How Georgia’s Winemakers Went Underground to Survive Soviet Occupation

The world’s most ancient winemaking culture almost disappeared.

When Illia Kiknavelidze made wine in the Republic of Georgia, he had to lower his entire body into human-sized clay pots, called qvevri, that were buried underground. Using the rough bark of a cherry tree, he would scrape the inside of each egg-shaped pot by hand, removing every bit of grape skin and bacteria from the previous batch. Every inch had to be immaculately scrubbed to keep the next round from spoiling. Then, he would fill his qvevri with juice from local grapes, cover it, and let nature do the rest, just like local winemakers had been doing for some 8,000 years.

Qvevri are cultural metaphors, writes Keto Ninidze, Kiknavelidze’s great-granddaughter and a Georgian winemaker, in an email. Much like how someone might give birth to a child, she says, qvevri give birth to wine. And after many years of giving life, the qvevri were used as a burial place. “So in Georgian cultural perception, [qvevri are] regarded as the cycle of life and death,” she says.

Georgia has the oldest wine culture in the world, and little changed from the earliest qvevri to Ninidze’s qvevri. Everything—down to the shape of the clay pots, the method of burying the qvevri, and letting crushed grapes ferment naturally inside—is passed down from generation to generation. When the Soviet Union took control of the country in 1921, this ancient winemaking tradition was pushed underground, where it almost disappeared. During these years, Georgian winemakers lost their land or had to give over all of their grapes every harvest. If they wanted to make their own wine, they’d have to forage grapes from wild vines on hillsides, in forests, and sometimes on the sides of village streets.

Before the Soviet Union imposed their rule on Georgia, though, more than 500 different grape varieties flourished in the country’s moderate climate, tempered by its proximity to the Black Sea. Thanks to the environment, wine grapes grow without much intervention. Back then, most grapes were picked by hand and crushed by foot. The juice, skins and stems and all, were then put into qvevri.

Emily Railsback, the filmmaker behind the Georgian wine documentary Our Blood is Wine, saw qvevri sizes ranging wildly: Some pots were too small to scrub inside, while others could fit several people (a capacity of 10,000 liters). The size of qvevri depended primarily on the region; western Georgia traditionally has smaller pots than eastern Georgia. Either way, all of them are buried at least partially underground, where the temperature is consistent year-round. Once a qvevri is put underground and buried, it is never moved.

For around six months, natural yeasts ferment the juice inside the pots. The solid parts of the grapes filter the liquid, which funnels naturally towards the bottom. Once fermentation is over, the wine is suctioned or scooped out and bottled. Or, more likely, it’s stored in smaller pots. Then the cleaning process begins. The tools of the trade have upgraded, Ninidze says, and winemakers now wash qvevri with high pressure water, ash, and citric acid, then disinfect the vessels with sulphur smoke. What hasn’t changed is the immovability. Qvevri is “something you can’t take from one place to another,” Ninidze says, adding that once a winemaker chooses a spot for their qvevri, they’re rooted there until they pass it on or buy new qvevri.

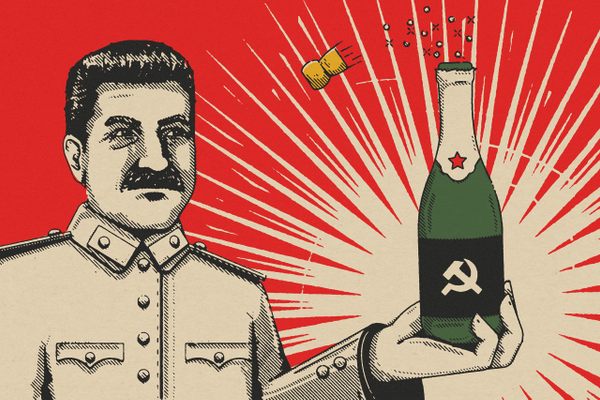

This process didn’t budge for years. Then, the Soviet Union invaded and annexed Georgia in 1921. The slow, natural qvevri cycle—an extension of the Georgian lifestyle—didn’t fit Joseph Stalin’s five-year economic plans. These plans set economic goals and called for industrializing industries, including wine. Rural winemaking would need to be mechanized, and the wild-looking vines would need to be tamed. In the region of Kakheti, officials uprooted more than 500 native varieties. Steel tanks replaced the storied underground clay pots, too.

The government then redistributed and repurposed the annexed land previously used for wine, and built sterile buildings on top of them. “You see these Soviet buildings everywhere that are sturdy cement and nothing beautiful about them, but very practical,” Railsback says. “And then the Georgian [buildings] are more beautiful, and the architecture is really unique with hand-carved woodworking on the front of houses. There’s the Georgian look, and there’s the Soviet [look] that tried to demolish the culture and vibe—you feel that literally everywhere.”

During that time, families were given a single acre of land compared to the full vineyards they once tended to alongside their homes. Vines were ripped out and replaced with tidy rows of hardy, high-yielding varieties such as Saperavi and Rkatskeli. While they were plentiful and certainly sweet, they were bland and lacked the character of traditional Georgian vines. “There was one or two state factories that [processed] the whole yield of the country,” Ninidze says. “The production policy was of course industrial (especially after Stalin’s period), based on the five-year plans and neither the factories nor the farmers cared [about] the quality of the grape.”

Any sort of scale in qvevri wine-making was gone, too. Home winemakers grew vines around their home and foraged from vines that were available. While it wasn’t illegal to make qvevri wine during this time, it had to be done during people’s spare time. There was no money in qvevri wine, so there was no a financial incentive to make new qvevri, either.

By the 1980s, more than 440,000 tons of commercial wine was made in Georgia every year, most of which went to Russia and Georgian cities. Virtually none of it was made in qvevri. But in the countryside, qvevri survived in people’s basements.

Ramaz Nikoladze’s family are some of these industrious winemakers. His earliest memories are of helping his father crush grapes and clean clay, and making wine under the Georgian sun with decades-old qvevri. His great-grandfather, Mina Nikoladze, purchased a winery and made wine before the Soviet era. That land was taken from him, but he continued to make wine at home with his sons. Those sons did the same with their sons, a practice that eventually trickled down to Ramaz. These days, the 44-year-old is an influential Georgian winemaker.

“From childhood, my father had the qvevri, and he always made the wine in qvevri,” Nikoladze says. “We never stopped making wine in qvevri.” Nikoladze estimates that there are qvevri at least 100 years old in perfect condition on his father’s property—meaning they date back even before the Soviet era. The infrastructure to keep qvevri tradition alive was always there, passed down through families just like winemaking knowledge.

It’s hard to know exactly how many people passed on winemaking traditions like Nikoladze’s family did, partially because domestic production wasn’t recorded. Nikoladze says that his family was one of a few making wine in his village of Imereti when he was growing up, and the others also used their father’s or grandfather’s equipment. Nevertheless, when Railsback traveled to Georgia for her film, she found that nearly everyone that she and her crew met knew about someone crafting qvevri in their basement. Everyone knew someone who knew someone, and qvevri wine managed to get around. That’s because, Ninidze says, “society trusted homemade wines much more than the wines made in a factory.”

But without any means of serious production, you could hardly say that qvevri wine was thriving under Soviet rule. The first major change to the wine dynamic happened when the Soviet regime collapsed in 1991. Civil unrest hit Georgia soon after, as the country adjusted to being an independent state. Wine production decreased tenfold, according to Al Jazeera. Still, around 80 percent of Georgian wine went to Russia, simply because there was no demand for the wine made in the Soviet style elsewhere. Then, Russia dealt another blow to Georgia’s wine producers in 2006 when President Vladimir Putin’s government banned Georgian wine imports. The ban was allegedly enacted for safety concerns, but the timing lined up with a Georgian push for the pro-Western policies of then-president Mikheil Saakashvili.

With the Russian market gone, Georgian winemakers needed to appeal to Western consumers, and industrial wine wasn’t going to cut it. But qvevri, with its history and its natural, small batch production, could. Producers were no longer so commercially restricted, and there was opportunity for a new business. That’s how, in 2004, Nikoladze was able to purchase his grandfather’s farm, which had been taken by the Soviets, and start bottling qvevri wine there. While the ban was economically devastating, it provided a catalyst for new winemakers to thrive, too.

Then in 2013, UNESCO designated Georgian qvevri winemaking as an intangible cultural heritage. Russia lifted the Georgian wine embargo that same year. Qvevri wine today is only around one percent of the total Georgian export market, but interest, particularly from the West, is growing by the day.

“For people who grew up drinking conventional wines, it may take some convincing,” says Amanda Bowman from Chambers Street Wine in New York. “Qvevri wines aren’t always polished. And some people are still skeptical about the merit of wines made without modern technology and wines without score points. But qvevri wines are already in demand.”

Most of the qvevri wine coming out of Georgia these days is white. Since it’s aged on the grape skins, it takes on a slightly more orange hue and has more body than a typical white wine, with high acidity and a tanginess. It helps that the natural wine movement is on the rise, and as people start to gravitate toward more tart wine, those made in qvevri have been a welcome addition to wine rotations.

In Georgia, Railsback sees more economic opportunity to make qvevri wine for the local market as well. Qvevri bested the Soviet Union’s collectivization plans. With that kind of survival story, the world’s oldest winemaking method merits protection and preservation alike. “This is my wine,” Nikoladze says. “This is my blood, this is my all that I have because [I spend] every day, every time, every minute working in my vineyard.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook