How Unions and Regulators Made Clothing Tags an Annoying Fact of Life

A brief history.

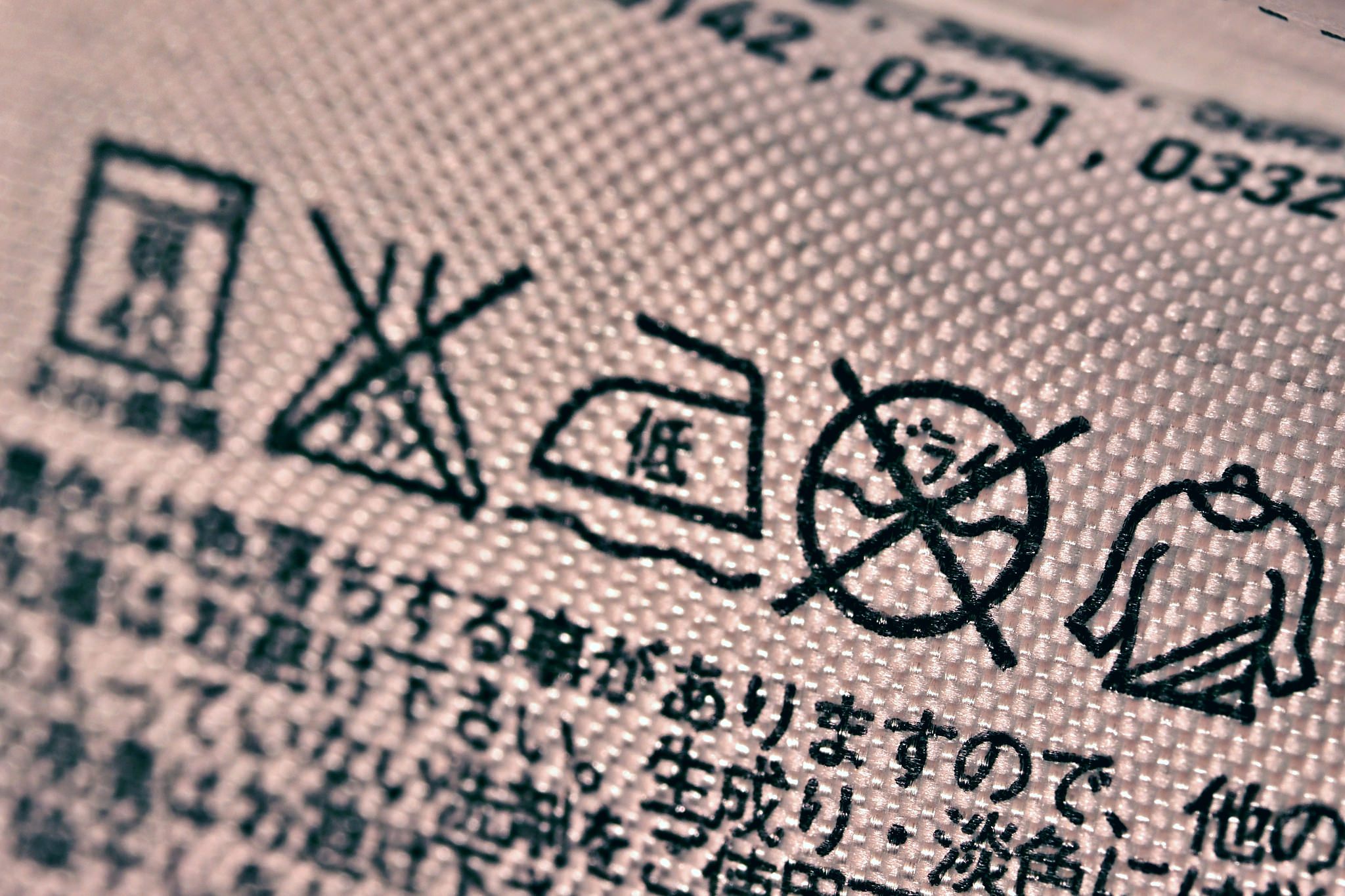

Icons for clothing care on a label. (Photo: aotaro/CC BY 2.0)

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Recently, there was a tag on an item on my clothing that was so uncomfortable that there was nothing I wanted to do more than pull it off—to send that miserable tag to a recycling bin where it would never again see the light of day.

But that annoying tag got me to thinking: Where did clothing tags come from, and who decided that an annoying tag was an important thing to have on a piece of clothing? What laws are there that lead to these tags being everywhere, and what value do they serve?

As it turns out, tags have a tangled history, from their roots as a way for labor unions to show advertise their reach to what they are today: a highly-regulated, booming industry, responsible for care instructions and, yes, that slight itch on the back of your neck. Herein: a brief history.

If you pick up a standard piece of clothing from J.C. Penney—say, a pair of Levi’s, or a plaid shirt, you’re likely to notice a few things about it. Generally, the wearable will have a handful of tags hidden somewhere, including one that prominently features the logo of the company.

But before we became obsessed with brands, labels generally had another source: It was a way for labor unions to show their strength.

At the turn of the 20th century, union labels were used by a variety of labor groups, both inside and outside of the garment industry. In fact, the first example of such labels came from cigar-makers in 1874, who used it as a way to highlight the higher product quality compared with products made elsewhere.

Clothing tag reading “union made”. (Photo: Kheel Center/CC BY 2.0)

But the most famous use of this tactic came from clothing-makers, particularly the International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), which used the tags almost as a branding strategy for the union. In fact, the union became noted in the ’70s and early ’80s for its television commercials, in which members of the union sing a ditty called “Look for the Union Label.”

The campaign came at a not-so-great time for labor unions focused on clothing. In 1976, clothing items produced by unions fell in sales by more than 500 million items, according to Cornell University. That same year, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, a union for makers of mostly men’s clothing and another major union label advocate, folded into another group, starting a long-running phenomenon of mergers in the domestic garment union space, one that eventually sucked ILGWU into the mix as well.

Nowadays, as we can barely even be convinced to wear “Made in the USA” clothing, let alone union-branded clothes, the union labels have taken on a different role: They’ve become tells for vintage clothing enthusiasts to figure out exactly when a jacket or shirt was manufactured, give or take a few years.

Unions are only part of the story, however: You can thank the Federal Trade Commission for the most important tags on your clothing—the ones that tell you how to care for a certain type of fabric.

And they had a good reason to get involved, too. For years, just a handful of basic materials were used to make dresses, shirts, pants, and similar kinds of fabrics. But as the industry evolved to more synthetic materials—think nylon, rayon, and polyester—it became increasingly unclear exactly how to care for each type of clothing. This especially became problematic when clothing started being made of different kinds of blended fabrics.

Federal law slowly started to regulate how clothing items were designated, first with the Wool Products Labeling Act of 1939, which required labels to designate whether a product is made of certain kinds of wool. A 1951 label, targeted at fur, further helped encourage the use of labeling on different products.

These two laws helped to jumpstart efforts to attach individual brands of clothing to identifying numbers, numbers that come in handy nowadays as a way to track vintage clothing sold on sites like eBay.

It makes sense that regulations would play a key role in the tagging of clothes. For decades prior, mattresses and similarly padded devices were required to include these labels for the public to be aware of what’s inside of them.

“Law labels,” as those in the mattress industry call them, were a series of state-level regulations put in place around the turn of the 20th century to ensure that mattress manufacturers weren’t hiding what was inside of a mattress—say, if you were getting horsehair instead of down feathers.

That’s a good thing, because it also ensured you weren’t bringing unwanted bacteria into the house with your new purchase. Most, but not all states, have such laws, and they extend pretty much to any kind of furniture that you’re likely to sit or lay on. The labels have long been confusing, because a key part of the regulation, the fact that consumers were allowed to take the labels off themselves, was not included on the labels for decades.

One of the best jokes in Pee Wee’s Big Adventure made fun of this oversight.

Tags on vintage clothing. (Photo: Hans Gerhard Meier/CC BY 2.0)

“Well, I lost my temper, and I took a knife and I, uh … do you know those ‘do not remove under the penalty of law’ labels they put on mattresses? … Well, I cut one of them off!” the on-the-lam character Mickey exclaimed.

(That omission meant that Pee Wee had a ride on his way to the Alamo.)

Going back to clothing labels, the real turning point came in 1960, when the Textile Fiber Products Identification Act was passed. This law was the first to require that clothing manufacturers list exactly what kinds of materials were included in an individual item, based on weight.

This law set the stage for modern labels, but it also created a lot of frustration among clothing manufacturers, who wanted the law repealed at first. Soon after the law was passed, clothing manufacturers offered their own voluntary standards in an effort to stave off additional regulation on the industry.

“If American Standard L-22 is observed by manufacturers and retailers alike, it can well prove to be far more valuable to the economic well-being of our nation than a thousand pieces of legislation like the Textile Fiber Products Identification Act,” noted Ephraim Freedman, who spent decades running Macy’s Bureau of Standards, in comments to the New York Times.

To consumers, the tags were initially confusing, something highlighted by an article in the Times’ magazine in September of that year that argued that the approach, meant to help consumers, did the opposite.

“It all began innocently enough when the cotton producers asked Congress to insist that certain blends of synthetics and cottons be identified as such,” columnist Kenneth Collins wrote in the paper. “This sounded sensible enough and the lawmakers went to work. But the deluge of fiber names that has lately swept over the textile world has left everyone in the field gasping.”

Ultimately, though, this confusion simply led to more regulations that ended up doing what the original law should have done in the first place: they told people how to wash their weird textiles with confusing-sounding names. Those regulations first came about in 1971, when the Federal Trade Commission released the Care Labeling Rule, creating standards for telling people how to care for the clothes that they bought. The rule, which has been around ever since and updated a few times, has since given value to those tags you find on your clothing.

(If you find yourself needing to write a label of this nature, here’s a guide describing everything you need to know. Considering these labels generally don’t top 50 words in length, the guide is surprisingly long.)

The biggest care label innovation came about in 1997, however, when the industry introduced little icons to replace the words that told you how you could care for your clothes. The FTC changed its rules to allow for the icons, and ever since, we’ve had tags that have become more informative than ever.

Despite the commonality of clothing tags and how often we see them (pretty much every day, honestly), it’s not often that we care enough about the issue to talk about it.

Instructions on a clothing tag. (Photo: Justin Taylor/CC BY 2.0)

But the fact remains that they’re big business. In 2007, the packaging-materials company Avery Dennison announced a $1.3 billion deal to acquire Paxar Corporation, which was previously the largest maker of textile labels.

The purchase, a major deal for the packaging-materials firm, reflected a surprising fact: apparel labels are an incredibly huge business, at least worth the value of a Twitter or Snapchat.

Paxar, see, was perhaps the largest manufacturer of both brand labels and clothing care labels at the time of Avery’s purchase of the company, and Avery has since taken Paxar’s helm.

The company currently manufactures the SNAP line of fabric printers, which are designed to quickly print fabric labels that can be used to print standard care labels that can be woven into clothing products.

For at least one company, though, the future might be tagless.

In 2002, for example, Hanes convinced millions of people that a tagless T-shirt, with necessary washing data printed directly on the shirt, was a major innovation.

The company spent millions of dollars on a marketing campaign—already sporting Michael freaking Jordan, by the way—to convince people that a white T-shirt without a tag in the back was the solution to all their itchy neck problems. And they had the data to back it up; when doing market research, Hanes found that the biggest frustration that its target audience had with its shirts was the tag, and the product was perfect as a vessel for testing a tag-free product, because it’s made of 100 percent cotton.

The campaign focused on a huge public relations push (unusual for a company that, y’know, sells white T-shirts), and while they used Michael Jordan to good effect, they also used an ad with a comedian willing to repeatedly scratch his neck. They even had a catchy slogan: Go Tagless.

The plan was immensely effective. A year after the campaign, sales were still up between 30 and 70 percent.

Take that, Fruit of the Loom.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook