This Cookbook Explores Why ‘Rice Is Culture’

Chef JJ Johnson takes readers on a global culinary tour.

Humans have cultivated rice for nearly 10,000 years—thousands of years before what many archeologists consider the rise of civilizations. Rice has formed the backbone of empires, the basis of political alliances, and to this day remains a primary food staple for some 3.5 billion people.

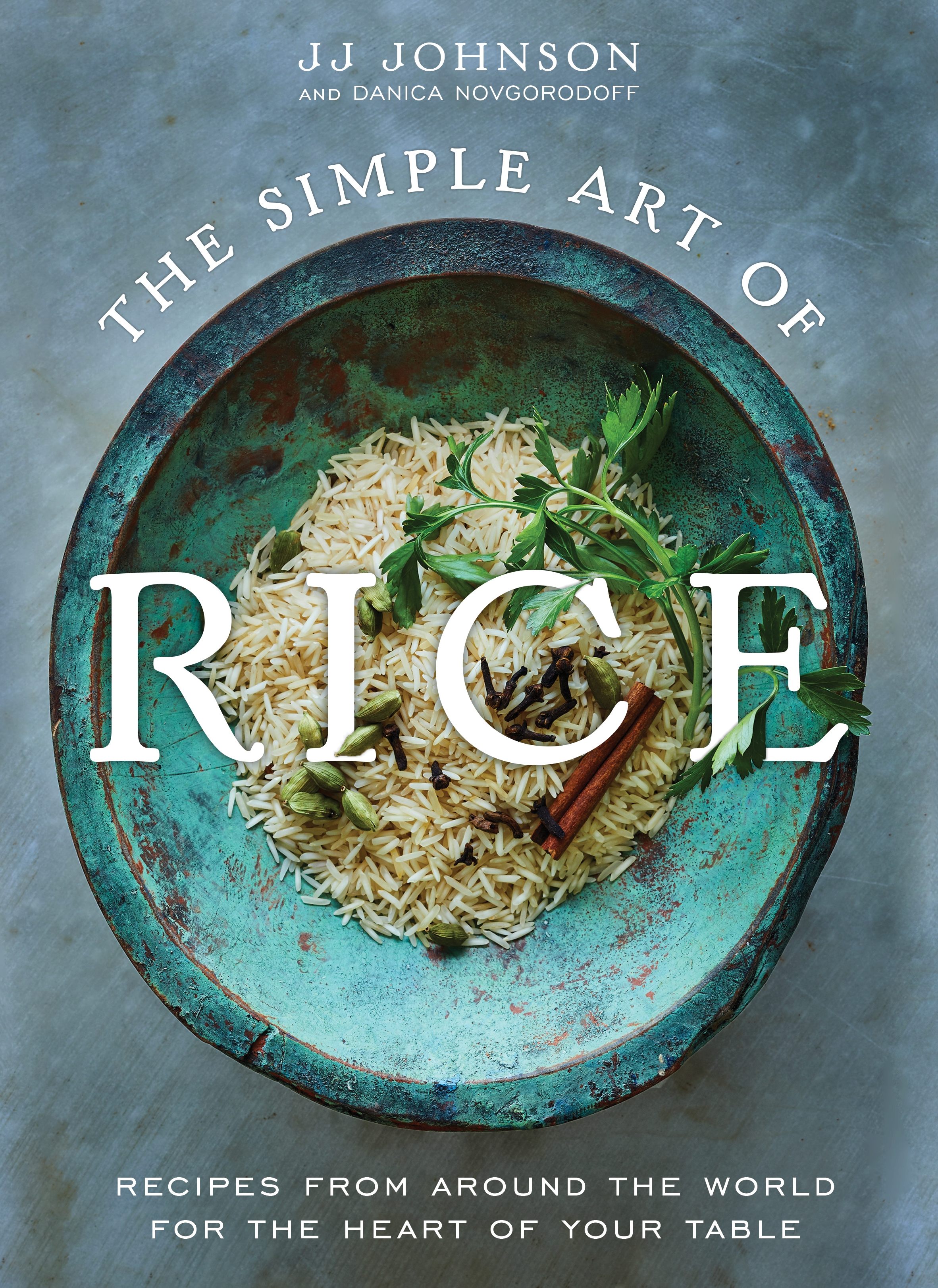

In 2019, when Johnson opened FieldTrip, a fast-casual restaurant in Harlem, a sign hung on the wall declaring “Rice Is Culture.” In his latest cookbook, The Simple Art of Rice: Recipes from Around the World for the Heart of Your Table, the James Beard award–winning chef expands that thesis into a manifesto, one that examines the history of how rice dishes have changed across both voluntary and forced migrations around the world. It’s a deeply researched work and a highly personal one, a reflection of his own Afro–Puerto Rican roots and learnings gathered through his extensive travels around the globe.

More than anything, Johnson seems interested in drawing connections, from America’s complicated history with growing heirloom grains to its present, and from one culture’s rice tradition to the next. He notes how thieboudienne, Senegal’s magnificent rice dish crowned with whole fried fish, is the ancestor of dishes served among Gullah Geechee communities throughout Georgia and the Carolinas, or how Charleston’s shrimp perloo has roots that stretch back to Middle Eastern pilau or pilafs. He explores a whole series of fried rice variations, from a Nigerian recipe with lamb to a Peruvian number with chicken—a nod to the lasting impact the continent-spanning Chinese diaspora has had on different cuisines.

In the process, he whisks readers from his grandma’s table, which often sported a heaping dish of dirty rice, to the hawker stalls of Laos. Gastro Obscura spoke with Johnson about Liberian jollof, why we should all be eating more Carolina Gold rice, and the heirloom grains in a duck farm near you.

Quite a few of the dishes in the book are both so beloved and so varied by region or country. How did you choose, say, to showcase Liberian jollof rice instead of Nigerian or Senegalese jollof?

I picked Liberian jollof because I wanted to show people that Liberian jollof is very similar to jambalaya. You can then trace it [and see how] jollof has morphed into a different name or a different being. So that’s why I picked that. There are also a lot of Liberians in Harlem that cook jollof really well, and I hope to give them a voice. I hope I didn’t let them down.

Are there any rice dishes that are personally resonant for you or have a story that really stayed with you?

There’s my grandmother’s asopao, a soupy rice dish from Puerto Rico that I love. And the sweet, spiced brown rice porridge is something I make for my kids. When we’re not doing oatmeal, we do rice.

The beef-and-rice-stuffed collard greens are traditionally done with grape leaves. I did it with collard greens my way, and that was very significant to Carrie Rashkin, who’s my chief of staff, because when she saw that, she said, “Oh I don’t need the grape seed leaves anymore. We don’t have to pull out the stems! I’m going to tell my mom.”

I think that the greatest part of the book was talking to David Chang or Dr. Jessica Harris or Glenn Roberts and seeing how everybody connects to rice in this very significant way to them, which might not be the same way it connects to me.

From your work with FieldTrip to the book, you’ve been working with rice for a while. What drew you to it conceptually?

Everywhere I traveled in the world, rice was always an ingredient that people celebrated around. It has this rich history [in the U.S.] as a cash crop. It’s significant to Black America, significant to America as a whole, significant to the world.

I wanted to bring back the rice culture of America. FieldTrip, yes, it’s a small, fast-casual chain that’s growing, but I think it has had a bigger impact [because] of the varieties of rice that we’re serving. The Simple Art of Rice will hopefully connect to that and will then allow this big conversation around the rice culture of America and the world to keep growing.

Are there grains that stand out to you, ones that you wish more people were using, or ones that you think are particularly exciting?

I think everybody in America should be buying Carolina Gold rice. I think Carolina Gold rice is closer to you now than you ever have imagined. I think there’s also an heirloom or really good grain in your backyard. If you live in New Jersey, there’s Blue Moon Acres [farm]. If you’re in the Hudson Valley, there’s Ever-Growing Family Farm.

If you’re in Vermont and you know a duck farmer at the farmers’ market, ask them if they grow rice. Just because of the irrigation of water flow, they probably have grown rice or that field has grown rice. Or even your crawfish farmers in Mississippi grow rice.

How have your travels influenced both the work in this book and your growth as a chef?

I used to think, working in New York City, you didn’t have to travel to evolve as a chef or as a cook. I was so wrong. The moment I traveled to Ghana, I found myself through food. I started cooking differently.

Traveling will impact the way you view food and the way you view people. I was in Cartagena and it reconnected me with this Afro-Latino side of me that I want to express more of in cooking. Travels have helped me to be able to open a restaurant like FieldTrip, be able to write this book, and also just be able to respect culture. I might not agree with everything you do in your culture, but I can respect it because I’m eating your food, and I can feel you in your food. And that means something great.

Singapore, Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, India, Ghana have all been able to shape who I’ve been or who I’m becoming. I think rice is able to shape people when they’re looking for culture. Maybe you have a simple biryani recipe and hopefully when you cook it, you’re like, “I need to go to an Indian restaurant now” or maybe it’s “I don’t know what to do for the holidays, but there’s thieboudienne and I heard them talking about West Africa on television. Should we try to make this for Thanksgiving?”

Hopefully it will allow people to feel some type of comfortability, some type of awareness, and open us up during a time when we need to be reconnected more than ever.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook