball cards would not rebound until the Taft administration busted up Duke’s monopoly in the early 20th century. As for the thousands of cards released between 1887 and 1890, it’s a miracle so many survived. Those found in the Edwards collection are no exception.

Edwards, a Midwestern lumber mill owner, collected the cards throughout his youth. When he died in 1943, he bequeathed a collection of over 10,000 tobacco inserts, including over 2,100 baseball cards, to his daughter, who then regifted them to the poet Carl Sandburg in 1948. Sandburg in turn donated the cards to the Library of Congress in 1954.

The LOC has made all of Edwards’s baseball cards available online. By authoring Game Faces, Devereaux, who also writes for the LOC’s Publishing Office, says that he hopes to inspire those in possession of similar collections to follow suit. If so, the legacies of men like Mattimore, as well as the warts-and-all history of early baseball, might finally find new life online. “I’m hoping that this book will help start a digitization initiative,” he says. “Hopefully, we’ll get all the other cards from the other sports online, too.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook