Can an Old Coin Solve the Mystery of a Lost Roman Emperor?

Examining whether a ruler slipped through the cracks of a tumultuous century.

Paul Pearson has always been fascinated with ancient human history, even though his professional area of interest is more like earth science and paleoclimate. Pearson, of Cardiff University in the United Kingdom, has indulged his interest in the Roman Empire for a long time, and in March 2022 published The Roman Empire in Crisis, 248–260: When the Gods Abandoned Rome, a book focused on a particularly challenging stretch of Roman history. In the third century, the empire was plagued by a series of civil wars, economic turmoil, an empire-wide pandemic, and a succession of leaders and usurpers vying to rule the sprawling Roman world. Pearson didn’t expect to stumble on an ancient mystery as well. “It was while writing that book that I came across an interesting story of an obscure emperor who was believed to have been fake because he was based entirely on fake coins,” he says.

In 1713, eight gold coins of five different designs were dug up in Transylvania, in modern-day Romania, and acquired by a man named Carl Gustav Heraeus. One of them featured a face and the name “Sponsian.” Roman coins bore the faces of the ruler who issued them, even if his reign had been brief. The eight coins were discovered to have come from a larger hoard of gold coins that had been spread around at the time. Four Sponsian coins from that hoard are known to exist today. However, Sponsian’s name doesn’t appear in any ancient texts or sources. Over the years, the coins were written off as fakes—and the emperor was, too.

Pearson decided to look into the story behind this obscure possible emperor as an entertaining digression from the grim book he was writing. “I thought it was an interesting story to research,” he says, “partly because it seemed like there was a slightly puzzling issue explaining how that came to be.”

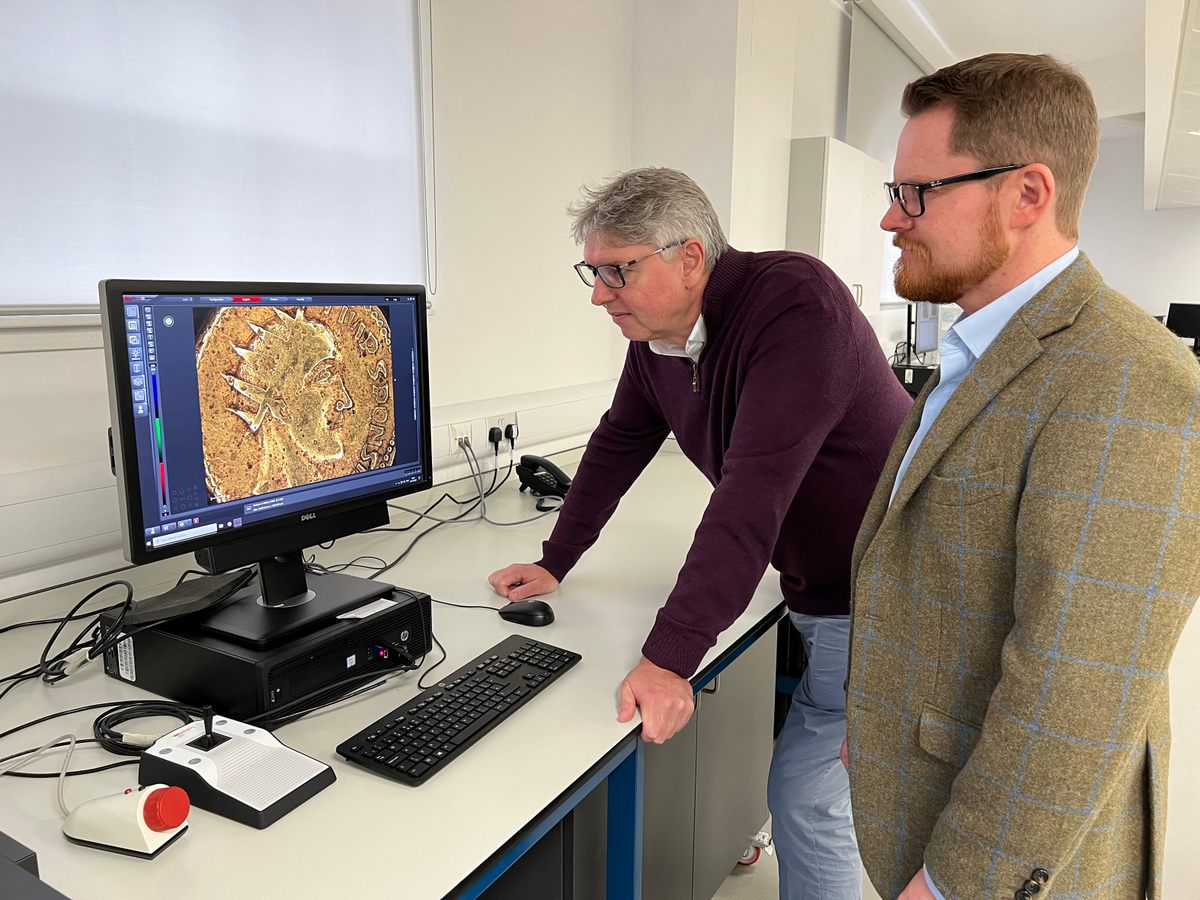

While doing his early research, Pearson realized that there were no clear photographs of the slightly infamous coins anywhere. “There were some grainy black-and-white published photographs, but nobody had ever had a close look at these coins.” He learned that the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow had one of the Sponsian coins and three others of similar design, depicting Gordian III and Philip (I or II), both of whom were real emperors with brief reigns during the tumultuous third century. So Pearson emailed Jesper Ericsson, the museum’s curator of numismatics, to request a photograph of the Sponsian coin. “We were both quite puzzled by the appearance of it,” he says, “which had indications of being deeply worn and having incrustations on the surface.” Why would a forgery appear to have spent a long time in the ground? Unsure of what it all meant, Pearson and Ericsson assembled a team for a study to get to the bottom of the mystery.

The study, recently published in the journal PLoS, examined the four coins in the Glasgow collection, in addition to two other Roman gold coins of Gordian III and Philip I that are thought to be authentic. The study concluded that the four coins, as appearances suggested, had been buried in soil for a substantial period of time, and were already deeply worn before their interment. This suggests that they had actually been in circulation in antiquity. It seemed possible from the first scientific analysis of a Sponsian coin that he could represent a real, lost Roman emperor.

The third century was a bad time for the vast empire, and it was a period that saw rapid, constant changes in political leadership. Between A.D. 235 and A.D. 284, there were at least 26 claimants to the title of emperor, mostly generals. When the Sponsian coins were first discovered, scholars thought they had identified a new emperor or usurper who had claimed the title in A.D. 249. But then 19th-century French numismatist Henri Cohen dismissed them as “very poor quality modern forgeries.” It didn’t help that no one had ever heard of Sponsian before. The case seemed to have been closed.

Pearson’s study, however, appears to have opened the discussion once again. “There’s been a lot of comments since we published the paper,” Pearson says. Responses have been posted online, he says, but nobody has “contacted me as the corresponding author with any serious critiques of the paper.” Pearson and his team hypothesize that the coins aren’t fake, and that they do indeed point to the existence of an otherwise unknown emperor.

Richard Lim, who teaches ancient Roman history at Smith College, says that the name Sponsian had never been on his radar. “There is such a long list of usurpers in the third century,” he says, “that even getting the names of all the emperors who were acknowledged as having actually reigned is a very trying experience.”

Lim found Pearson’s study well presented, particularly in its pushback against previous dismissals of the coins’ authenticity. Most compelling, he says, is the question of why anyone in the 18th century would bother making up an emperor. “Why would anyone do that as opposed to so many other kinds of forgeries that could have been attempted at that time?” he says.

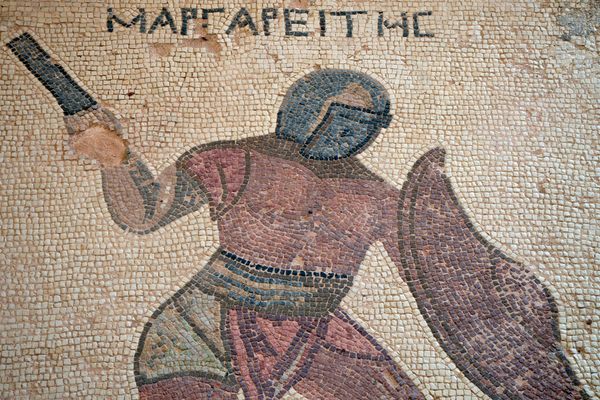

Even so, Lim is cautious about speculating on who Sponsian was, even if he did exist, on the basis of a few coins. The labeling on the coins, “IMP SPONSIANI,” he points out, doesn’t necessarily make him an emperor. “‘IMP’ stands for ‘imperator’ in English, but for the Romans, it meant a successful commander, which is what a victorious general would have been called by his soldiers,” Lim says. There’s not enough on the coins, he suggests, to formally crown Sponsian.

For Pearson, the publication of the study is just the first step. “It’s certainly true that there’s more to be done,” he says. “Ours was the first study of coins that are in Glasgow. There are others.” Pearson hopes to study a coin that is currently in Romania, in a similar condition as the ones in Glasgow. “What we hope to do is try to fingerprint the gold itself to a source,” he says. Pearson and his team hope the discovery will draw a little more attention to this period of crisis in the empire, and what leadership might have meant at the time. “I think it’s a really interesting period,” he says. “Whether our hypothesis turns out to be true or not, we hope it has stimulated debate and discussion about that period.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook