How Curry Became a Japanese Naval Tradition

Ships and submarines have their own unique recipes.

An army marches on its stomach—or so goes a common saying. Something similar could be said for sailors, and for more than a century, Japanese naval forces have been kept afloat with curry.

Nevertheless, karē, or curry, is a relative newcomer to Japanese shores. The word “curry” originated in India, although it did not have a long history there. Instead, it derived from a Portuguese mispronunciation of a term meaning “spices,” which British colonizers applied to a wide swath of Indian dishes. It became a catch-all, writes historian Dr. Lizzie Collingham: “a generic term for any spicy dish with a thick sauce or gravy.” British traders and travelers wanted an easy way to recreate Indian-style dishes, resulting in the popularity of mulligatawny and country captain, as well as a booming industry in pre-made, all-purpose curry powder.

This was the curry powder that 19th-century British sailors took with them to Japan. The timing was serendipitous. The Meiji era, starting in 1868, was a time of both increasing foreign influence and domestic militarization. The Japanese government needed to feed its soldiers and sailors healthily and in bulk. One major issue was beriberi, a vitamin deficiency that killed Japanese royals and commoners alike. Beriberi stems from a lack of thiamine, an essential nutrient, and eating polished, thiamine-free white rice was a sign of refinement and wealth. The Imperial Navy and Army offered unlimited white rice to attract recruits, and many ate little else. The deficiency soon became a drastic problem, laying low thousands of soldiers during the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War.

While the true cause of beriberi stayed mysterious for decades, navy officials pinpointed diet as the cause. To save their sailors, they examined the food provided in other navies, particularly Britain’s. Many British ships served curry at the turn of the century, though it was leagues away from Indian curry. Instead, the British version was a mix of tinned curry powder, butter, meat (typically beef), root vegetables, and a sauce thickened with flour. Since both meat and flour contain thiamine, curry was practically a silver bullet against beriberi. Served over a heaping portion of rice, it could also feed an entire mess hall.

Soon, Anglo-Indian curry became a standard meal in the Japanese navy. (Navy officials were more inclined to accept dietary innovation than the army, which suffered beriberi long into the 20th century.) Civilians couldn’t resist either. According to Japanese food writer Makiko Itoh, the first Japanese recipe for curry was published in 1872, and restaurants began serving it in 1877. In 1908, the official navy cookbook, the Navy Cooking Reference Book, was issued with a recipe for curry made with meat, flour, and butter. Even the army got into the curry game eventually: According to Collingham, the army advertised that recruits could expect meals of glamorous curry.

After World War II, former servicemen returned home with a taste for curry. By then, variations abounded in Japan. The only commonality was the sweet, gravy-like sauce, which is draped over fried pork cutlets, omelets, or rice, or served with noodles or even secreted inside savory donuts. Heat levels range from none at all to fiery-hot. By the 1950s, curry sauce could be easily made at home from prepackaged roux cubes. Popular brands, such as Vermont Curry, are flavored with honey and apples.

While Japan dissolved its military after World War II, the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force, established later in 1954, continued the naval curry tradition. JMSDF ships serve curry every Friday, supposedly to help sailors mark the passage of time. According to Itoh, “each JMSDF ship prides itself on having its own unique curry recipe.” Different ship’s recipes can contrast starkly due to unusual ingredients—the curry served on the Hachijo patrol ship, for example, includes ketchup, coffee, and two kinds of cheese.

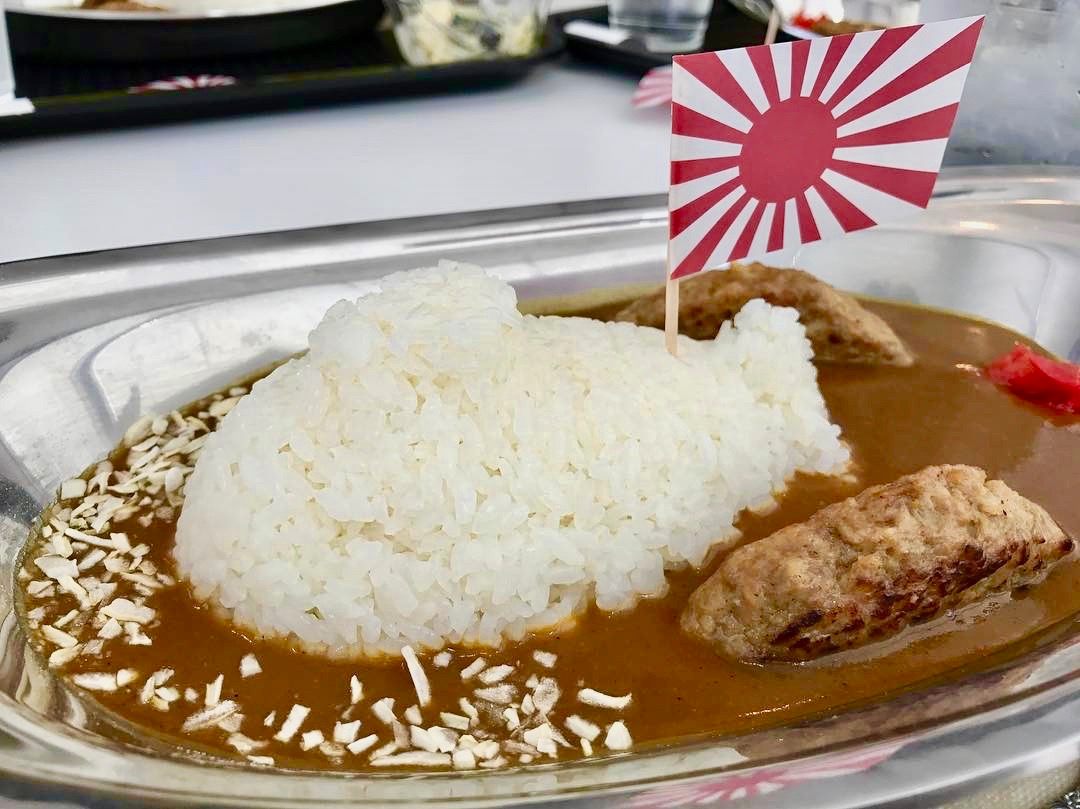

To the delight of military buffs and curry fans, some vessels have granted select restaurants permission to reproduce them on shore. At these establishments, cooks dish up navy curry with mess-hall flair in gleaming metal dishes. They may mold the rice into the shape of a ship or submarine, surrounded by a lake of curry, and the finishing touch is a little paper flag with the emblem of the rising sun (the official symbol of the JMSDF).

The navy curry scene centers around two traditionally seafaring Japanese cities. The appropriately-named city of Kure boasts many options for “Marine Self-Defense Force Curry.” Near the Kure Maritime Museum, which commemorates the famed World War II Yamato battleship, the Seaside Café Beacon serves the curry from the JS Samidare, which includes beef, pork, and chicken, served with nan. An online list points out where to try the corresponding curry of nearly two-dozen more transport vessels, minesweepers, and submarines.

In contrast, the city of Yokosuka, the home of the U.S. Yokosuka Naval Base, tends toward tradition: Many restaurants serve a version of the original Navy recipe from 1908. A typical example can be found at Yokosuka Kaigun Curry, where set meals come with the traditional navy accompaniment of a glass of milk and a salad, for maximum nutrition. Yokosuka’s official curry mascot, the Donald Duck look-alike Sucurry, is often depicted carrying a plate of curry. At this year’s Yokosuka Curry Festival, which the town holds in May, 50,000 visitors came to sample 89 different curries, in the shadow of the decommissioned Mikasa battleship.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook