Bodies in the Basement: The Forgotten Stolen Bones of America’s Medical Schools

Body snatching carved on a 19th-century tombstone (photograph by Stephencdickson/Wikimedia)

Body snatching carved on a 19th-century tombstone (photograph by Stephencdickson/Wikimedia)

Many people know about the resurrection men in the UK who robbed graves to sell corpses to medical schools, but few are aware that American medical schools also paid body snatchers to supply cadavers for their anatomy laboratories from the 18th to the 20th centuries. The skeletons in the closets of these respected institutions were sometimes hidden for decades until unsuspecting construction workers stumbled across bones in old wells or behind walls.

For much of the 19th century dissection was illegal in many parts of the United States, making it very difficult for medical students to learn human anatomy. So colleges had to rely on the discrete services of body snatchers who were sometimes slaves or employees of the schools. Grave robbing was even practiced by medical students and members of shadowy student organizations.

Medical College of Georgia

In the summer of 1989, a construction crew working in the basement of a building at the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta stumbled across thousands of human bones. Known as the Old Medical College Building, it was used as a lecture hall and laboratory space from 1835 until 1913.

Since dissection of human cadavers was illegal in Georgia until 1887, acquisition and disposal of a corpse had to be done in secret. So the school purchased bodies from freelance body snatchers and kept one full-time in their department.

Grandison Harris started at the Medical College of Georgia in 1852 as slave, but retired as an employee in 1908. Harris was purchased in 1852 in Charleston, South Carolina, and was owned by the entire faculty of the medical school, where he acted as a porter, janitor, teaching assistant, and resurrection man. After the Civil War, Harris became a full-time employee. Throughout his tenure, Harris stealthily robbed graves, purchased bodies of the poor and unclaimed for dissection, and quietly disposed of the remains in the basement.

When Georgia passed a law that made dissection legal in the state in 1887, it also provided a means by which medical colleges could get cadavers. But this legislation didn’t provide enough corpses for the school’s dissection tables, so Harris’ services were still needed.

Harris preferred to harvest corpses from the Cedar Grove Cemetery because this where Augusta’s poor and black populations buried their dead. This meant there was little security and the dead were interred in flimsy coffins.

Cedar Grove Cemetery in Augusta (photograph by Sir Mildred Pierce/Flickr)

Cedar Grove Cemetery in Augusta (photograph by Sir Mildred Pierce/Flickr)

Old Medical College Building in 2012 (photograph by Chip Bragg/Wikimedia)

Old Medical College Building in 2012 (photograph by Chip Bragg/Wikimedia)

An estimated 10,000 bones were recovered from the basement of the Old Medical College Building during excavations in 1989. These disarticulated bones were dispersed among old medical tools and trash from the lab. Archaeologists also found an old wooden vat, where lecturers stored bodies in whiskey, that still contained bones. Some of the remains showed evidence of dissection and had labels marking them as specimens.

Because many bones were cut up and scattered across the basement, it was extremely difficult for archaeologists and forensic anthropologists to determine ancestry, sex, or age of each individual. Analysis of the remains showed that 77% of the bones were male, and most of the remains belonged to African Americans. The excavation revealed that Harris likely threw the bones on the dirt floor and covered them with a layer of soil, then added quicklime to the surface to stifle the stench.

Medical College of Virginia

In 1994, a crew discovered an old well containing human remains and old medical trash while constructing a new medical sciences building on the campus of the Medical College of Virginia (MCV) at Virginia Commonwealth University.

The precursor to MCV was known as Hampden-Sydney College, opened in 1838. But it wasn’t until 1884 that the Virginia General Assembly passed the state’s first anatomy law, which also created the Virginia Anatomical Board. The board distributed to Virginia’s three medical colleges corpses belonging to criminals, the poor, and bodies that were not claimed. Like Georgia’s anatomy law, similar legislation in Virginia didn’t provide enough bodies for the lab tables, so resurrection men were still a necessary evil until the 20th century.

Historical records indicate that MCV had a janitor on staff named Chris Baker, who was the school resurrection man from the 1860s until his death in 1919. Baker stole cadavers from African American cemeteries and purchased them from Richmond’s poorhouses. When the students were finished with their cadavers, Baker threw what was left in an old well below East Marshall Street that became known as the “limb pit.”

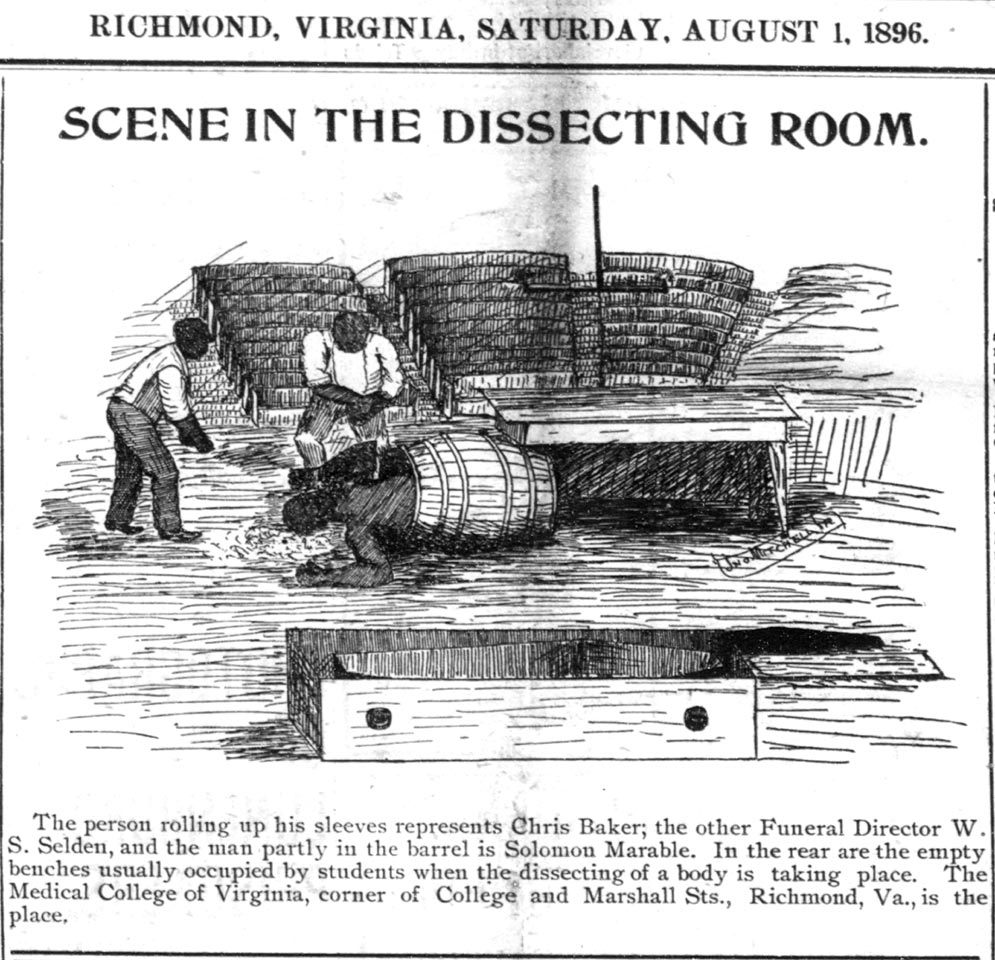

1896 newspaper illustration of Chris Baker with a funeral director in the Medical College of Virginia anatomical theater (via Library of Virginia)

1896 newspaper illustration of Chris Baker with a funeral director in the Medical College of Virginia anatomical theater (via Library of Virginia)

Baker was not as lucky as Harris because he was arrested or caught by police several times, and these encounters were reported by the local newspapers. Known as the “Ghoul of Richmond” he was something to be feared by the African American community and fuel for urban legends. African American children told stories that warned against going near the medical school at night because they might be taken by the Richmond ghoul or boogeyman. But Baker was also respected by Richmond’s medical community because he had a reputation as a loyal employee of the college and a self-taught anatomist. He died at his home on campus on June 8, 1919.

According to analysis conducted by forensic anthropologists from the Smithsonian, in the well there were at least 44 adults and nine children, and the remains belonged predominately to people of African American descent who were at least 35 years or older. Many of the bones showed evidence of surgical training and dissection, and some demonstrated perimortem trauma and disease. When archaeologists reached the bottom of the well, they found a second well that was capped and not excavated.

Harvard Medical School

During renovations at Harvard’s Holden Chapel in 1999, a worker operating a mini bulldozer stumbled across human remains when his machine broke through a wall into an old well. Holden Chapel, built between 1742 and 1744, became home to Harvard Medical School in 1801 and was used for anatomy lectures until 1850.

Holden Chapel in 2007 (photograph by GFDL/Wikimedia)

Holden Chapel in 2007 (photograph by GFDL/Wikimedia)

While Massachusetts had more liberal laws than other states when it came to dissection, it still did not provide enough learning material for medical students. As early as 1647, the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony allowed for the dissection of cadavers every four years, which is not enough for a medical school that regularly teaches anatomy courses. Massachusetts also permitted the bodies of executed criminals to be used for dissection, but anatomy classrooms were lucky if one body a year could be obtained from the gallows.

Since demand exceeded supply, students at Harvard Medical School needed the services of resurrection men to supply their labs. Sometimes these were employees of the school, and sometimes these were morbidly curious students.

Harvard University was home to the Spunker Club, also known as the Anatomical Club. Its members included anatomists and future doctors, but the club was not officially recognized by the university. Members of this clandestine organization robbed graves to get corpses for study, often in competition with other classmates. A few of the most well known Spunkers included Dr. John Warren, future professor of anatomy and surgery at Harvard; Samuel Adams Jr., son of the Founding Father; and William Eustis, a statesman and future governor of Massachusetts.

Spunkers understood that grave robbing was an art form that had to be perfected to avoid detection. John Warren, in a letter written in 1775, brags about the skill of his fellow Spunkers when a resurrection man left a grave open.

It was done with so little decency and caution … It need scarcely be said that it could not have been the work of any of our friends of the Sp–––r [Spunker] Club … where the necessities of society are in conflict with the law, and with public opinion, the crime consists … not in the deed, but in permitting its discovery. [As cited in Hodge (2012) p. 17)].

When Harvard Medical School opened its doors in 1782, Dr. John Warren was appointed Professor of Anatomy and Surgery. He insisted that the school provide a medical library, a dissection theater, and required students to demonstrate a thorough knowledge of human anatomy through cadavers.

Harvard Medical School in the 19th century (via Journal of American History)

Harvard Medical School in the 19th century (via Journal of American History)

To reduce the need for grave robbing, Massachusetts passed the Anatomy Act in 1831 that allowed the state’s medical schools to get bodies that belonged to the poor, insane, and those who died in prison. This law lessened the need for illicit bodies, but it didn’t eliminate it.

In 1842, Harvard Medical School employed a janitor named Ephraim Littlefield who supplemented his income by supplying students with cadavers, but it’s unclear if he was a resurrection man or just a middleman. He played a pivotal role in the infamous Parkman-Webster murder case. Littlefield’s eye-witness testimony led to the conviction of Dr. John Webster in the murder of Dr. George Parkman. He and his wife lived in the basement of the medical school, where he also disposed of the dissection waste in an old dry well, where it was were forgotten until 1999.

According to an osteological examination of the bones, the remains in the well belong to least 11 people, mostly adults. Archaeologists found bones from men and women, but most of the remains were so cut up that it was difficult to determine sex or ancestry.

Conclusion

In 1998 the bones from the Medical College of Georgia were reinterred in a mass grave at the Cedar Grove Cemetery with a plaque that says, “Known but to God.” Harris was also buried at Cedar Grove Cemetery in 1911, but the location of his grave was lost when the Savannah River flooded in 1929. Chris Baker was buried in an unmarked grave in Richmond’s Evergreen Cemetery after his death in 1919. The VCU community created the East Marshall Street Well Project to ensure that the remains are properly studied and memorialized. As for the Holden Chapel bones, it’s not clear if they have been reinterred, or if they have become part of a skeletal collection stored at Harvard.

University of Pennsylvania Medical School students with a cadaver (1890) (via University of Pennsylvania Libraries)

University of Pennsylvania Medical School students with a cadaver (1890) (via University of Pennsylvania Libraries)

For more fascinating stories of forensic anthropology visit Dolly Stolze’s Strange Remains.

References:

Grauer, A. (1995). Bodies of Evidence: Reconstructing History through Skeletal Analysis. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss.

Hodge, CJ. (2012). Non-bodies of knowledge: Anatomized remains from the Holden Chapel collection. Journal of Social Archaeology. Retrieved from: http://www.academia.edu/2517397/Non-bodies_of_knowledge_Anatomized_remains_from_the_Holden_Chapel_collection_Harvard_University

Holmberg, M. (2010 November 17). Meet Chris Baker – Richmond’s grave robber. CBS6. Retrieved from: http://wtvr.com/2010/11/17/mark-holmberg-meet-chris-baker-richmonds-grave-robber/

Kapsidelis, K. (2011 November 11). Confronting the story of bones discarded in an old MCV well. Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved from: http://www.richmond.com/news/article_4a784033-ca30-5a30-be4d-80c7fd9a3783.html

Lonergan, JM. (1999 July 9). Human Bones Found During Holden Chapel Renovations. The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved from: http://www.thecrimson.com/article/1999/7/9/human-bones-found-during-holden-chapel/

Lovejoy, B. (2014 May 6). Meet Grandison Harris, the Grave Robber Enslaved (and then Employed) By the Georgia Medical College. Smithsonian. Retrieved from http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/meet-grandison-harris-grave-robber-enslaved-and-then-employed-georgia-college-medicine-180951344/

Owsley, D. and Bruwelheide, K. (2012 June 18). Artifacts and Comingled Skeletal Remains from a Well on the Medical College of Virginia Campus: Introduction. VCU Scholars Compass. Retrieved from: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=arch001

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook