The Aftermath of a Fire at the Museum of Chinese in America’s Archives

Staff are hopeful after the first recovery effort found 150 boxes in a salvageable state.

On the evening of January 23, Yue Ma, the director of collections at the Museum of Chinese in America, was on her way home from work when she got a phone call from a colleague. A fire had broken out at 70 Mulberry Street, the home of the museum’s archives, where Ma has kept careful watch for 13 years. As soon as Ma stepped off the train, she got in her car and drove straight to back to Chinatown in Lower Manhattan. When she arrived, around midnight, flames were coming out of the windows on the fourth floor of the building. “I was so shocked,” she says. “We thought our collection could be destroyed.”

The fire burned throughout the night and into the next day, battering the historic building, which also houses the Chen Dance Center, a senior center, and other community groups, according to The New York Times. Nine firefighters and one civilian suffered minor injuries. Museum officials, after learning they might not have access to the building for three weeks, feared their collection of 85,000 objects might be destroyed, not from the fire but the water used to extinguish it. But on January 29, that city workers began recovering boxes that appear to be salvageable, Gothamist reported. 150 boxes—fewer than earlier estimates—were recovered on the first day of retrieval, Ma says. It’s a small fraction of the entire archive, the fate of which still hangs in the air as the recovery process continues and water seeps in.

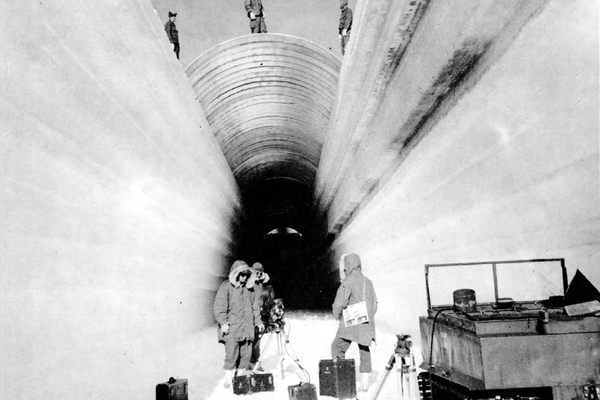

Approximately 40 of the boxes recovered showed clear signs of water damage, Ma says. They were immediately shipped to Allentown, Pennsylvania to be frozen and freeze-dried, a process that prevents future damage. These boxes were the worst-hit in part because they contained paper documentation, including books, photographs, and magazines, Ma says. The other boxes contained a potpourri of history. “We found porcelain dishes from Chinese restaurants and costumes and a stage prop from a Cantonese opera,” Ma says.

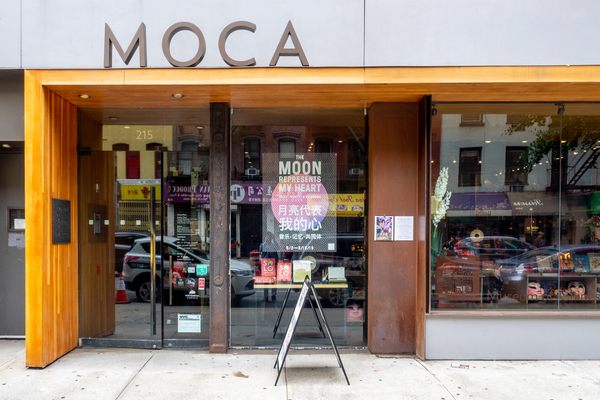

While museum officials wait for the city to announce when the next retrieval process will be, Ma keeps thinking of different objects in the collection that remain in the building. “We have a Chinese typewriter machine, which is really rare and might be one of two in America, and we have paper sculptures, which are probably damaged by water,” she says. “And we have rare books, letters, family histories, materials from businesses and grocery stores, school records, and immigration materials.” But Ma says she’s also been thinking about what has been saved, such as flight logs from Hazel Ling Yee, the first Chinese-American woman pilot, which were recently transported from the archives to go on display at the museum’s main building on 215 Centre Street.

The museum started in the 1970s as the Chinatown History Project, the brainchild of local activists Charles Lai and John Kuo Wei Tchen. The two collected trash off the street and interviewed elders at the senior center at 75 Mulberry—the beginnings of the collection that has, at least in part, escaped destruction, according to The Nation. In 2009, the expanded and official Museum of Chinese in America moved into its new home on Centre, a former machine repair shop redesigned by architect Maya Lin, but the archives remained on Mulberry. Earlier this year, the museum was criticized for potentially receiving community investments as a part of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plan to build a new jail in Chinatown, which activists saw as a sign the museum was contributing to displacement and gentrification in Chinatown.

Though the fire’s effects may still be devastating to parts of the collection, Ma says she feels grateful for the outpouring of support she’s received from museum donors. Many called to ask if she and her staff and interns were okay, and to offer to donate more of their personal belongings to help rebuild the museum’s collections. “That made me feel so warm and supported, like my work is important to them,” she says.

On January 29, the first item to emerge from the green blockade shielding 75 Mulberry was a Chinese orchid belonging to H.T. Chen, the founder of Chen Dance Studio, which was on the second floor. Chen was amazed to see his orchid still very much green and alive. “Chinese people say that the orchid represents fertility, refinement, thoughtfulness, good luck and prosperity,” he wrote in an email. “Certainly unexpected and hopefully a sign of rebirth and better times ahead.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook