The Debonair Restaurateur Who Inspired the First Chinese-American Cookbook

Chin Foin forever changed America’s relationship with Chinese food.

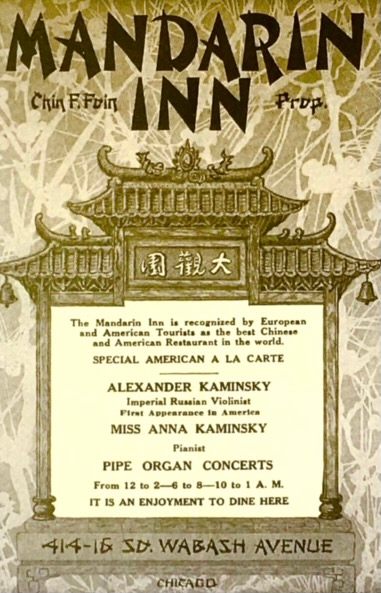

On March 29, 1924, Chin Foin, the wealthiest restaurateur in Chicago’s Chinatown, was found dying at the bottom of an elevator shaft in his own business, the Mandarin Inn. Some said it was a tragic accident, while others suspected foul play. Chin’s wife wondered if her own brother had given her husband a fatal push in a fit of jealous rage. Others suggested it was the work of one of the tongs, the local Chinese crime syndicates.

Prior to his untimely death, Chin Foin had done his best to steer clear of the tongs, but not many business-owners at the time had much of a choice when it came to avoiding criminal organizations. Nancy Wang, Chin’s granddaughter, remembers hearing tales about how Al Capone patronized one particular Chinese restaurant on the regular. “He would hand a $100 bill to every waiter,” she says. “That was how he ensured he was safe, because he was always a target. But he loved his Chinese food.”

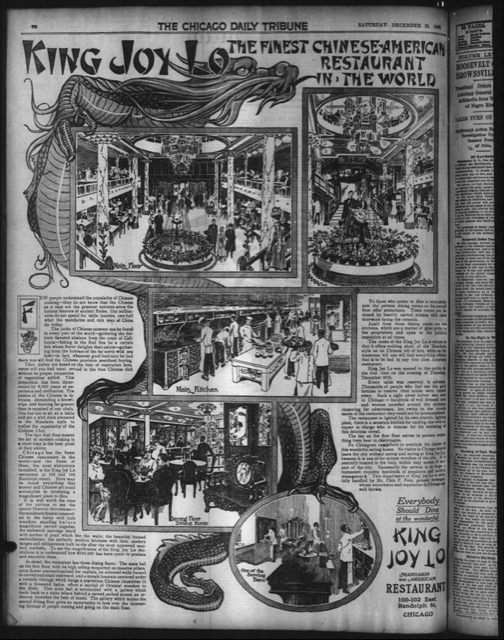

Capone wasn’t alone. During the early 20th century, Chinese-American dishes became staples across the United States, in no small part thanks to Chin Foin. In an era when Chinese immigrants faced blatant racism and limited social mobility, Chin Foin used food to climb to the top of Chicago’s socioeconomic ladder, right into the heart of elite white society. His restaurant empire, consisting of King Yen Lo (opened in 1902), King Joy Lo (1906), and, above all, the Mandarin Inn (1911), forever changed perceptions of Chinese-American cuisine and inspired the first English-language Chinese-American cookbook.

In 1911, Chicago-based journalist Jessie Louise Nolton published Chinese Cookery in the Home Kitchen, which is believed to be the first English-language cookbook dedicated to Chinese-American cuisine. “They took some of the recipes from [Chin Foin’s] cooks,” Wang claims. Yet Nolton never explicitly references Chin Foin by name, stating simply that she learned from “Chinese cooks of great reputation.” But the proximity of her office to the Mandarin Inn and his other restaurants, as well as their unrivaled prominence in Chicago, means she was almost certainly influenced by them. Her 135-page book was clearly written with the intention of introducing white, middle-class American readers to previously unfamiliar dishes. “The favorite dishes of the Orient are rapidly becoming the favorite dishes of the Occident,” Nolton wrote.

But before Nolton’s book, Americans went out to eat Chinese food. Around the turn of the 20th century, cities saw a huge proliferation of humble “chop suey joints,” says Andrea Stamm, chair of Collections and Research at the Chinese American Museum of Chicago. But Chin Foin changed everything. “In Chicago, the Mandarin Inn and King Joy Lo restaurants set a new standard for Chinese restaurants,” Stamm says, and inspired a wave of “upscale Chinese eateries that catered to an urban nightlife crowd.”

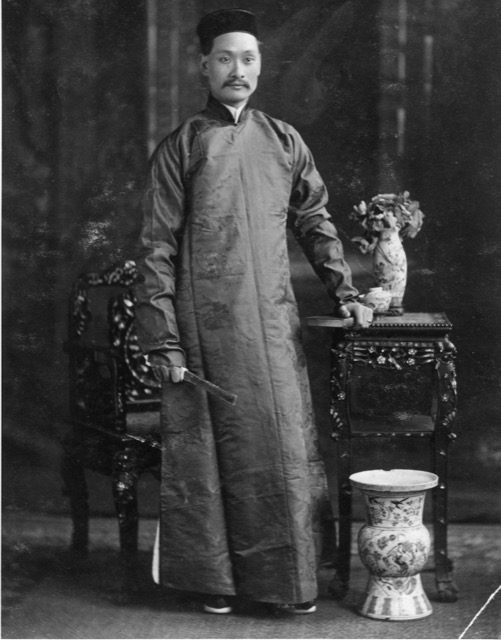

An entrepreneur with a keen business acumen and a flair for the dramatic, Chin Foin spent his evenings mingling with guests in a tuxedo or at his private box in the opera, where he could often be spotted wearing a flowing dark cape. Stories about him abounded—he was a skilled horseback rider; he spoke German; he had gone to Yale (a fact his granddaughter says she has not been able to verify). A newspaper announcement of his 1904 wedding described him as “the wealthiest Oriental of his Age in America.”

“None of us grandchildren met him, but we always heard that he was everyone’s hero,” Wang says. “He was so smart and so handsome. He himself had his portrait painted and there he is, looking very dapper in a high-collared shirt with a cigar in his hand.”

The man the same newspaper described as a “Chinese plutocrat” came from modest beginnings. Born 1876 in Taishan, Guangdong province, Chin Foin emigrated to San Francisco with his family as a teenager. Like many Chinese immigrants, he found the reception on the West Coast to be less than welcoming. The United States had passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 and xenophobia was running high among local white union workers. “The anti-Chinese sentiment came from several special interest groups, primarily white laborers and farmers in California who viewed the Chinese immigrants as competition,” says Dr. Huping Ling, author of Chinese Chicago: Race, Transnational Migration, and Community Since 1870. “Of course, there were also racist sentiments involved. Chinese immigrants were seen as unassimilable.”

A visit to the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago gave the family an idea of where they could start a new life. At the time, Chicago’s Chinatown was on the rise, in part due to Chinese immigrants migrating to the Midwest to escape the hostility they were encountering in California. After arriving in Chicago in 1895, Chin Foin picked up a job as an assistant manager at Wing Chong Hai, a grocery store on 281 Clark Street owned by some distant relatives. Nine years later, the enterprising young man had saved up enough money to break into the restaurant business. Chin Foin’s first foray into the culinary world, King Yen Lo, heavily emphasized chop suey, chow mein, egg foo young, and other Cantonese-inflected Chinese-American dishes of the time.

Although the business was located above a saloon, Chin Foin went to great lengths to decorate it as lavishly as possible to appeal to the theater-going crowd. “Most Chinese couldn’t go out to eat, so he knew that the people that were eating out were the more wealthy white people,” Wang says.

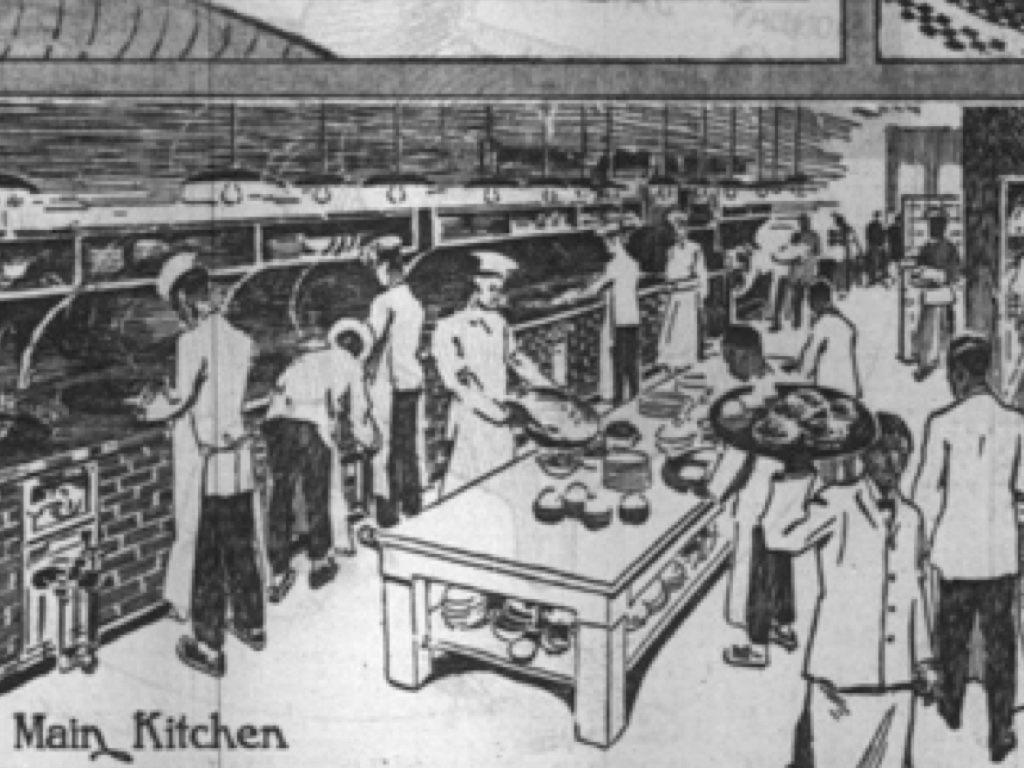

With each subsequent restaurant, Chin Foin went to greater lengths to increase the opulence and appeal both to visiting Chinese dignitaries and elite society in Chicago. Even King Yen Lo featured an orchestra, as well as an open kitchen policy to emphasize its cleanliness—a direct attempt to counter the negative stereotypes swirling around Chinese-owned restaurants at the time.

By 1911, when he opened the Mandarin Inn in the downtown Loop near the opera house, Chin Foin was a well-established figure in Chicago. To celebrate the opening, he took out a full-page ad in The Chicago Tribune, declaring his new endeavor to be the home of “the only correct Mandarin cooking in Chicago.” The restaurant was his most lavish yet, with an interior aesthetic that married Orientalist tropes with the Western-style white linens and other fine dining trappings of the day. “[The Mandarin Inn] set up a place for Chinese fine dining and it provided a contrast from the stereotypical image at the time of Chinese immigrants as poor and running small mom-and-pop restaurants,” Ling says. “In that sense, it’s very significant.”

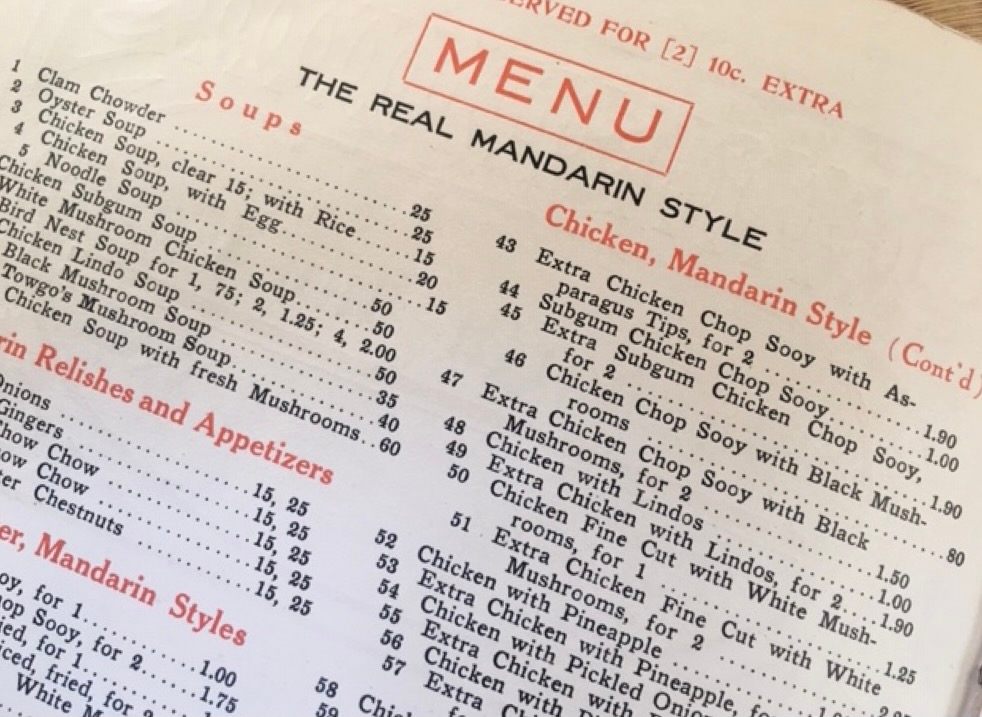

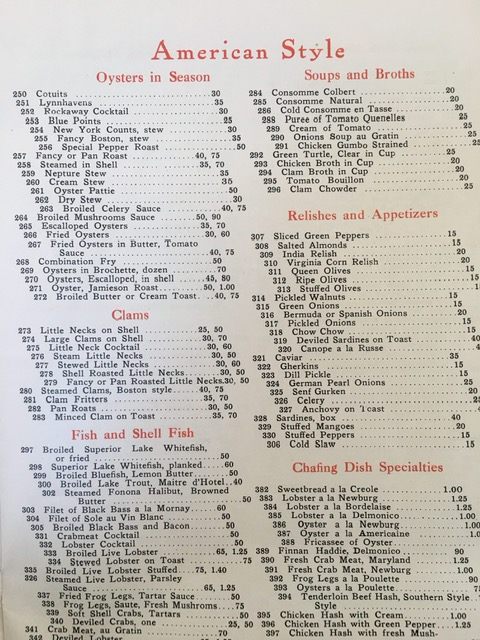

The menu at the Mandarin Inn was culturally split down the middle. According to Wang, it featured four pages of chop sueys, including variations with squab and oyster, followed by several pages of Western American dishes, and an extensive selection of fine liquors and cordials. “He made it very fancy, knowing that was what was needed to attract that audience,” Wang says. “At the time, people felt that they were worldly if they ate Chinese food. Every night, he was in a tuxedo and he mingled with his clientele. He became kind of a figure in that upper class.”

Chin Foin went to great lengths to counter the prevailing anti-Chinese and anti-Asian attitudes for a good reason. A series of legislative proposals in Chicago from 1906 and 1911 attempted to levy all sorts of additional taxes, fees, and limitations on Chinese restaurants. In The War on Chinese Restaurants, University of California at Davis law scholar Gabriel “Jack” Chin writes that when the Chicago City Council considered a 1906 proposal that would limit restaurant-ownership to U.S. citizens, The Chicago Tribute stated that “the Chinese would be permanently banned as they cannot become citizens” and that one member of the assembly publicly stated that Chicago “could get along without any chop suey places.”

In 1910, the year before the Mandarin Inn opened, an article in The Chicago Tribune declared, “The laws of morality and health, police regulations, and practically all the other protective measures are being violated openly by many chop suey establishments.” Although it was never successfully passed, at the American Federation of Labor convention in 1913, organizers attempted to make it illegal for white women to frequent Chinese- or Japanese-owned restaurants at all.

As prominent as he was, in 1912, Chin Foin’s attempt to move his family into the affluent, predominantly white neighborhood of Calumet on the South Side was met with uproar. The Chicago Tribune described the family’s arrival as an “invasion” and quoted neighbors lamenting how “cosmopolitan” the area had become. “The white people were up in arms,” Wang says. “Finally, some of them said, ‘Well, if he can keep it up, he’s welcome. He won’t be like other scallywags that came to our neighborhood.’”

By some accounts, Chin Foin may have been reaching the end of his patience in the months before his death. Prior to that fateful fall down an elevator shaft in 1924, he had been planning to travel to China with his family for an unknown length of time. Instead, he tragically perished, leaving behind a flourishing business and a grieving family. At the time, his death was ruled an accident, which his granddaughter acknowledges may well be true. “It could also be that his shoes were slippery, because he always wore leather shoes with his tuxedo,” Wang says.

Nevertheless, Wang thinks a number of elements about the story seem fishy. In her 2019 play, Shadows & Secrets, she delves into the possibility that the tragedy that befell her grandfather may not have been an accident at all. She questions the fact that the night before he was set to return to China, he met such a shocking end. Chin Foin’s death remains a mystery, but she, like her grandmother, suspects that a relative or a rival may have had a hand in it.

“There was this big rivalry between the Moy family and the Chin family,” Wang says. “My great-grandfather, who was the head of the Chin association, hired a very famous lawyer to help prosecute the Moys for killing someone who was part of the Chin family association. The guy got on the stand, and he said, ‘Well, I only got to kill one but I was asked to kill four more’ and he pointed to my grandfather, my great-grandfather, and my two uncles.”

While Chin Foin’s success in life seemed to defy the odds, what happened after his death was sadly predictable. The family fortune largely fell apart. His widow took up a job in a tailor shop to make ends meet. King Joy Lo and the Mandarin Inn both passed to new owners; the former was reopened as a different restaurant and the latter shuttered in 1928.

Chin Foin may have passed away before his time, but his willingness to challenge the social norms of the time had a powerful impact. Other cookbooks followed Chinese Cookery in the Home Kitchen, just as other ambitious Chinese restaurants followed in the wake of the Mandarin Inn. He may have mostly set out to make a better life for himself and his family, but in the process, he struck a blow against the prevailing racism of his time and paved the way for the next generation of Chinese-American restaurateurs.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook