The Rocky Road to Saving Hyderabad’s Stunning Geology

As the city expands into a global IT hub, a small but dedicated group fights to protect its ancient landscape.

On a cloudy Sunday morning in Hyderabad, a group of hikers makes their way across a sprawling university campus, first on paved roads lined with colorful bougainvillea and then through prickly shrubs. Their destination: pathar dil, or heart of stone, a natural formation of four boulders that stands as tall as a two-story building. Upon reaching it, the hikers rush to take pictures and try to squeeze through the gaps in the boulders, “slicing through the heart,” one of them jokes.

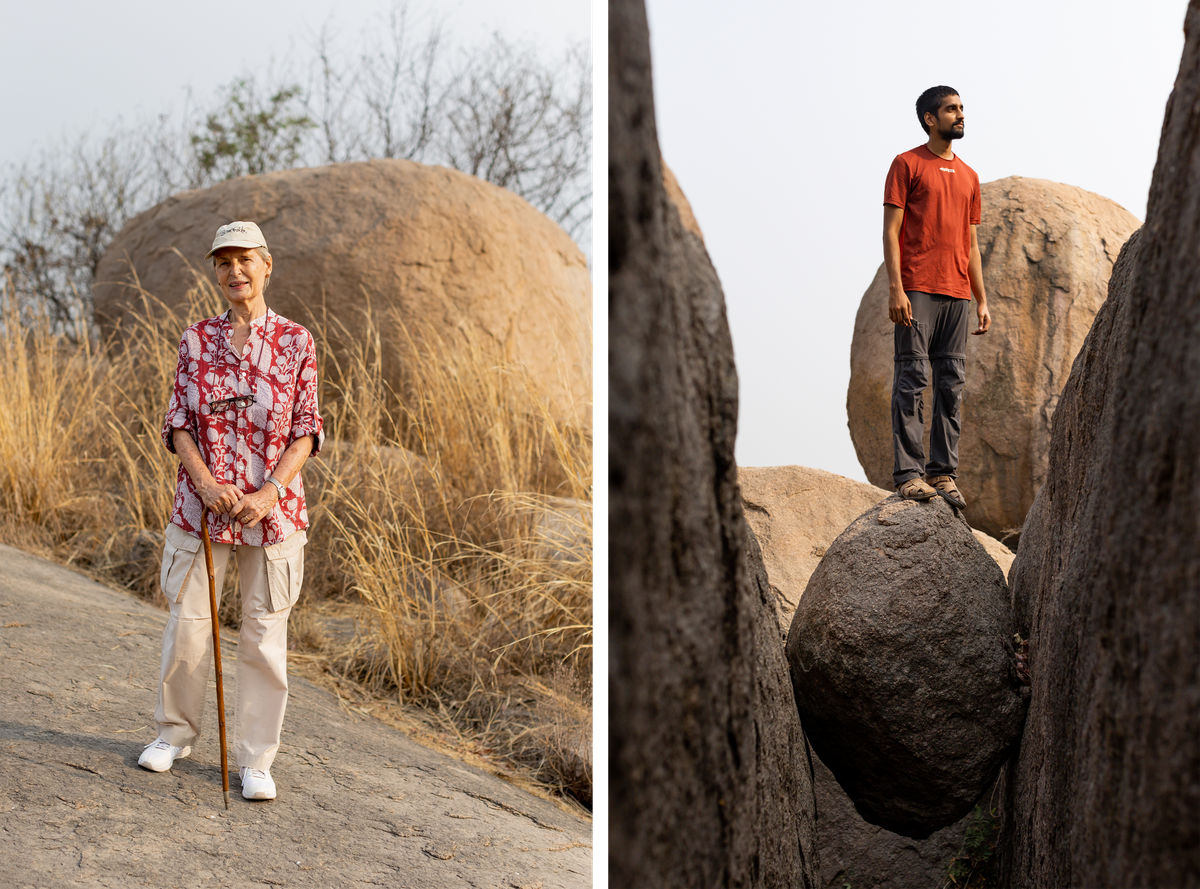

One of the oldest members on the excursion is 80-year-old Frauke Quader who has, you might say, a heart for stone. About five decades ago, the German national fell in love with a man from Hyderabad, and later with the rocks in his city.

“When you come into Hyderabad by train, there were just these unimaginably interesting rocks, huge big fields of them. It was so beautiful,” she says. Boulders of all shapes and sizes are scattered throughout the region. They’re found in unexpected places: on sidewalks, in front of luxury hotels, and even inside people’s homes. Hyderabad’s traditional art, poetry, and folk songs are full of rocky references, and the boulders play a role in the preparation of one of its most famous dishes. But now, as the city expands, the rocks are being destroyed—something Quader and a small group of like-minded activists are fighting to stop.

This south-central region includes some of the oldest rock in India; what are now the rounded boulders dotting Hyderabad and the surrounding countryside began forming deep in Earth’s crust an estimated 2.5 billion years ago. Magma from the mantle seeped upward into the crust and eventually crystallized, over millions of years, forming granite. University of Hyderabad geologist Mudlappa Jayananda says the granite in the Hyderabad region formed 3-10 miles beneath the surface and was eventually exposed through erosion. Once on the surface, the granite was sculpted by wind, rain, and changes in temperature that can cause cracking. The unusual boulders that resulted are examples of what’s known as onion peel weathering. “Continuous expansion and contraction over thousands of years leads to layer by layer of rock coming out,” says Jayananda. “That produces all the spherical-shaped [boulders],” he says.

The boulders of Hyderabad have played a part in the city since its very founding. While researching an upcoming documentary about the rocks, filmmakers Uma Magal and Mahnoor Yar Khan came across several late 17th-century paintings of Mughal figures featuring a backdrop of rocky landscapes and piled boulders; the rocks also appear in regional textile art, such as the Kalamkari tree of life motif, which depicts the many-branched tree rising out of a mound of rocks. Numerous boulders have historically served as centers of pilgrimage, or bear the inscriptions of different political and religious groups that were in power at various points in the city’s past, says historian Aloka Parasher-Sen. The rocks have even influenced local cuisine: One of Hyderabad’s famous delicacies, pathar ka gosht, is prepared by grilling pieces of seasoned goat meat over a granite slab.

Quader’s fascination with the rocks began soon after she married and settled in Hyderabad in 1975. She would look at boulders stacked precariously on top of one another as if arranged by some invisible giant and wonder, she recalls, “How is this possible? How did they get there?” As the city grew, construction and development projects started destroying the rocks—and Quader found her calling. In 1996, together with a few other rock enthusiasts, she formed the Society to Save Rocks. The group sought to raise awareness about the city’s geological heritage through photography exhibitions, concerts, and monthly walks through the unique landscape.

Their work has become only more urgent over time. Over the past two decades, as Hyderabad emerged as a technology hub, its population has more than doubled, resulting in an urban sprawl of more than 150 square miles. The would-be rock saviors aren’t against development, but worry that destruction of the rocks also means a loss of green areas and natural ecosystems.

“We love the good roads as much as anyone else. We want people to have housing. But it can’t be at the expense of lung space or ecology,” says Magal, who’s also a member of the society. Group members point to examples where developers successfully integrated the boulders into their plans. One luxury hotel incorporated a formation called bear’s nose into its grounds; a few miles away, another cluster of boulders in the shape of a tortoise sits protected in the center of a roundabout.

In the past, some of the more famous rock formations were included in municipal “heritage precincts” that offered some local protection. In 2017, however, a statewide heritage law superseded municipal decrees. The newer law protects several of the city’s forts, shrines, and colonial-era buildings, but none of the rock formations. Without any protection, we could lose the rocks forever, says Quader.

One example is Khajaguda Hills, popular among rock climbers and home to stunning caves and religious shrines. Ritvik Reddy, 28, has been exploring the area since he was a child. For him, climbing the boulders is like meditation. But over the years, Reddy says, several boulders have been leveled to create a path to the top of the hill. Last year, rocks were also destroyed when city workers began building a road (the project was stopped after activists raised objections). Then in January, Reddy says, climbers were shocked to find mounds of construction debris dumped on the hill.

“We are very connected to the rocks. We name each and every rock that we climb,” says Reddy. “When you see [the destruction] happening right in front of your eyes, it hurts.”

Destroying the rocks also wipes out the flora and fauna that call them home. “Rocks give our landscape an ability to support much more biodiversity,” says amateur naturalist Kobita Dass Kolli, who has observed insectivorous plants, the Malabar rock toad, fan-throated lizards, and other organisms that are part of the boulder-based ecosystems. Some of these plants and animals can be observed on the society’s regular walks, which have become popular over the past 25 years, but Quader says there is much work left to do to save the boulders she and her group have come to love.

“The awareness is still not enough. People take nature for granted,” Quader says. But she’s determined not to give up. “When you see even a little chance that something can be done, you try.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook