The City the Chernobyl Disaster Left Behind, Then and Now

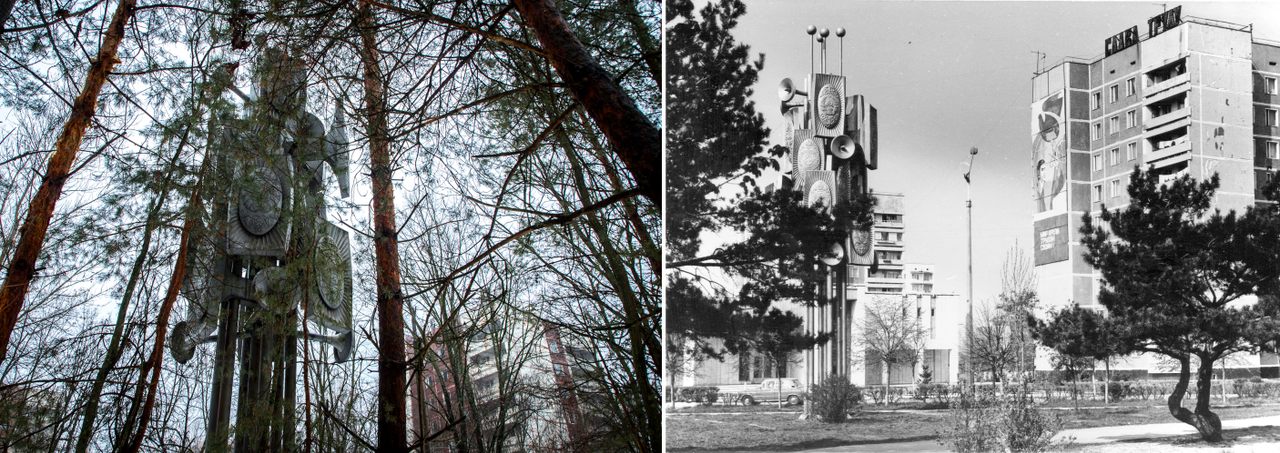

Archival images of Pripyat before the accident offer a stunning contrast to what visitors will find today.

Built to house the workers of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, by 1986 Pripyat was a thriving atomgrad. Schools and kindergartens, a cinema, palace of culture, swimming pools, river port, and a respectable selection of shops and cafés—all these amenities served the city’s young populace, by then numbering nearly 50,000 residents. New administrative districts were under construction in anticipation of further growth. Pripyat offered a standard of life above and beyond that of many contemporary Soviet cities, so much so that, “to men and women born in the sour hinterlands of the USSR’s factory cities… the new atomgrad was a true workers’ paradise,” as Adam Higginbotham explains in his recent history of the disaster, Midnight in Chernobyl.

The city of Pripyat stood in the front line of that disaster—just a couple of miles from the ill-fated plant—and now, in the 33 years since the last human resident left, nature has reclaimed it.

In 2017, the most recent year for which figures are available, an estimated 60,000 paying visitors entered the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. A search for #Chernobyl on Instagram brings up hundreds of thousands of hits, many illustrating a new visual language of the post-disaster landscape: gas masks, headless dolls, souvenir kiosks. The historical authenticity of such scenes is often questionable, but beneath the dense green vegetation, amid thickets of new-grown forest, survive real fragments of this would-be utopia gone to ruin.

Higginbotham’s Midnight in Chernobyl includes a moving selection of archival images from Pripyat. They’re moving, often, because they’re just so blissfully mundane. Children squat in a playground, drawing chalk lines on the tarmac; retirees gossip on benches; majorettes march out of sync; seemingly everywhere, there are families pushing prams.

Many of those archival photographs are impossible to reproduce now that the forest has moved back in. Vantage points that once offered views of broad, open boulevards are cocooned now by tightly woven trees. In summer, the leaves draw in close around the shells of former buildings, cutting each off from its neighbors. Roads are invisible. Paving stones lie buried under decades of dirt and moss. The football field, now thick with vegetation, is recognizable only by the spectator stalls that face onto a solid rectangle of forest.

This disconnect between past and present, between nostalgic family photos and the half-buried city—a post-modern Pompeii explored by tens of thousands of international tourists—can only expand. Nature is relentless. Trees have snuck up on the Ferris wheel in Luna Park. Pripyat’s School No. 1 has lost an outer wall, leaving third-floor classrooms open to the sky. The city’s main thoroughfare, Lenina Avenue, has shrunk from a two-lane boulevard lined in sidewalks and neat grass to a single dusty track flanked by undergrowth so dense that, in summer, it’s hard to see the houses for the trees.

Official Chernobyl tours, heavily regulated by the Ukrainian government, offer less each year to the growing number of visitors. The city of Pripyat is falling apart, and the death of a tourist could do serious damage to what is now a multimillion-dollar industry for Ukraine. Rules about not entering the buildings, typically somewhat lax in the past, are increasingly being enforced. The modernist diving board at Pripyat pool was until recently one of the most popular photo targets in the city, but the installation of motion detectors has now ensured its removal from itineraries.

It is already difficult to reconcile these forest ruins with the lives that once inhabited them. Some enterprising companies are now offering premium helicopter tours over Pripyat, and one day, when the roads become impassable and the entire area is deemed unsafe for tourists, these may be the only views that are left: concrete skeletons breaking above the surface of the forest, and the sarcophagus over Chernobyl’s Reactor 4 shining silver on the horizon. In the meantime, the atomgrad, consumed by nature, sinks to the forest floor, taking its memories, nostalgia, and political aspirations with it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook