How to Ensure the Last Gas-Lamp Theater in the World Doesn’t Blow Up

Though safe today, antique lights once posed risks of poisoning, suffocation, asbestos, radioactivity, and explosions.

There’s a low hiss, a spark, then a momentary brilliant blaze. The outline of red velvet seats, ornate moldings, and a sweeping balcony emerge from the shadows, all now illuminated by an apricot glow. “I think of it as waking up the building,” says Wendy Cook, Head of Cinema at the Hyde Park Picture House, as she stands in the empty auditorium, long lighter in hand.

Cook has worked at this small neighborhood cinema in Leeds, England, since she began selling sweets here 20 years ago. She estimates she’s lit the cinema’s nine gas lamps thousands of times. “It’s just part of my daily routine,” she says, “like muscle memory.”

Yet Cook’s everyday ritual is wholly extraordinary; this Edwardian picture house, which has been operating since shortly before World War I, is thought to be the only gas-lit cinema in the world.

The building reopened in June 2023, following a three-year renovation that cost £4.8-million ($6-million) in order to improve capacity, accessibility, health, and safety. “As soon as the project reached public consultation, everybody’s first question was, ‘Are you retaining the lamps?’” says project architect Mark Johnston.

Although converting the lights to electricity would have saved a lot of work, Johnston explains that option was a complete non-starter. “It’s the lamps that make the building unique and give the feeling that you’re being transported back in time,” he says. “I don’t think the end result would have been as significant or as well received by the public if we’d used modern LEDS.”

But to keep gas coursing through the 109-year-old building—leading to nine flickering flames—the team had to satisfy insurance companies, safety inspectors, and themselves that they had minimized the risk of fire, explosion, gas poisoning, and suffocation. The task was made all the more challenging, because they needed to learn the secrets of an almost-extinct trade.

“Not many people have experience in gas lighting,” says Lawrence Williamson, the senior mechanical engineer on the project. “And there’s nothing relating to gas lighting in the regulations.” With no building plans for guidance, they stripped back the plaster to discover “a spiderweb of gas pipes everywhere.” The spaghetti system led back to a single copper pipe in the basement, with one on/off hand-operated isolation valve, which was always left open.

The only other way to control the gas flowing into the foyer and auditorium was a publicly accessible valve on each lamp. “If somebody came along and blew the lamp out, it would still be bleeding gas in the middle of a showing,” says Williamson. Due to the size of the auditorium, the ventilation system, and the small amount of gas involved, Williamson says a lamp could be left running for a day with minimal risk and no detection. “But, if a lamp was left bleeding gas for an extended period, it could pose a serious fire risk for the building,” he adds.

To assert some control over the knotty operation, the design team decided to strip everything and start again. Copper pipes—with their fickle joints and potential to let gas seep, unnoticed, into nooks and crannies—were changed for continuous plastic-coated pipes. Each lamp was given its own clearly numbered feed and isolation valve in the basement, plus an additional valve was placed in a tamper-proof box embedded in the wall below each lamp. The team then installed a new alarm panel and a hidden network of sensors, meaning the slightest whiff of smoke or carbon monoxide would now automatically shut off the gas rather than requiring a staff member to scurry down to the basement.

Yet, another conundrum remained: How to calculate how much gas should flow through each lamp? Williamson says he spoke to several different gas companies: “They told us: ‘We don’t know, and there are no regulations for gas lamps, because they’re that old.’” Eventually, he heard back from heritage lighting specialist Chris Sugg. “When I showed him pictures of the lamps,” says Williamson, “He said, ‘I made those.’”

Sugg explains he crafted the fixtures for the Hyde Park Picture House in 2004, when the theater had decided to replace their then-elderly lamps. Although he’d recently sold his business and retired, he used leftover brass tubes and components to solder together nine swan-neck lamps in his shed. “They’re completely handmade,” he says.

“We then had the interesting problem of how you keep a gas light dark,” says Sugg. Gas companies had often marketed their lamps as producing the nearest light to sunlight. Eight of these lamps, though, needed to provide more subdued, cozy lighting during screenings. The solution came in the form of glass surrounding the flame. “I spoke to our glass supplier, and he came up with this Marmite color, which produced a dark brown glow,” says Sugg. The murky glass in the bell-shaped lampshade ensured the light mainly shone downwards rather than dazzling the audience.

Sugg replied to Williamson about the gas flow and how best to control and care for the lamps. “The biggest problem with gas lighting has always been one of keeping fixtures clean,” says Sugg. He explains that the small air holes in the lamps need to be kept clear to allow oxygen to mix with the gas to support proper combustion.“Problems can be caused by spiders that climb into little holes.”

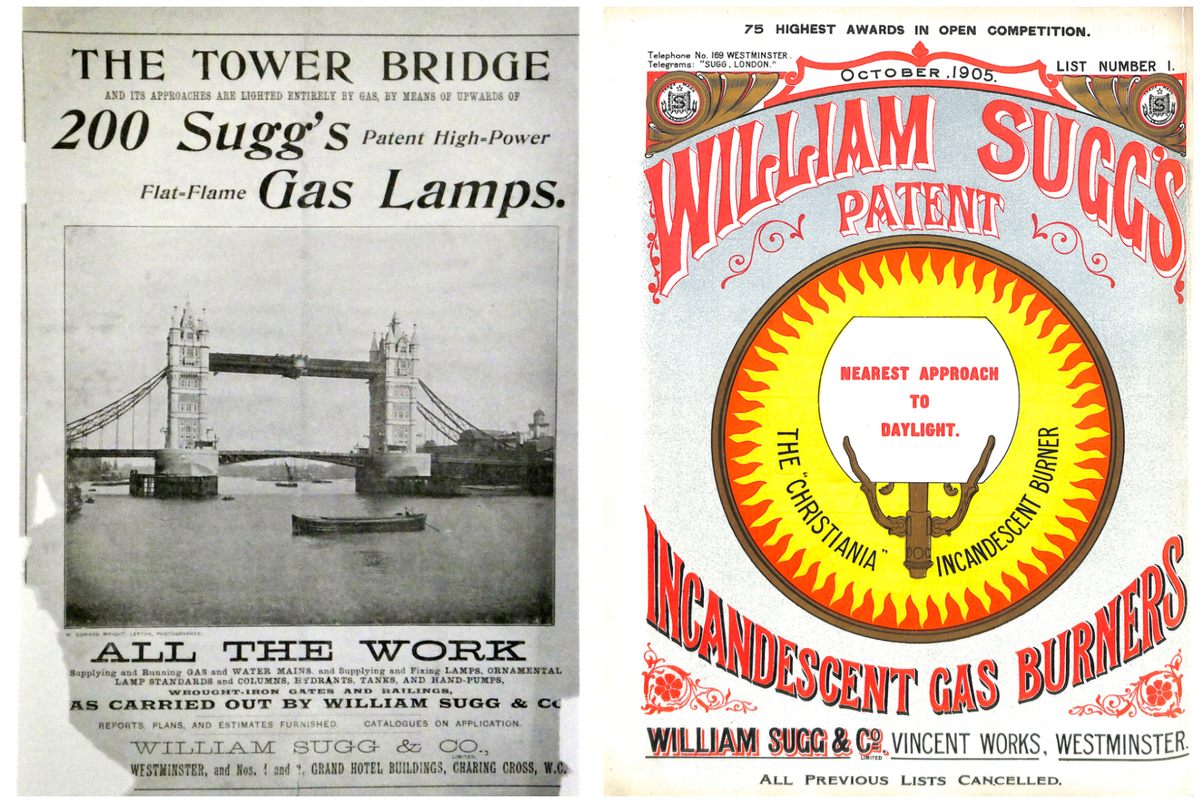

Sugg’s knowledge of gas lighting runs deep. His great-great-great-grandfather, Thomas Sugg, made the gas pipes for the first recorded public street lighting in Pall Mall, London, in 1807. His great-great-grandfather William then established the pioneering company William Sugg & Co in 1837, which went on to install gas lights everywhere from domestic drawing rooms and train carriages to the Houses of Parliament and Buckingham Palace.

Although the current focus on the lamps revolves around their risks, gas lighting started as a trailblazer of health and safety. “If it was a cloudy evening, cities were dangerous places,” says Sugg. Before street lighting, people hired torchbearers to escort them to their destination and provide protection against pratfalls and attacks. But there were accounts of untrustworthy torchbearers leading their unsuspecting wards into the clutches of robbers. What’s more, theaters were primarily lit by candles, which not only sometimes caused fires, but the gloomy lighting also made the settings notorious for theft and indecency. Installing gas-powered modesty lights, such as those at the picture house, provided a small step forward in protecting women, in particular, from groping, malevolent hands.

And so gas lamps became preferable—but they could still cause a fair share of problems. “The beginnings of gas lighting came with open flames,” says Sugg, who likens early lamps to bunsen burners, posing an inevitable fire risk.

In 1826, for example, an East End London theater and gasworks burned to the ground when some gas stage lights set fire to the scenery. Gas fixtures also ran off town gas, which was produced by heating coal and was highly poisonous. All the same, the clamor for brighter illumination meant gas lamps started getting larger, more elaborate, and fuel-greedy—some reaching the size of a grown man. “The lamps had to be that big, otherwise they would simply melt, because the amount of heat coming from these huge flames was enormous,” says Sugg.

A breakthrough came in 1884 when Austrian chemist Carl Auer von Welsbach invented the incandescent mantle, a fragile tubular flame cover that helped provide a bright light with a fraction of the fuel and heat. By the early 20th century, as the Hyde Park Picture House opened its doors, more robust inverted mantles were available, allowing flames to shine downwards. Although, as Sugg points out, the early mantles themselves had associated risks, since they contained both asbestos and radioactive substances for a heightened glow.

The mantles used by Cook and her team in Leeds no longer contain materials we now know to be dangerous. Although, as gas lamps fall further out of fashion, the mantles have become harder to source. But Cook feels sure they’ll find a solution. “There’s always innovation, even in relation to heritage,” she says. “So I think that whilst there will be issues with mantles at some point, I won’t be surprised if something can be made.” However, as the UK looks to move away from mains-supplied natural gas to more renewable power sources, Cook is clear-sighted about the need for the picture house to adapt—just as it did with the arrival of the talkies and the multiplex—so it can be in a position to celebrate its next centenary.

For now, though, this Grade II listed cinema sits among redbrick terraces, at the heart of this small, diverse community, enjoying its time in the spotlight. “People have really responded to the idea that this is the last gas-lit cinema,” says Cook. “And I think they get a real kick at finding such a precious piece of heritage here in Hyde Park in Yorkshire.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook