A Visit to Chernobyl as It Transforms Into a Solar Farm

Energy production is about to resume at the site of the worst nuclear accident in history.

In April 1986 the nuclear accident at Chernobyl devastated a large swathe of land in the north of Ukraine. The workers’ city of Pripyat was evacuated, to become one of the world’s most notorious ghost towns—while dozens of villages in the vicinity of the nuclear power plant were similarly deserted as radiation polluted earth, air, and water alike. At the very heart of the Exclusion Zone however, the plant itself would remain a hub of activity.

Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant (NPP) was still producing energy for 14 years after the accident at Reactor 4. In the wake of the disaster, amid the rubble and radiation, it was safer to allow the remaining fuel rods to burn out in their own time, rather than trying to remove them. Reactor 2 wasn’t shut down until after a fire in 1991; Reactor 1 followed in 1996. Reactor 3 was in use until December 2000, and since then Chernobyl has produced no energy at all—until now.

The Ukrainian-German project Solar Chernobyl is preparing to launch a solar farm right next to the Chernobyl reactors. Due to go online early in 2018, the one-megawatt installation features 3,800 photovoltaic panels and will be capable of powering as many as 2,000 homes. A further 99 megawatts are planned for a future development, and the project, which has so far cost a million euros ($1.25 million) to build, is expected to pay itself off within seven years.

Ukraine currently has 12 active nuclear power plants, but it is no stranger to solar energy. It has been reported that Solar Chernobyl is the country’s first solar farm, but this is in fact the fourth such installation built on Ukrainian territory.

The Okhotnykovo and Perovo Solar Parks, in Crimea, were both commissioned in 2011—generating 82 and 100 megawatts respectively. A third was brought online in 2012, the 42-megawatt Starokozache Solar Park near Odessa in south Ukraine. Following Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, however, Ukraine lost its two largest solar farms. With Russian natural gas supplies now similarly cut off, the new installation at Chernobyl, though far smaller than the nuclear site’s original output of four 1,000-megawatt reactors, is nevertheless a welcome step in the direction of energy independence.

For Chernobyl NPP itself, the project spells another welcome development: financial investment.

Dealing with the irradiated remains of Reactor 4 poses the greatest ongoing cost for the plant. In October 2017 the New Safe Confinement, a colossal radiation containment dome, was installed over it, at a cost of €1.5 billion ($1.8 billion). Built by a French consortium, the structure is hermetically sealed and fitted with remote controlled cranes with which to dismantle the reactor inside. A new radioactive waste storage facility has also been created nearby, where up to 75,000 cubic meters of hazardous materials can be safely stowed underground. While Reactor 4 is gaining a lot of international attention and investment, however, Ukraine is largely alone in decommissioning Chernobyl Reactors 1, 2 and 3.

Inside Reactor 2, scientists and other staff dressed in white protective suits walk swiftly through archaic, 1970s Modernist interiors. The so-called Golden Corridor, leading to the reactor’s control room and upwards from there to the core, is decorated in ribbed metal panels and Art Deco tiling. It looks like a power plant designed by Wes Anderson, and staffed by the cast of A Clockwork Orange… and it is bitterly cold in winter.

As temperatures outside drop to around -12 C (10 F), the unheated interior of Reactor 2 is close to freezing point. Protective garments are provided and visitors shiver as they strip to their underwear, walking half-naked to the next room to don starchy cotton suits, gloves, slippers and masks. Later, in the Golden Corridor, a worker passes the group. Over the same white pajamas he wears a thick blue jacket stenciled with the power plant’s initials in Cyrillic: “ЧАЕС.” Envious gazes follow him down the corridor.

“It’s too cold here,” says Anton Povar, a station guide who deals with official delegations and the occasional tour group. A regular stream of engineers, inspectors, and journalists visit the reactors, and the experience is also sometimes offered to tourists for a surplus fee. None of that money seems to go back into making it comfortable though, either for workers or for visitors. “We don’t have enough radiators,” says Povar. “We don’t even have enough winter coats for everyone.”

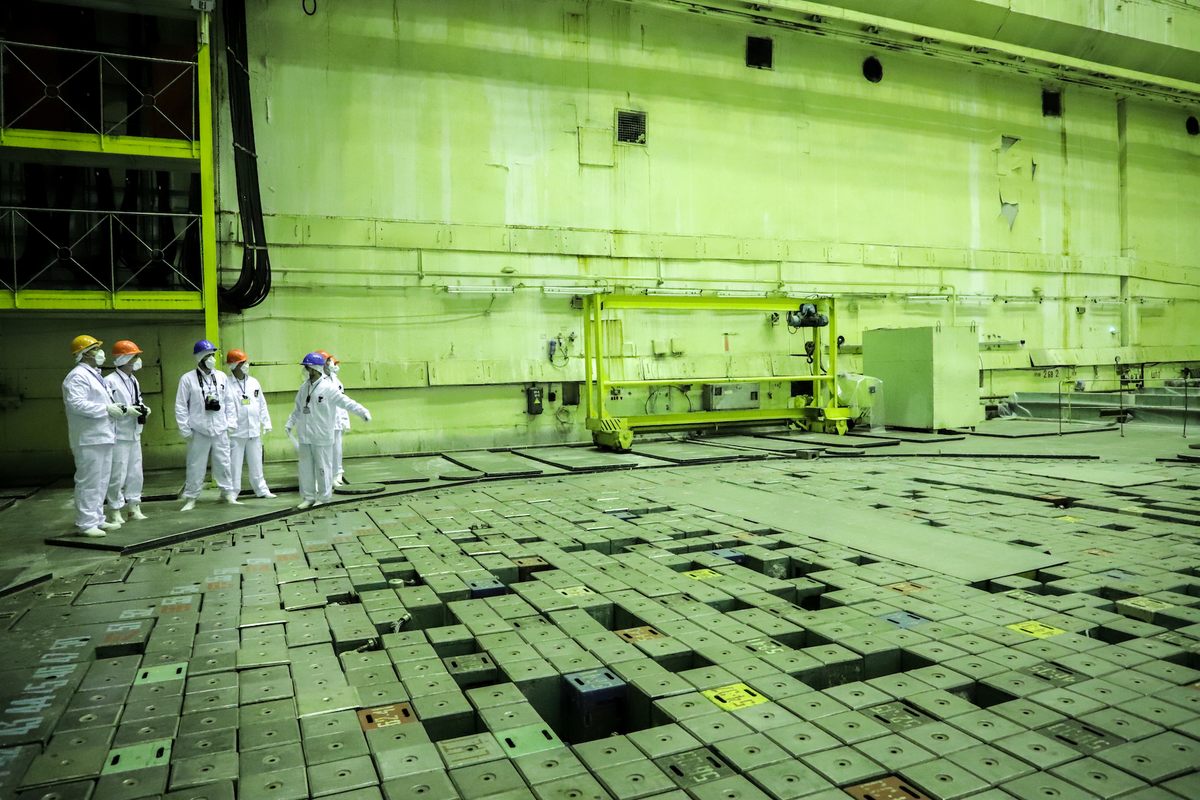

After conducting a tour of the Reactor 2 control room, Anton leads the way up a pitch black stairwell to the reactor chamber. In the absence of light bulbs, half a dozen mobile phone screens illuminate the steps.

The decision to lease land at Chernobyl NPP to solar energy companies brings valuable new revenue to an alarmingly underfunded decommissioning project.

The original plan for the Chernobyl site was to build a block of 12 nuclear reactors, located 80 miles north of the Ukrainian capital. At the time of the accident in 1986, Reactors 1 through 4 were already online while 5 and 6 stood semi-completed. The ground had already been prepared for Reactors 7 and 8; and today the power plant still controls the land designated for the full 12-reactor block. Combined with Chernobyl’s still-intact electrical transformer substations, capable of handling and redirecting huge power outputs, the creation of a natural energy plant at the site makes a lot of sense.

Even as that lease money trickles in, though, other sources of income at the plant are dwindling. “In 2016 the power plant had 6,000 visitors,” says Anton. “Last year that number went down to 4,500.”

While Chernobyl’s ghost towns are attracting more visitors each year, the plant seems unable to capitalize on these numbers. These days, Anton Povar finds much of his time is spent leading foreign journalists down the Golden Corridor.

“For me, the journalists are the worst,” he sighs. “They all want to find something sensational to write about, but we are just a decommissioned power plant… there’s nothing sensational for them here.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook