An Investigation Into the History of the ‘Ditz’ Voice

How pitch, tonality, and celebrity imitation have portrayed cluelessness.

In January, Saturday Night Live aired a sketch spoofing The Bachelor, one of many they’ve done throughout the reality juggernaut’s time on air.

Bachelor contestants adhere to a long-established archetype in the public consciousness: the vapid gold-digger who needs a man to make her life complete. Most of the cast members depicting the contestants adopted a certain speaking style: monotonous, with elongated ending syllables and a lot of vocal fry, in line with the voice associated with “ditzy” girls today. But host Jessica Chastain’s interpretation was slightly different: her voice had a higher pitch and a little more musicality—more AMC than ABC. Though it sounded old-fashioned, it was clearly recognizable as part of a library of voices women have pulled from over the years to play silly, sappy, or simpering women.

A version of this voice has existed since sound met film and, in a way, since a little before that. Actresses of early film played mostly damsels in distress or wide-eyed young women, and by the time talkies took over, women were still portrayed as less headstrong, more head-in-the-clouds. “The 1920s had a serious case of the cutes,” notes Max Alvarez, a New York-based film historian. “There is a prevalence of childlike women in the popular culture [at the time] … Girlish figures, girlish fashion, girlish behavior.” Along with these girlish figures came a girlish voice—high-pitched, a bit breathy, and a little bit unsure, evident in Clara Bow’s pouty purr, and even Betty Boop’s singsong.

Shortly after the advent of sound in cinema, the scrappy, spunky flappers of the ‘20s were relegated to supporting characters—“the gangster’s moll, the cocktail waitress,” says Alvarez. Musicals of the era, says Alvarez, were bastions of these kinds of wise-cracking wacky sidekicks. “Anything with a backstage Broadway setting, you’re gonna find these women.” The speaking voices filling these film’s chorus lines were still childlike as in the decade prior, but started to show signs of the modern-day “sexy baby voice”: a little bit breathy, a little bit nasal, and with fewer harsh consonant sounds.

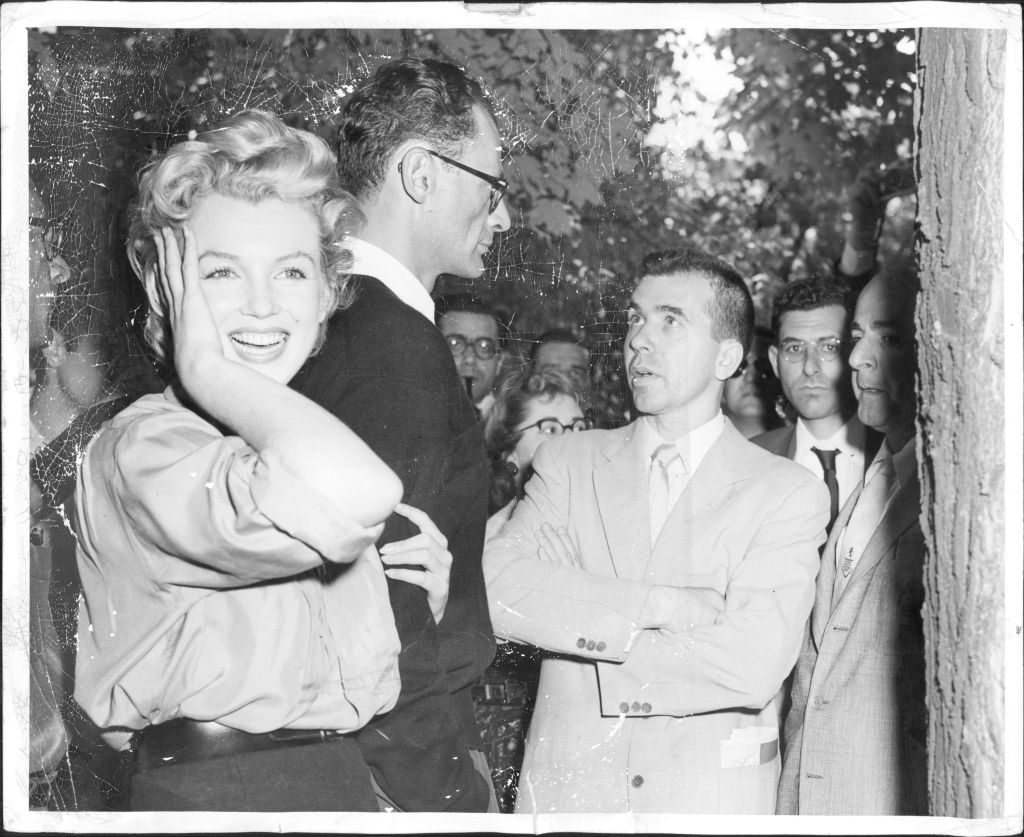

Leading ladies like Katharine Hepburn and Lauren Bacall portrayed feisty women through deeper voices as America entered the Rosie the Riveter era. It wasn’t until the 1950s, when women were less vital in the workforce, that softer voices took center stage again. And boy, did they ever. “We think of blondes as being dumb because we tend to think of Jean Harlow and Marilyn,” says Alvarez. Though Marilyn was famously influenced by ‘30s screen siren Jean Harlow, her bubblier, breathier speaking style—most notably, her immortal rendition of “Happy Birthday”—still have a stranglehold on the voices used to denote “sexy, but not very smart.”

Actresses like Ann Margret and Jayne Mansfield propagated it well into the ‘60s. The higher pitch that had been the standard for “silly” hung back as the sexual revolution took hold, though it could still be heard in performances like Goldie Hawn on Laugh-In. Things hadn’t improved much by the 1970s. “The women’s movement has no impact on Hollywood because the films are all about male angst,” says Alvarez. TV wasn’t much better—though stars like Farrah Fawcett kicked ass on Charlie’s Angels, they mostly still spoke in disarmingly high, soft voices.

The unnaturally high pitch used over the years is all a diversion tactic, says Professor Emeritus of Linguistics at UC Berkeley, Robin T. Lakoff. Sounding “masculine” often invites ridicule, so, whether they do it consciously or subconsciously, these hyper-feminine, childlike voices and mannerisms associated with un-serious women could be the result of them over-correcting to stave off criticism. “‘I don’t want you to think I’m hard,’” is what Lakoff says motivates this. “Aiming at the ‘S’ [sound] and hitting it is harder than if you put your tongue a little back.”

It’s also important to note that the actresses cast as wisecracking sidekicks or tawdry sex maniacs were generally savvy and intelligent in real life. “Many of these women … had to be adults at a very young age,” says Alvarez. Many early film stars came from working-class backgrounds, sent to support their households once their parents saw their talent. Mary Pickford was a whip-smart dealmaker in Hollywood, says Alvarez, but was constantly cast as “an annoying, childlike waif.” Marilyn Monroe famously attended the prestigious Actor’s Studio to hone her craft, and Gloria Grahame, typecast as a sex kitten in the ‘40s, was the child of a British stage star who trained her in the traditional style.

The voice we now recognize as “ditzy”—the one that permeated the Bachelor sketch—gets its start in the “Valley Girl” vocal trends of the ‘80s and ‘90s. The Valley Girl voice is more natural, but still balanced with Monroe’s eager-to-please disposition, resulting in the much-derided “upspeak”—the tendency to end sentences on a higher intonation, the way American speakers do with questions—and the guttural buzz made by dropping the voice to the lowest register, called the “vocal fry.”

“I don’t understand why people worry,” says Lakoff of the panic that crops up every decade or so over changing speaking patterns. The voice we associate with dim, dull, and ditzy women has evolved, but it’s all coming from the same place: It’s a way to deflect potential ridicule by asserting—sometimes aggressively—femininity. “A lot of the times it isn’t that women said, ‘Okay, I don’t have to carry this baggage around with me anymore, I’m gonna talk [in a way that’s] natural, but instead they substituted one form of girliness, ladylikeness for another,” says Lakoff. Though Kim Kardashian’s vocal fry is a far cry from Marilyn Monroe’s breathy lilt, the aim is still the same. “What people will not want to hear is it’s still with us,” says Lakoff. “[They] still wanna please and [they] don’t wanna frighten.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook