Sold: Charles Dickens’s Liquor Log

Dickens spent the days before his death counting casks of whiskey.

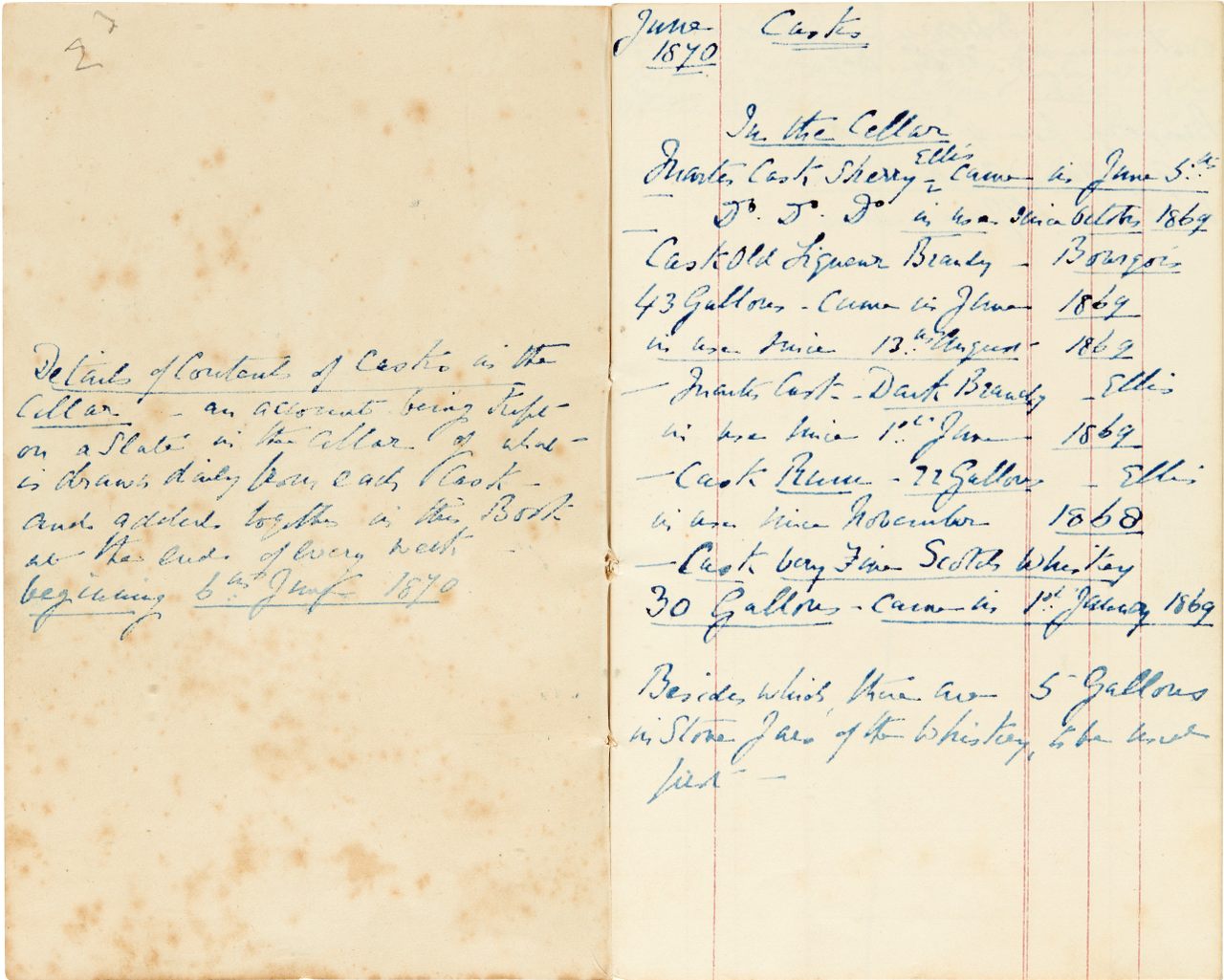

On June 6, 1870, Charles Dickens strolled into the cellar of his country house, Gad’s Hill Place in Kent, and surveyed his liquor stores. The day before, wine merchants at Joseph Ellis & Sons had dropped off a cask of good sherry. If Dickens wanted whiskey, he could dig into stone jars of it, including some of the 30 “very fine” gallons that had been delivered the previous January.

But Dickens was expecting company—his daughters were coming to visit. So, as he often did when guests came to visit, the writer took stock of his intoxicants and recorded the inventory in a clear, firm hand in his household notebook. Three days later, after a sudden brain hemorrhage, Dickens was dead.

The notebook remained. Passed for years through the hands of various manuscript collectors, the yellowed notebook, bluish with Dickens’ spidery script, was auctioned off on September 24 by Sotheby’s, London. Selling for £11,875 or $14,641, it was one of many Dickens-related items auctioned off from the collection of Lawrence Drizen for more than two-million dollars.

“There’s a hugely passionate collector community for Dickens,” says Gabriel Heaton, a Specialist from Sotheby’s Books and Manuscripts Department. Those that participated in the auction had their pick of Dickens classics, including first editions of Great Expectations, which sold for $217,350, and A Christmas Carol, which sold for $116,438. But the humble household inventory had something these great works didn’t: It was one of the last things Dickens wrote.

Like many estate-owners of his time, Dickens maintained a hearty liquor cellar, which he tapped into to entertain the guests who frequented his country estate. He kept casks of sherry, pale and dark brandy, whiskey, and rum. His personal alcohol use “was pretty normal for the time,” says Heaton (the Victorians liked to drink). He didn’t keep gin, which was considered a drink of the poor.

Unlike other men of his class, who might have commissioned staff to track the daily ins and outs of cellar stock, at the end of his life, Dickens chose to attend to this household matter himself. “He was a man who was always full of energy,” Heaton says. Yet by June 1870, while Dickens was still hard at work on his last novel, the never-completed The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Dickens had begun to lose mobility. Unable to walk the grounds, his attention turned inward.

For Heaton, the creation of this painstaking household inventory is evidence that, faced with this declining mobility, Dickens focused on routine, and on daily matters of food, drink, and entertaining. “It’s a poignant record of the final days of one of the greatest writers in the language,” Heaton says.

What will your “household inventory” look like in a couple of hundred years? Let us know, and share any other thoughts and feelings you might have about the story in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums!

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook