Inside the Spark-Filled Home of a Vintage Electric Machine Collector

You get the lights, I’ll flip the switch for the Victorian teleport.

Some of Tim Mullen’s many curious items. (All photos: Ella Morton)

In his one-bedroom apartment four floors above a Manhattan Chipotle, Tim Mullen is trying to get his television to work. It takes a while, but the TV’s pretty old—almost 70 years old, in fact. It stands in a corner, all 295 pounds of it, beside a brain in a bell jar, a wart-zapping X-ray wand, and an electrostatic generator that, if you were to put your finger in the path of its spark, could easily kill you.

An RCA Victor television from 1947 stands sentinel in a corner.

Mullen is a collector of old, weird, cool-looking machines. His apartment is crammed with, in his words, “early technology, mostly electrical, from the beginning of the electric period—about 1880—right up to World War II.”

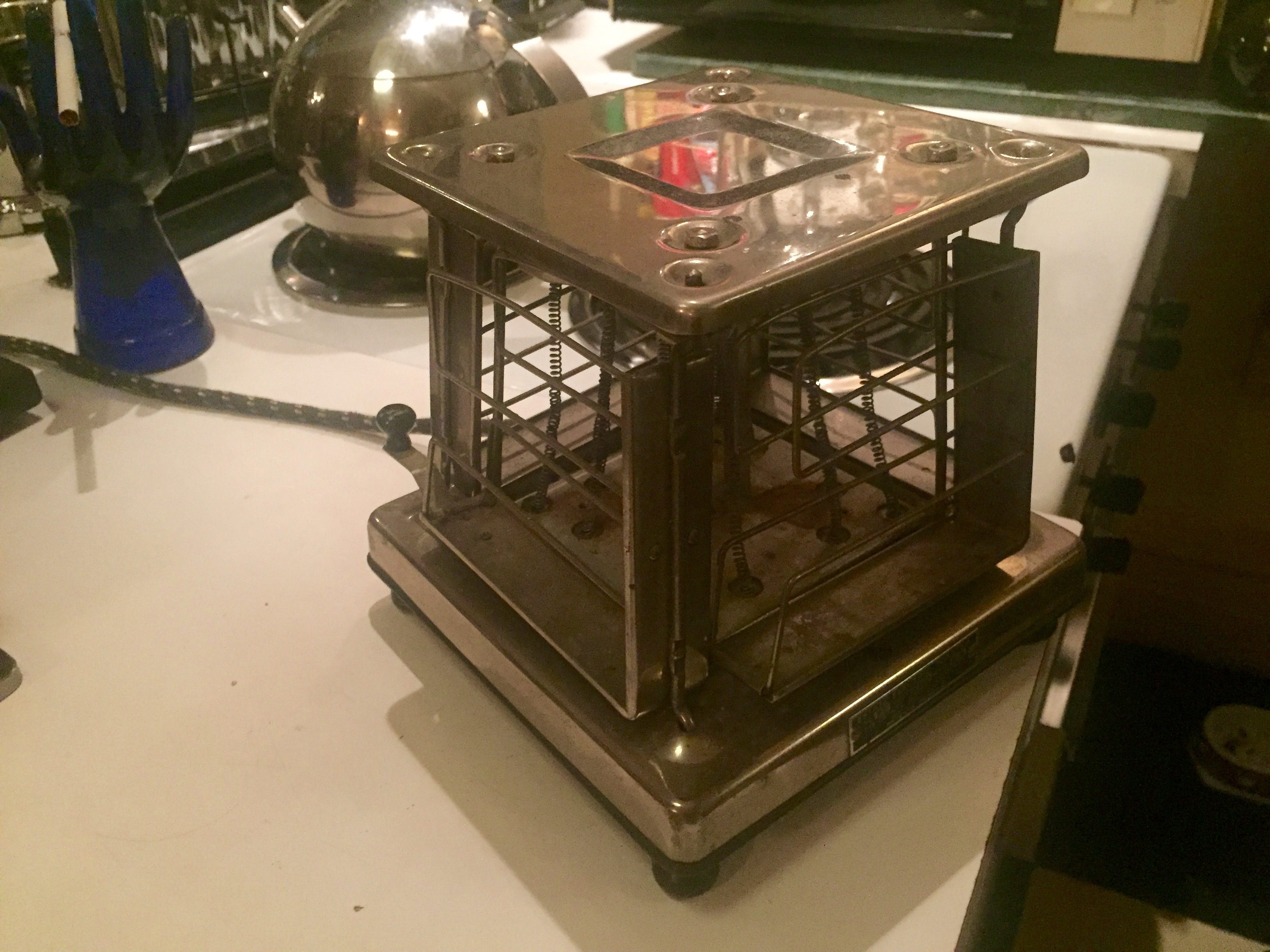

And these items aren’t look-but-don’t-touch museum pieces. Mullen uses many of them on a day-to-day basis. He’ll put bread in the ornate 1920s toaster, stream music from one of the Art Deco radios, and stand in the formidable wind of a squeaky ceiling fan that doesn’t have a safety grille.

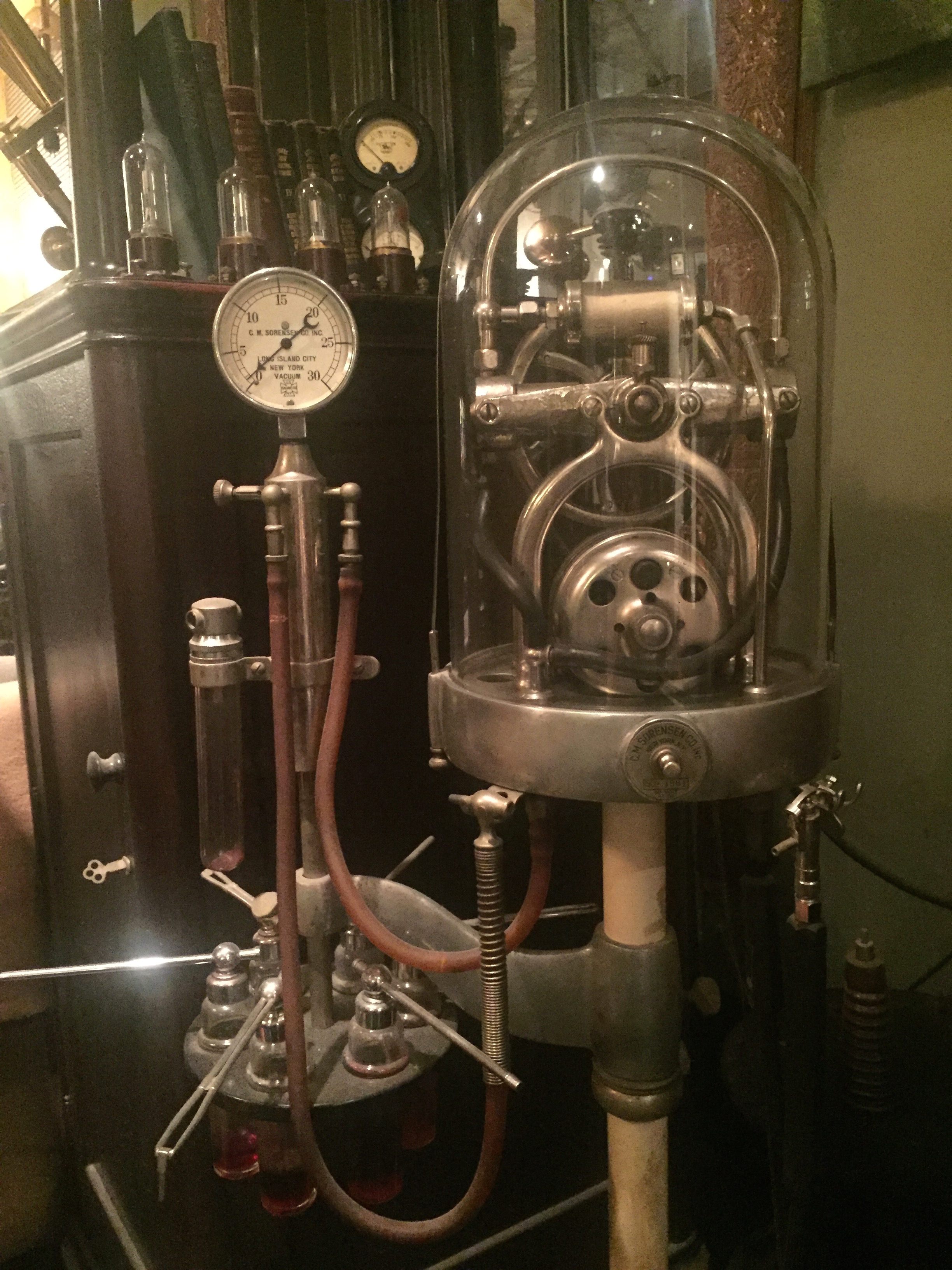

Have you ever seen a more elegant spit-sucker? Saliva-vacuuming machines like this one were used by discerning dentists during the 1930s.

Collecting—and tinkering with—vintage machinery has been a lifelong pursuit for Mullen, who, to his parents’ alarm, spent his youth building Van de Graaff generators in the basement of the family home. Now a post-production engineer with a long history of building circuits for fun and profit, Mullen delights in hunting down dusty, non-working devices and fiddling with them until they run again.

Rotating Geissler tubes were the turn-of-the-century version of disco party lights.

“It’s imperative for me, of all people—I’ve got to get that damn thing working,” he says of his beloved machines. They “give off heat, they give off light and sound, it’s almost like a critter. I want to see them be happy and work.”

Though he collects everything from pre-World War II televisions—“rarer than Stradivarius violins”—to Jazz Age dental equipment, Mullen has a particular penchant for late-Victorian electro-medical devices.

A “globe top” refrigerator from the 1930s.

Right now, his Holy Grail is the Hogan high-frequency apparatus, an electrotherapeutic machine that consists of a four-foot-tall wooden cabinet equipped with a switchboard and topped with a Tesla coil. “Here’s the punchline,” says Mullen, excitedly: “two-foot-long lightning bolts.”

These bolts would blaze and spark from the coil, accompanied by an almighty buzz. ”It’s so wild-looking it was used as a prop in the first Frankenstein movie,” says Mullen. “I really need a Hogan. They’re around. I’ve just got to find one.”

A toaster from the 1920s.

One rare and highly prized item that he has managed to get his hands on is what he calls his “Victorian teleport,” an upright glass cylinder with a wooden frame that’s perfectly sized to fit a standing human being. Above the cylinder hangs a lamp that emits an incredibly bright, white light. It is only after staring at it for a few seconds that Mullen warns not to look too long, because it tends to make one’s eyes feel “crunchy.”

The teleport lamp.

When Mullen flips a big switch on the wall, the cable suspending the lamp extends, sending the light down into the cylinder. It’s all very dramatic until there’s a bang from another room and everything goes dead. One of the circuit breakers has tripped. That happens a lot in this apartment.

Mullen built this panel to control the teleport.

The “Victorian teleport” is actually a carbon arc blueprinting frame from 1905—“essentially the world’s oldest running photocopier,” says Mullen. He got it from an antique seller in Philadelphia. To bring it home to New York, he carefully wrapped and padded the two arcs of glass, stacked them in the back of a truck, and drove 20 miles per hour “like a grandma.” When cars honked at him on the FDR, one of Manhattan’s traffic-prone parkways, he yelled, “Go around me!”

Having amassed an apartment’s worth of vintage wonders over the decades, Mullen can now approach flea markets and antique sales in a more relaxed state of mind. He doesn’t have to have everything—but those rarer-than-Stradivarius items still catch his eye.

One of Mullen’s many vintage fans. Unlike some of the others, this one has a safety grille.

Hunting around for examples of what he dreams of acquiring, Mullen pulls out a black-and-white photograph of a hospital “electric room” filled with sinister-looking furnishings, including a wicker dentist-style chair, a tube resembling a cannon, and a glass-and-wood cabinet containing a whirring turbine and X-ray apparatus.

The photo was sent to him by a friend. (“He said he’s an archivist; maybe he’s a patient at the New Jersey State Insane Asylum.”) Pointing to a mysterious machine in the photo, Mullen lights up. “I don’t know what that is,” he says. “But I want one.”

Tim Mullen will be giving a tour of his astounding collection during Obscura Day on April 16. Visit the event page to sign up.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook