Found: A Prehistoric Bead-Making Factory Town Off the Florida Coast

The kinds of beads they made were coveted far and wide a thousand years ago.

In 2010, two graduate students from the University of Florida landed on Raleigh Island, an uninhabited piece of Florida’s western coast, to check for environmental damage from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, which gushed more than three million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. They didn’t find oil, but amid the dense stands of palmettos and cedars there were dozens of large ring structures, where pre-Columbian people lived and ran a factory for making beads out of shells.

“They came back and told me and I was like, ‘Yeah, right,’” says Ken Sassaman, an archaeologist at the university and coauthor of a recent paper on the finds in the Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences. “‘Let’s check it wasn’t from some target practice range or mining work.’ Because there’s no precedent for it.”

Along Suwannee Sound, around 60 miles from Gainesville, the land fragments into a patchwork of islands and estuaries that are now mostly recreation areas and wildlife refuges that protect everything from manatees to black bears to bald eagles. Prior surveys had shown some signs of human presence on Raleigh Island, less than a mile from the mainland, but the scale of the site and its purpose were unknown until now.

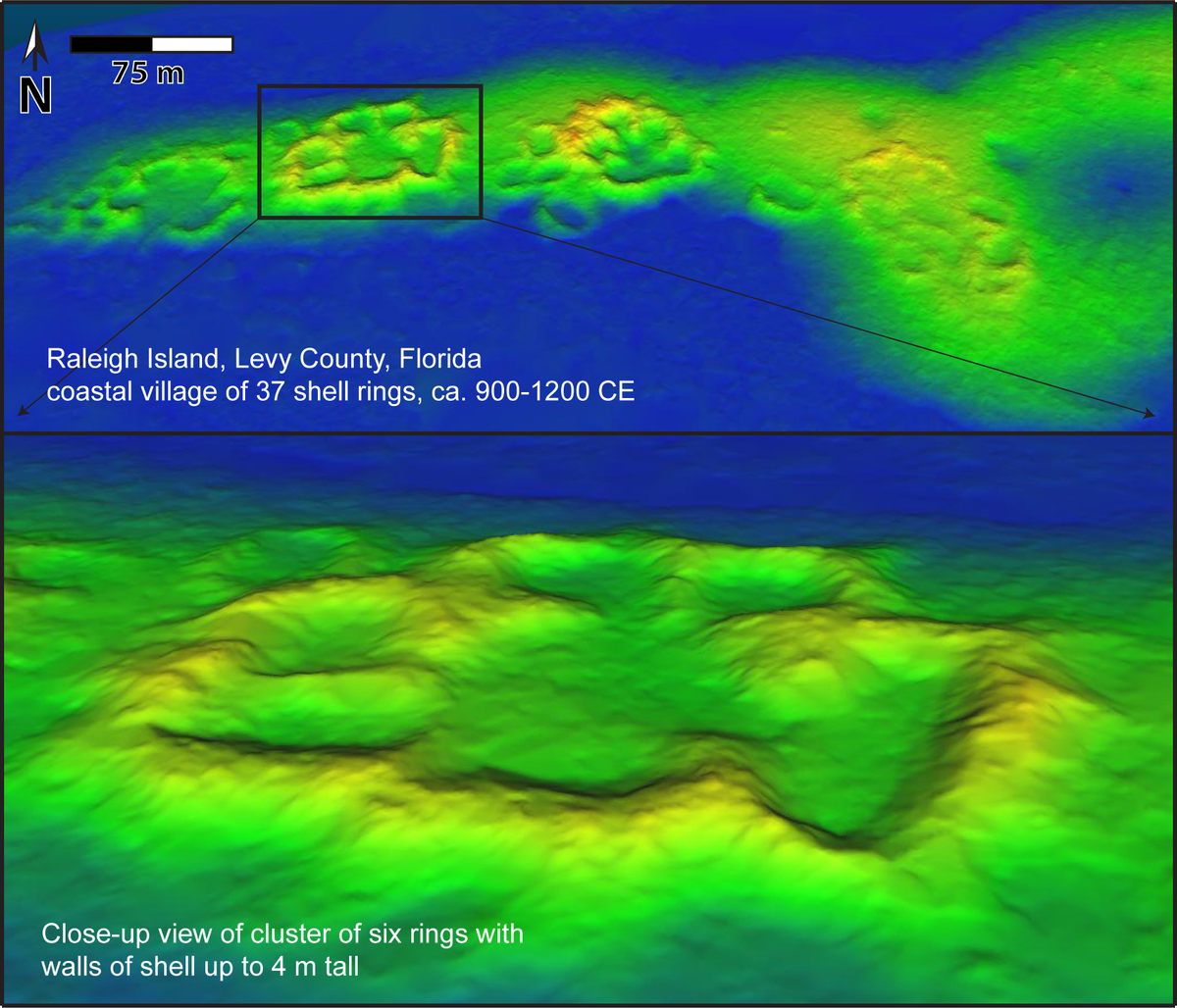

The University of Florida team used drone-mounted lidar equipment to survey the island’s topography below the dense foliage, and conducted test excavations. They found 37 rings of varying sizes, but each large enough to enclose a living space, some up to 12 feet tall, and all made of discarded shells dating to between 900 and 1200.

“[The site] is unprecedented in terms of form, but we were also surprised to find it was as late as it was,” Sassaman says. “Architecture like that—rings—were pretty common in the southeast 4,500 years ago, but nothing like Raleigh. Everything was surprising, everything was unprecedented.”

Each ring had lots of oyster shells, but also evidence of the making of beads from marine snail shells, mostly lightning whelk. The scale of the site suggests that it was a major production area for the beads, though archaeologists found fewer of them than they had expected.

“We have a lot of evidence, all that you’d need, that they’re making a pretty substantial amount of beads,” says Terry Barbour, a doctoral candidate at the university and lead author of the study. “[But] we don’t have a whole lot of finished products. Just bits and pieces, enough that there should be substantial amount of finished product.”

Researchers suspect that the finished beads may have been collected for trade. Shell beads like these would have been of great value as far inland as the major cultural centers of Cahokia (where 25,000 of them were placed in a single grave) near modern St. Louis, and Moundville, near Tuscaloosa, Alabama. They were used in bartering, art, and gambling, and also carried symbolic value, as the lightning whelk was associated with the sun.

“Demand is huge right after the rise of Cahokia,” says Barbour. “Marine shell has waxed and waned for the past 12,000 years of history and in the Mississippian [culture period], things reach the highest they ever did. We happened to find a community that’s right there at the source.”

Though Raleigh is now only inhabited by raccoons, rattlesnakes, and some rampant feral hogs, one can kayak the marshy environs and marvel at the industrious effort of the island’s pre-Columbian residents.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook