The Gnarled History of Los Angeles’s Vineyards

It was once known as the “city of vines.”

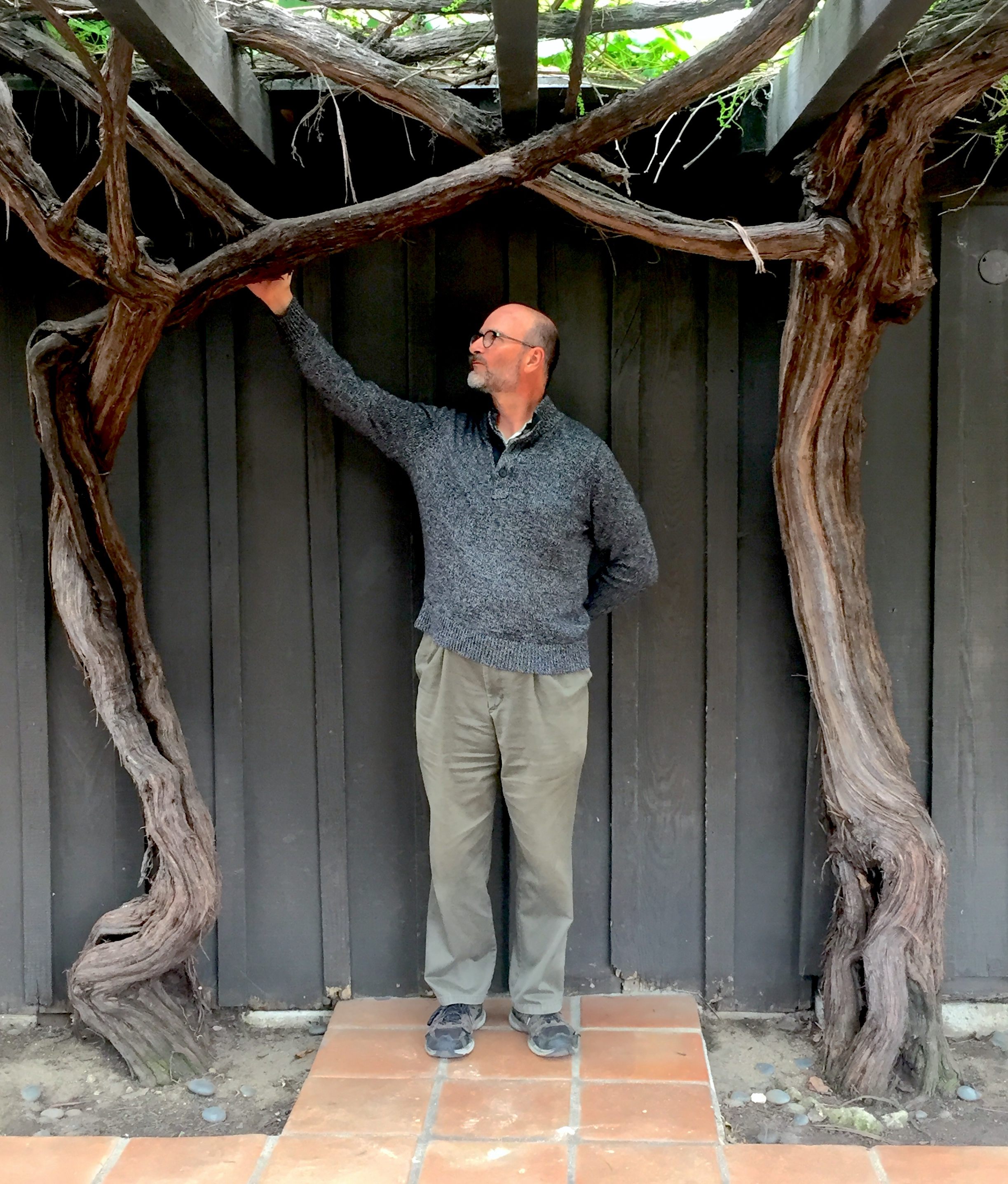

Mike Holland, a bespectacled home winemaker, often arrives downtown several hours before starting his day job, at the Los Angeles City Archives. Before the sun rises over the Avila Adobe on Olvera Street— built in 1818, and considered to be the oldest home in the city—Holland will perch on a ladder pruning, trimming, and managing a tangle of leaves. His goal is to gather as many of these minuscule grapes as he can before 9 a.m., the Adobe’s opening time.

These aren’t your ordinary vines. Years ago, Holland, whose office is located near the Adobe, had been taken with these unusual vines, which lurch skywards and through a main artery in the building. He was curious, and offered to care for them, and make wine out of them. To find out more about their origins, he sent cuttings to the Foundation Plant Services at the University of California, Davis, whose staff came back with astonishing news: The vines were a hybrid between a local grape and a European grape, and they genetically matched what’s now known as the Viña Madre, or the “mother vine” grape that grew at the nearby Mission San Gabriel.

That meant that Holland had stumbled upon a relic, a vine that was perhaps the first in California to produce grapes to make wine. Since then, Holland has been using these grapes to make a special sherry-like wine, called Angelica, that has its origins in Southern California, too. It’s one of the sole remnants of a time when vineyards covered downtown Los Angeles.

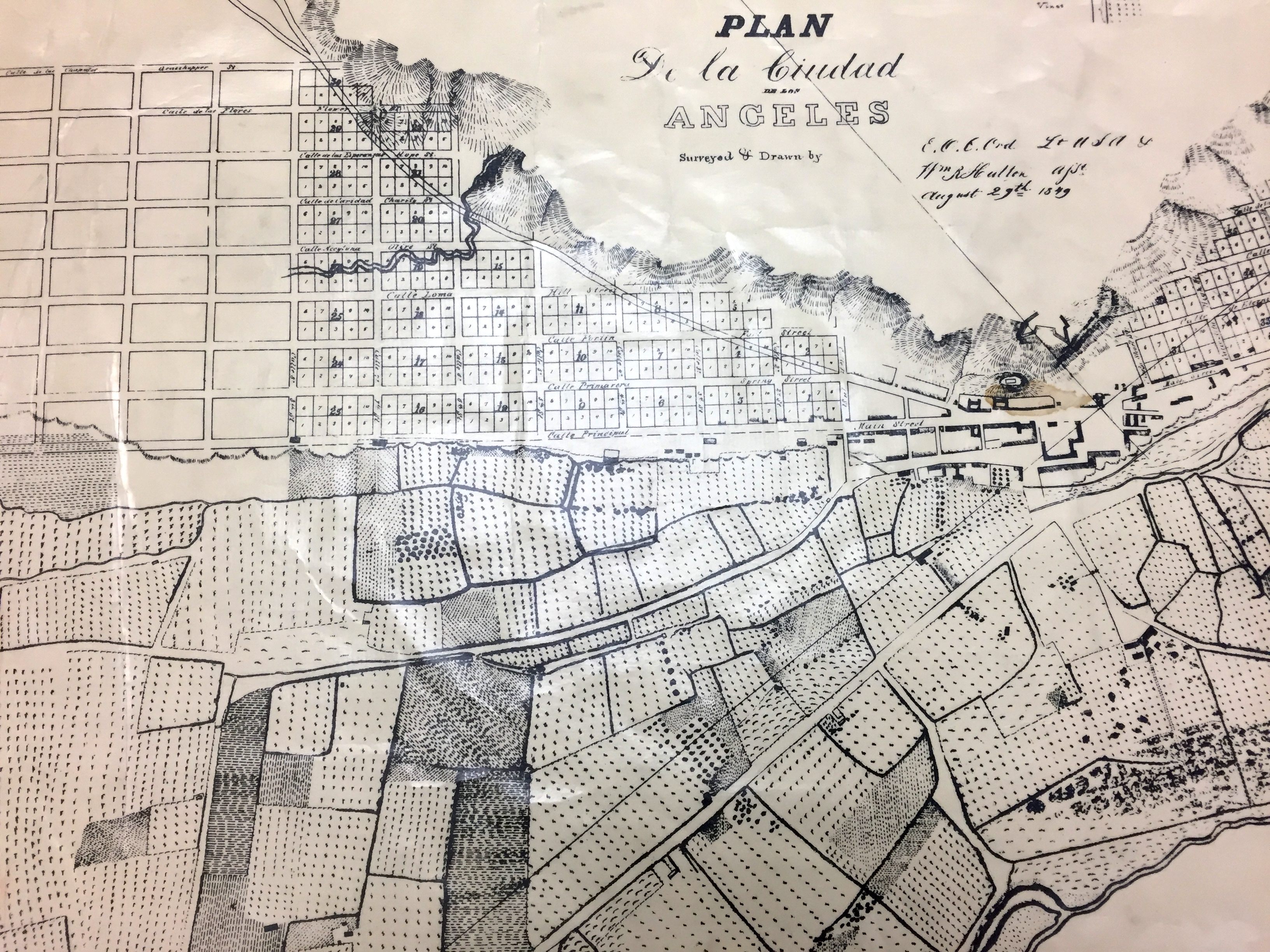

Long before a maze of highways spliced through the city—preceding the cluster of gleaming skyscrapers that tower above downtown, as if making eye contact with the mountains—vineyards enveloped the now-urban center. Throughout the 19th century, many acres of grapevines grew right where contemporary landmarks, such as the Bradbury Building (seen in many films) and the Angels Flight now stand. Back then, Los Angeles was not only the birthplace of California wine country, but its beating heart, too.

Before California even became part of the United States, it was Los Angeles—not Sonoma, not Napa—that was poised to become the winemaking epicenter of the west coast. So much so that by 1850, the Los Angeles area boasted over 100 vineyards, and the city’s first-ever seal, drawn up several years later, dubbed it the “city of vines.” So how is it that L.A.’s northern neighbors won California’s winemaking crown, while the city’s own history as a land of vines faded into obscurity?

“It’s more of a tale of urbanization, unfortunately,” says Steve Riboli, who helps oversee winemaking operations at San Antonio Winery. Built in 1917 by Riboli’s great-great-uncle Santo Cambianica, an Italian immigrant, San Antonio is the last surviving downtown Los Angeles winery. The timing was unfortunate—as it was built three years before Prohibition—but a local church allowed Cambianica to make sacramental wine, one of the loopholes during that dry era. “We were able to survive because he was a very devout Catholic,” Riboli says.

Before then, basement to full-fledged operations flourished in the area. But continuous population booms, especially during the Gold Rush era, both helped build and ultimately ended L.A.’s winemaking prospects.

The city’s history as a wine town started when California was colonized by the Spanish. Spaniards enjoyed drinking wine and Franciscans used it in religious ceremonies. One of the missionaries sent there, Father Junipero Serra, had grape cuttings sent up from Mexico in 1778 and began to produce sacramental wine. The vines thrived at Mission San Gabriel, a skip away from present-day Los Angeles.

Around then, wine production in Los Angeles began picking up. Winemaking wasn’t a commercial prospect for the region until a Frenchman, Jean-Louis Vignes (whose last name means “vines”) immigrated there. As journalist Frances Dinkelspiel writes in her book Tangled Vines: Greed, Murder, Obsession, and an Arsonist in the Vineyards of California, he was the first “to recognize there was a market for wine outside the Los Angeles area.” Along the Los Angeles River, he built a stately, 104-acre vineyard that soon attracted visitors who wanted to drink and socialize there.

But Los Angeles’s winery days came too early to enjoy wide acclaim. “It was such bad wine for such a long time, and California was always trying to convince the East Coast to buy its wine, and not French wine,” says Dinkelspiel. “It took a really long time for people to be interested in buying California wine.” Americans were also far more partial to beer, and shipping was challenging. Even in the 1850s, California was still so isolated that residents were begging the government to build highways.

But in 1848, the Gold Rush hit. Many people who came looking for gold found themselves growing grapes. In her book, Dinkelspiel cites a journal of the time, the California Farmer and Journal of Useful Sciences, which informed farmers that they could rake in $200 per acre if they planted grapes. Coupled with a tax break from the California Legislature, it’s no wonder that the number of grapevines in the state swelled from just over 324,000 in 1855 to over 4 million just three years later. Soon, vines covered Los Angeles County, at least from Malibu stretching past Pasadena.

“By about 1870, when this area was starting to go through its first urbanization, that’s when the landscape started to change,” says Holland. “Once the railroad hit in 1875, the floodgates opened.” Los Angeles suddenly became a sizable city: In 1870, its population was 5,728, and by 1890, it had ballooned to over 50,000 residents. Part of that influx came from what a swarm of investors flooding the state, around the time a disease named phylloxera knocked out scores of European vineyards. “A lot of capital from England and around the world came to Southern California to try to take advantage of [it],” says Dinkelspiel.

But Northern California began developing, too. “They actually started vineyards there and started to make their wines locally,” says Holland, “So they didn’t need it brought on trains to San Francisco.” Worse, a strange ailment known as Anaheim Disease (later dubbed Pierce’s Disease) started to cause Los Angeles’s grapes to wither, then the roots to die altogether, starting in 1883. “Anaheim Disease, with its destructive and rapid rush through the vineyards, signaled the end of Southern California’s dominance in the wine industry,” writes Dinkelspiel. By 1890, Northern California had far surpassed its southern neighbors in winemaking production. Some former winemakers began planting other crops, such as oranges, instead.

That too came to an end with the last haul of urbanization in the 20th century. “When the aqueduct brought the water in from Owens Valley 200+ miles away in 1913, that’s when everything changed,” Holland says. “It went from being a small city to a big city, expanding and exploding and redefining itself ever since.” The post-war population sent land values skyrocketing, and the last of the vineyards were ripped out. “[During] that time period, the 1800s through the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, housing was just taking over everything downtown,” Riboli says. “So that’s what really destroyed the industry.” Soon enough, the only known vines in Los Angeles were the survivors clinging to old buildings, such as the grapevines Mike Holland found on Olvera Street.

Despite winemaking’s rich history in the region, there’s been little effort on Los Angeles’s part to reclaim that part of its identity. It may have to do with the industry’s dark past: Missionaries and winemakers alike essentially enslaved local Native Americans for their labor.

The mission system set up by the Spanish had drawn or conscripted many Native Americans to live there. They were lured by talk of Christianity, or were seeking shelter during a time of environmental change and disease. Upon Baptism, though, the Spanish controlled their lives and forced them to work the fields. When the missions disbanded after Mexican independence, they couldn’t go back to their land. So they went around Los Angeles in search of work.

But, as Dinkelspiel writes, one of the the first acts of legislation passed by the newfound state of California, in 1850, was the Indian Indenture Act. The law forbade Native Americans from voting, and allowed them to be arrested on the spot for not working or for appearing drunk. Native Americans would be arrested on weekends. When they were released from jail, their labor was sold to the highest bidder, often a grape farmer. “At the end of the week, the vineyardists or farmers would pay two thirds of the fine to the city and the rest to the Indian worker—in high-alcohol aguardiente, ensuring the cycle would be repeated,” she writes. That cruel cycle lasted until 1862, when the California Legislature repealed the act.

The wounds of this ugly history still resonate today, and is “something we have to do some reconciliation with,” Holland says. While Dinkelspiel says that these abuses are not yet widespread knowledge, “there is this gradual shift in public reception,” thanks to more information being released and acknowledged.

Though winemaking itself remains a side note in Los Angeles’s history, and one that’s not lauded due to the history of exploitation, its agricultural past and origins in viticulture remain curiously immortalized at the city’s most famous intersection: Hollywood and Vine, the symbolic crossroads of its two most influential industries.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook