All Winter, These Ants Make the Ultimate Sweet Sacrifice to Their Colony

Their syrupy death is medicinal for humans, too.

Prepping for winter requires serious effort. By the time autumn falls brisk and wet, tree squirrels are already hard at work hoarding and hiding the nuts and seeds they’ll need to sustain themselves through the coldest months. Moles are busying themselves capturing and immobilizing earthworms in underground dungeons. And acorn woodpeckers are drilling and storing up to 50,000 acorns in the dead limbs of “granary trees.”

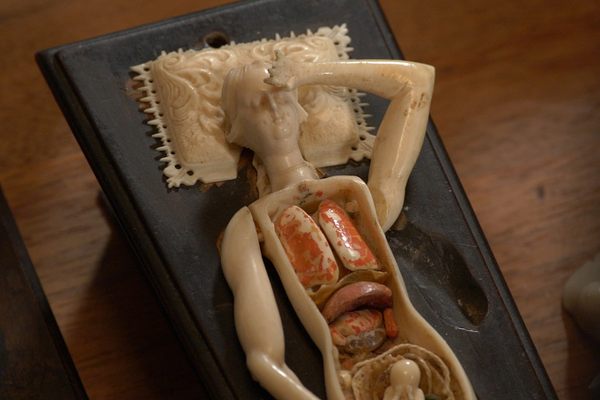

But while many creatures build some version of a food pantry that will keep them fed through the harsh wintertime, only honeypot ants store their food in living, breathing vessels. When frigid temperatures lead to scarcity above ground, a select group of the ants, abdomens swollen from a season of consuming nectar, keep the colony fed with their vomit.

Around 1,000 ants out of 5,000 in a honeypot colony are conscripted into the sacrificial profession. Like grotesque storage containers, these “repletes” hang largely immobile from specially constructed chambers, explains John Conway, biology professor emeritus at the University of Scranton, who studied Myrmecocystus colonies endemic to desert-like regions of the American Southwest and Mexico. When the cache of rich liquid in their abdomens comes to an end, so do their lives.

Many honeypot ants are filled with the nectar collected from flowering plants and the “honeydew” secreted by aphids, but they aren’t the only fluids contained in the valve-controlled digestive tract of a replete. “Most are a golden to dark golden color, but there are a few of them that are also milky in color, and some ants are clear,” says Conway. “Some of them, we think, store water, and some may store dead insects brought into the nest.” Together, the repletes form a complete nutritional smorgasbord.

The repletes in North American honeypot ant nests aren’t born that way. Entomologists believe that they hatch as worker ants then self-sort sometime later. While the largest worker ants tend to be those that later develop the swollen abdomens, small workers can also make the transformation—though researchers aren’t exactly sure why. No one, says Conway, has yet been able to prove whether there’s “some kind of anatomical peculiarity” that predisposes some ants to the role while leaving others to live as workers.

Whatever the reason, the phenomenon appears to cross species and continents. Ants belonging to entirely different genera—six of them across the world, including in Africa and Australia—appear to researchers to have almost identical physical and behavioral traits. Each group has a population of swollen repletes that regurgitates to feed the nest at times of food scarcity.

“It’s a perfect example of what we call convergent evolution, the formation of the same adaptation to the same environmental conditions,” says Conway.

One of the most prominent species outside North America is Camponotus inflatus, which calls Western Australia home. Like Myrmecocystus, Camponotus lives in dry, desert-like conditions where temperatures drop in the winter months. Like Myrmecocystus, they’re referred to as “honeypot ants.” And like Myrmecocystus, their repletes don’t only feed their colonies during times of scarcity; Indigenous communities in both regions have harvested nectar-swollen honeypot ants since time immemorial.

“Traditionally, it was the women only who would find the honey ants and dig for them,” says Danny Ulrich, a member of the Tjupan language group whose family runs Goldfields Honey Ant Tours in Kalgoorlie, Australia. Ulrich describes the ants as sweet like molasses with a “very slight tangy taste” that comes from the formic acid they excrete when in danger.

Observations made by researchers in North America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries suggest that honeypot ants were similarly enjoyed by Indigenous people on the other side of the world. Journalist Peter Lund Simmonds even saw repletes being sold fastened to squares of paper in Mexico City markets, which he wrote about in 1885, noting that their “honey” was sometimes fermented into an alcoholic spirit.

Although these days the Tjupan only consume the ants as a treat, the thick, syrupy substance was traditionally used to soothe sore throats or “topically on cuts and abrasions to keep infection at bay,” says Ulrich. Historical accounts suggest that North American tribes also used honeypot nectar medicinally, although Conway’s “been unable to find much definitive info about it.” Earlier this year, microbiologists came up with a scientific explanation as to why the remedy is an effective one: Honeypot ant nectar fights some bacterial and fungal infections with its unique antimicrobial and chemical properties.

Ulrich wasn’t surprised by the results of the study, for which he had helped the researchers locate a honeypot ant nest at the base of a mulga tree in Western Australia. This is not the only region where Western medicine is just now discovering the secrets of nature that Indigenous communities have known all along. “It’s truly a blessing [to] follow in the footsteps of our ancestors,” he says. “We never take more than we need from the honey ant nests, we always make sure there is enough left for the ant colony.”

That restraint is essential to the survival of the species, especially because Conway’s recent research indicates that in Colorado, at least, honeypot ant colonies seem to be rapidly disappearing. Between his first study at the Garden of the Gods in Colorado in 1975 and a survey he conducted there in 2018, the number of nests in the park had declined by 58%.

“I suspect that, just like every place else, climate change is affecting them to some degree,” Conway says. Increased tourism in the park and development nearby are likely also playing a role. One research site he studied in the 1970s has since been turned into housing.

But Conway found something else unexpected, too. Eight of the nests he’d studied 43 years ago were still there. Although there’s no way of knowing if the same queens have been ruling their subjects all that time, “if that’s not a record of nest longevity, it’s close,” he marvels. It’s just one more surprise from one of nature’s most winter-resilient insects.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook