In the 1800s, Sick People Would Consult Cookbooks Before Doctors

Need to bake a pie AND cure consumption?

In most middle-class British households in the 18th and 19th centuries, you would find a booklet filled with recipes collected and curated over generations. But these guides were more than the cookbooks or housekeeping guides you’d find in today’s bookstores. Tucked between recipes for roast goose and apple dumplings were instructions for making medical remedies—everyday ingredients whipped into salves for bruises and syrups for coughs.

“People mostly, especially people of modest means, didn’t go to the doctor if they could help it,” says Arlene Shaner, historical collections librarian at the New York Academy of Medicine. “These are kind of home family guides with directions of how to take care of common ailments.”

Over the years, these all-purpose guides, which were published throughout Europe and in the United States, went through different iterations and included more recipe and how-to categories. Alongside stews and pies, the books also describe how to carve, pickle, make ink, brew beer, manage bees, and heal sprains. The treasured volumes, passed from generation to generation, give a window into the concerns, common illnesses, activities, and interests of middle-class modern homes.

“Sometimes they were called a cabinet or a Queen’s closet,” says Shaner. “It’s this idea that this is a little bit of a secret, a trade secret that someone shares with you that you wouldn’t be able to get from another place.”

Gathering medical information in short, concise recipes has a long tradition stretching from the ancient period to the late 19th century, writes Elaine Leong a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. “Historians of medicine see the early modern home as one of the main sites for medical intervention and health promotion. Householders were not only quick to combine self-diagnosis and self-treatment with commercially available medical care but many also produced their own homemade medicines.”

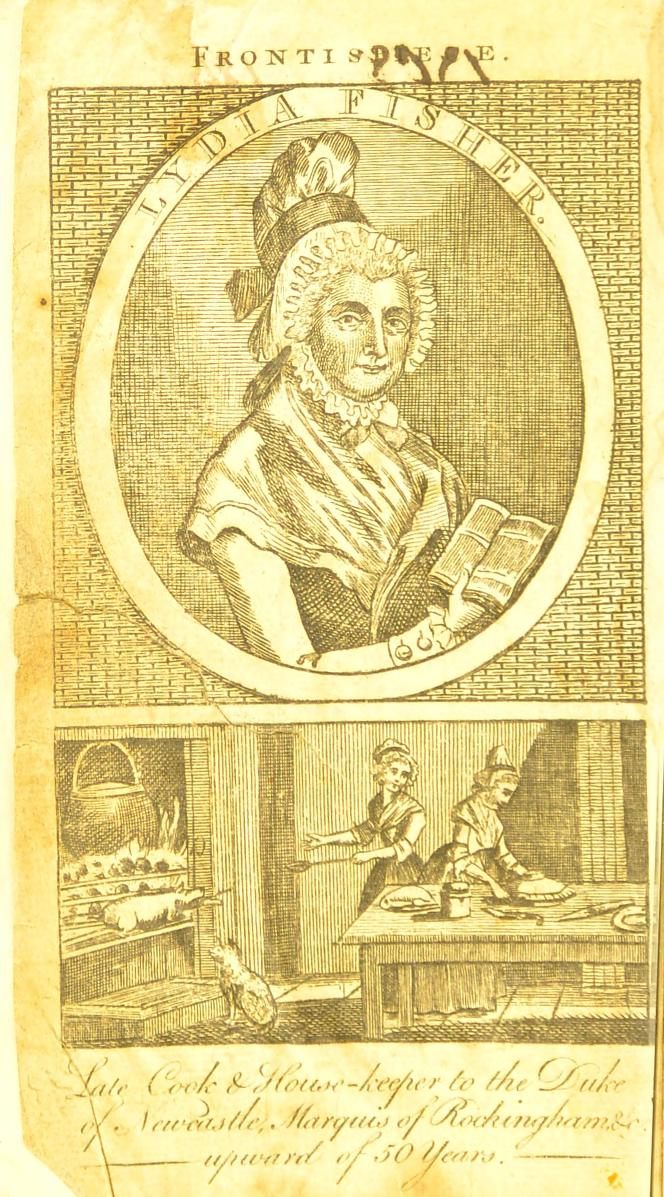

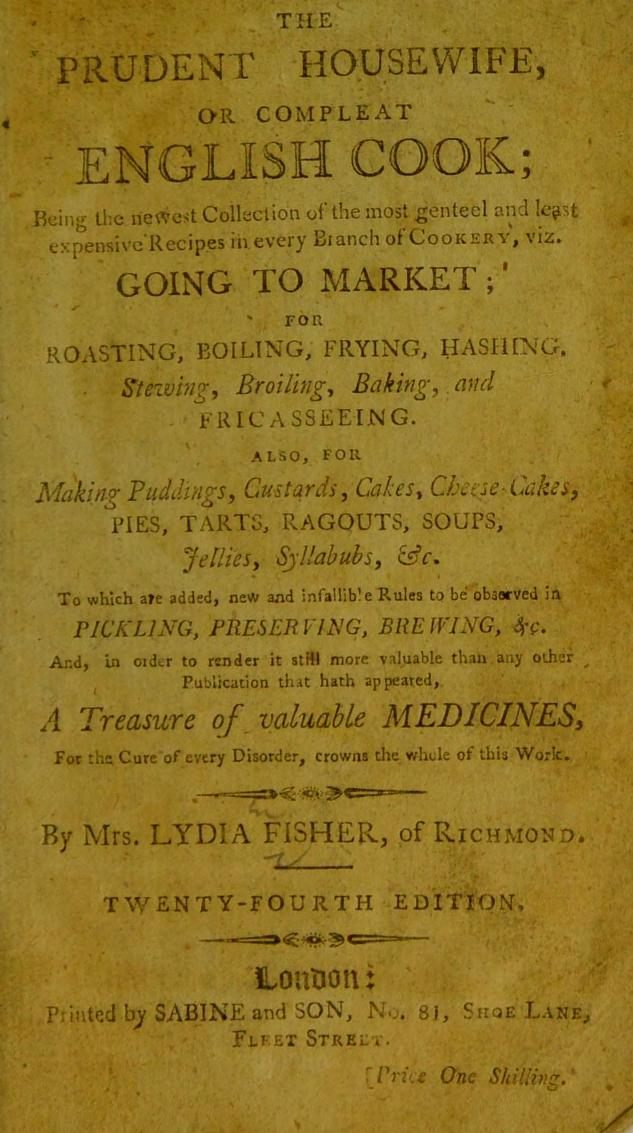

Catered more towards people of modest means, these books were written mainly by women, but there were some popular cookbooks also penned by men. One popular English cookbook, The Prudent Housewife, or Compleat English Cook, by Lydia Fisher in 1800 had at least 24 editions.

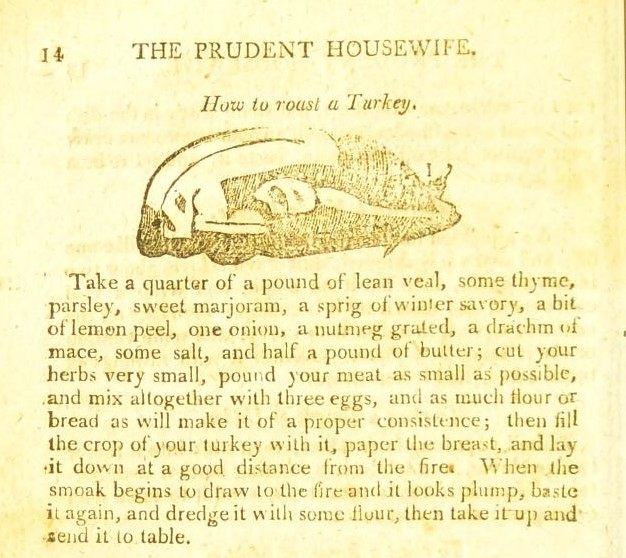

Reading through The Prudent Housewife, some medical treatments sound whimsical while others appear dangerous. For a sprain, The Prudent Housewife advises a soak in warm vinegar, and then applying a paste of stale beer grounds, oatmeal, and hog’s lard every day until the pain and swelling go away. Hiccups call for a tasty sounding syrup of liquid cinnamon on a lump of sugar, while heart burn requires a glass of water or chamomile tea with scraped chalk. To rid of giddiness, people would drink 20 drops of castor oil mixed in water, and “the smoke of tobacco blown into the ear is an excellent remedy” for an ear ache.

While it’s clear today that some of the ingredients listed in the medical recipes would not be safe to ingest, people at the time used the items and knowledge they had access to, Shaner explains.

“There are some of these remedies that you read that are distressing a little bit,” says Shaner. “If you find a recipe for a cough remedy that has syrup of poppies in it, you can guess whether or not it’s going to work.”

In the appendix of some of the books, like The Prudent Housewife, there are a list of standard base ingredients that all households should have. These would be added into different remedies, such as opodeldoc, a popular lotion or soap that was used to relieve rheumatic and arthritic pain.

Families often chose one notebook to record and annotate recipes, and add other bits of practical knowledge, writes Leong. On some of the cookbooks, autobiographical notes, confessions, and spiritual meditations are scribbled in the margins or inscribed in the blank pages left at the end of some of the books. Recipes were shared within circles of friends and books were kept within families. In some cases, writes Leong, they “were considered worthy enough to be mentioned in wills and bequests alongside other household objects of value.”

These antique cookbooks were cherished items that also serve as useful pieces of history. Some scholars even consider it the first genre of women’s medical writing, and a mark of a shift away from male dominance within the household, Leong explains.

Today, large comprehensive housekeeping guides exist, but few if any also contain medical remedies. The all-in-one books of yore are still of value, but more for their historical intrigue than their medical utility. Leeches behind the ears will not, in all likelihood, cure your headache.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook