How Two Italians Achieved a 200-Year-Old Dream of Virginian Wine

Since Thomas Jefferson first tried, growing European vines had always failed.

Forty-two years ago, Gabriele Rausse received a phone call from a childhood friend who told him he had to “drop everything and come to America.”

The phone call was from one viticulturist to another. Rausse was 30 years old and working on a French vineyard. (He had been working in Australian wine, but his visa was revoked on a technicality.) His childhood friend, Gianni Zonin, was president of the Italian winemaking company Casa Vinicola Zonin. The two had grown up together in Italy’s Veneto wine region, and their phone call forever changed the U.S. wine industry.

Together, Zonin insisted, he and Rausse were going to establish the first Virginia vineyard to have commercial success growing Vitis vinifera, the species of grape responsible for fine wine.

“I was worried,” says Rausse. “All I could think was, ‘My God, he’s gone insane.’”

The year was 1976, and at that time, the idea of making premium wine in Virginia was crazy. While Napa Valley was establishing itself as a world-class producer, few had taken the idea of making European-style fine wine on the East Coast seriously since Thomas Jefferson tried and failed some 200 years earlier. The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services warned that vinifera varieties would not survive the winter. Even if they did, native pests and diseases would kill them off. According to wine-historian and journalist Richard G. Leahy, East Coast vineyards of the time made beverages that were almost universally “more relatable to winos than wine.” Crafted from French-American hybrids or native grapes that yielded flavors comparable to bubble-gum (think Boone’s Farm), the wines were essentially considered a bad-joke by connoisseurs.

On the call, Rausse debated how to tactfully turn down his friend. But he had a second thought.

“My only plan was to get my visa fixed and return to Australia. Suddenly, I realized going to America would let me practice my English,” he says. “So, I accepted. But with a big caveat. I told Gianni, ‘I’ll help you with your fool’s errand. But once I get my visa, I’m gone.’”

Zonin had considered establishing an American vineyard since visiting Napa Valley in 1961. He hoped to create a distribution center and further Casa Vinicola Zonin’s reach. He also worried that his family’s 11 vineyards might be nationalized by communists who seemed capable of winning elections in Italy. After inheriting the company presidency, the sixth-generation scion set out on a grueling survey of “every American viticultural region willing to build a winery.” After traveling to Oregon, New York, and California, he visited an Italian-born friend at the University of Virginia.

The visit coincided with the bicentennial of Jefferson breaking ground at his Monticello estate. Charlottesville was celebrating.

“I remember studying Jefferson’s attempts to cultivate vinifera in Virginia,” says Zonin. “I was fascinated by the idea of a president being a viticultural pioneer.”

Touring Monticello and the mountainous countryside surrounding Charlottesville, Zonin was reminded of his home in northern Italy. “It was so beautiful and somehow familiar. I was falling in love with the area,” he muses. He began to ask questions about soil, rainfall, and climate.

Then he learned of Jefferson’s enlistment of one of the 18th century’s most prestigious wine personalities, Philip Mazzei, an Italian, to manage his experimental vineyard. He also learned of Jefferson’s assertions that the venture would have succeeded if Mazzei’s vines had not been trampled by horses during the American Revolution. Says Zonin, “I began to think, ‘Maybe they chose this place for a reason.’”

Zonin returned to Italy, but Charlottesville stayed on his mind. In his spare time, he studied the region’s microclimate and traced the city’s latitude across the globe, comparing the data to that of sister regions in Italy.

“I noticed the average rainfall and temperature were nearly identical to areas in central Italy,” says Zonin. Virginia had long summers and mild, extended falls that often featured low rainfalls—ideal conditions for growing grapes. “That’s when I knew I wasn’t going to establish just another California vineyard. I was going to do this in Virginia.”

Rausse’s plane touched down in Charlottesville in early 1976. To his chagrin, he discovered Zonin had yet to buy a property. Over the next few weeks, they toured some 25 estates.

“They all looked very good. But Gianni kept saying: ‘No, this is not right,’” explains Rausse.

Then came Barboursville. The hilly, 900-acre estate dated to the 18th century and featured the ruins of an 1814 manor designed by Jefferson for his friend and political ally, James Barbour. Zonin took this history as a sign. Or, as Rausse puts it, “like we were being smiled upon by Mr. Jefferson.”

Though the purchase came as a relief, Rausse soon grasped the contentiousness of their project. “Everyone who knew anything about making wine was laughing at us, and doing it very publicly,” he says. “They didn’t just say, ‘Oh, this is silly.’ I believe they hoped for us to fail.”

Op-eds criticized them as buffoons. Locals cracked jokes about them being in the Mafia. An arsonist burned down the barn housing their winery. Farmers who had planted French-hybrid vines spoke out against them. Officials viewed them with suspicion—as if the endeavor were actually a ruse to undermine the East Coast’s so-called wine industry or mislead local farmers.

When Virginia’s commissioner of agriculture ascertained what was happening, he summonsed Rausse to a conference room in Richmond. For two hours, 24 scientists and professors took turns lecturing. Plant pathologists explained American diseases and virologists told of native viruses. One after another, they said Rausse would fail. The meeting adjourned with the commissioner pointing to a cigar box: “Tobacco is the real future of agriculture in Virginia, not wine.” A Virginia Tech professor added, “The moment you get a Virginia farmer excited about something that does not make any sense, we have a duty to step in and stop you.”

Rausse says he did not like being told what he couldn’t do. He decided he no longer cared about Australia. Walking the busy streets of the capital, he vowed to stay and make Zonin’s impossible vision a reality.

To make fine wine in Virginia, Rausse would have to solve three major problems: cold winters, virulent native pathogens, and late-summer droughts. Vinifera was particularly susceptible to all of these.

To combat occasional droughts, Rausse bought a bulldozer, affixed a huge red plow to its blade, and dug his furrows four feet deep. By creating a wicking system, he hoped to tap moisture from the deep, damp soil during dry spells.

To protect against pathogens and pests, he consulted with growers in the central Italian regions identified by Zonin. From them, Rausse learned about specific chemical sprays and techniques, as well as which vinifera varieties performed best at their highest elevations. These, he reasoned, would be more resistant to cold.

In search of more cold-weather solutions, Rausse researched American predecessors and experiments conducted around the world. A Virginian named Treville Lawrence, who had fallen in love with wine in France, was tending a half-acre plot of vinifera like a garden and had formed the Vinifera Wine Growers Association in 1973. He became an enthusiastic ally and friend, but he’d only so far managed to make a few bottles. So Rausse spent long days making phone calls to winemakers and looking in the library through microfilms of old magazines and newspapers.

Eventually, he discovered Ukrainian viticulturist Konstantin Frank, who immigrated to New York in 1951 and devoted himself to establishing vinifera. Approaching the task like a scientific experiment (he was a Cornell University researcher), Frank purchased a 100-acre homestead in 1958, and planted 66 varieties of vinifera. In 1962, he founded Vinifera Wine Cellars after producing a small batch of Riesling.

“When I discovered he had done this, I was so excited,” says Rausse. “I spoke to him as soon as I could.”

As the long-time butt of establishment jokes, Frank proved a willing conspirator. Based on his success growing vinifera in Ukraine and New York, Frank advocated grafting vinifera buds to rootstock from native vines. This provided two benefits. One, indigenous varieties were immune to native diseases and resistant to certain soil pests—such as phylloxera insects that preyed on tender young vines. Second, the roots would go dormant in the winter and cause the vinifera to do the same.

But there was a catch. Frank buried his vines to protect them from the harsh New York cold. In the spring, he’d dig them up. The process was costly and labor-intensive, and made profitable commercial-scale production unfeasible. Furthermore, it had a tendency to damage the vines. For Barboursville to succeed, its vines would have to survive on their own.

When Rausse cited the area’s winter temperatures, Frank got quiet. “It might just work,” he murmured. “Then again, you may lose everything.”

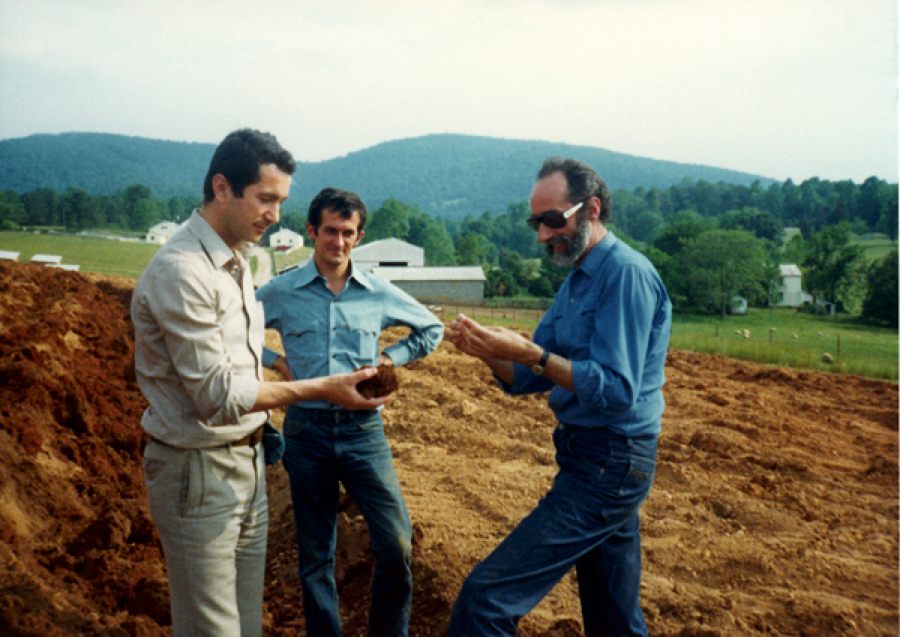

Undaunted, Rausse purchased 3,000 grafts from a Maryland nursery. He selected the Italian-recommended varieties and had them attached to the American rootstock suggested by Frank. Throughout the spring of 1976, he, Zonin, and a small team of Italians worked 14- and 16-hour days to plant them. Meanwhile, Rausse and Zonin bought cattle and sheep, hoping to offset the cost of the experiment. “That way,” says Rausse, “Gianni would not have to explain a total loss.”

As the vines began to grow, a renowned Italian viticultural professor paid a visit.

“He comes and inspects the vines and declares, ‘You will lose everything,’” recalls Rausse. The judgement was an unexpected blow. “Part of me was believing he would be impressed. That part was expecting to hear, ‘Look at what you have done, you are a genius!’”

Unfortunately, the professor’s warning proved accurate. By the end of the following winter, more than 60 percent of the vines had been killed by the cold. The rest were badly damaged. The experiment was a failure.

Though the catastrophe was hard to stomach, Rausse entered the spring of 1977 feeling more confident. During the previous summer, he’d seen the loss coming, and, in the process, made a discovery.

Rausse and Zonin had traveled to Napa Valley. There, they toured nurseries, looking to secure another source for grafted stock. Observing the plants and processes up close, Rausse was struck by an epiphany he describes as harrowing and extremely simple.

“I realized they were using a ‘V graft,’ which is very fragile,” he explains. “And mistakes they made during the heating process resulted in the callus [the tissue bonding the rootstock to the vinifera bud] being doubly weak … I knew then this would probably kill our vines.”

In California’s mild winters, the plants could recover. “But in Virginia, where the winters are much harsher, the graft has to be perfect. It has to be very strong,” says Rausse. “Otherwise, the plants will simply fall apart. And that is exactly what happened.”

Part inspired, part horrified, Rausse pulled Zonin aside. With no reliable source to provide grafts, they would have to make their own. Excusing themselves, the two booked the first return flight to Virginia.

Back in Charlottesville, they renovated an old greenhouse and constructed a nursery. Once again, Rausse hit the books. Digging into the past, he discovered grafting techniques employed by Russians to make wine in extreme northern climates. Combining those with what he’d learned working in northern Italy, Rausse devised a solution.

“We decided to use an omega graft, which is very strong and kind of resembles a puzzle-piece,” he says. “Also, we standardized the heating process.”

Tucking the grafted vines into a box full of wet peat moss, Rausse boosted room-temperature to 90 degrees and held it there for four days. This was followed by another 20 days at 80 degrees. The process allowed for the formation of a much tougher callus.

That spring, Zonin and Rausse doubled their plantings. The confidence proved justified. Their vines survived the winter and were, soon enough, producing grapes. Although the vineyard had not yet acquired the certifications for a commercial winery, Rausse produced a test batch of 500 bottles of Virginia-grown vinifera wine.

“I still remember that wonderful feeling when we harvested the grapes,” says Rausse. “I knew that we had done something very, very special. In fact, that same Italian professor called me and said, ‘By God, what you’ve done will change everything!’”

When word of the success began to circulate, orders for the miracle graft came by the thousands. In 1978 alone, he and Zonin sold more than 100,000 vines.

“The demand was unbelievable,” says Rausse. “We sold everything we had very fast and could not keep up.”Buyers flocked from up and down the East Coast, and they included three of the first Virginia wineries to follow in Barboursville’s footsteps: Meredyth Vineyards, Piedmont Vineyards, and the Oasis Winery.

Zonin and Rausse’s discovery effectively marked the beginning of Virginia’s fine-wine industry. Further, it proved vinifera could be grown on a commercial scale in traditionally inhospitable regions. The success quickly led to investment and advancements in New York, New Jersey, and elsewhere.

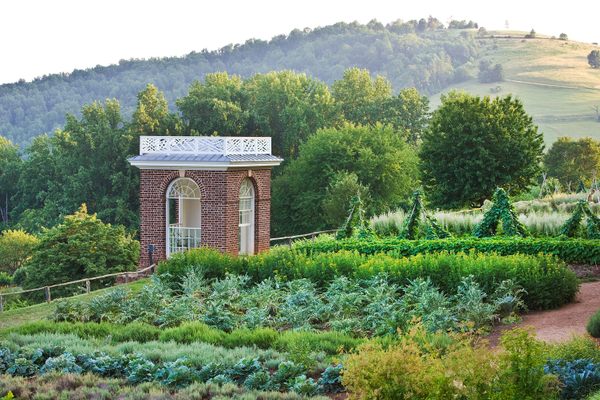

Today, of Virginia’s more than 280 vineyards, Barboursville remains the most esteemed and award-winning. Its Octagon vintage has played a crucial role in establishing the state as a world-class producer—most notably, when it was served at the 2011 wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton.

For this and other reasons, Wine Enthusiast named Zonin the recipient of its Lifetime Achievement Award in 2013.

Claiming the “most challenging and therefore most enjoyable work” was finished, Rausse left Barboursville in 1981, in favor of helping would-be entrepreneurs establish new vineyards. Since then, he has served as the primary consultant, planner, and orchestrating agent for more than 100 Virginia vineyards, and founded his own winery.

Of his achievements, Rausse is most proud of his work at Jefferson Vineyards where, in the early 1980s, he realized Jefferson’s dream of a Monticello vineyard.

“To me, Thomas Jefferson is the true father of Virginia wine,” says Rausse, standing on the Monticello hillside. Gazing down at the city of Charlottesville, his adopted home, he raises a glass of red wine. “I always toast to him. I say, ‘Mr. Jefferson, if it was not for you, I would be living in Australia!’”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook