Saving the Hogs of Ossabaw Island

An eccentric heiress, a daring mission, and the fight for North America’s most unusual pig.

The three bodies were lying in a clearing when he spotted them. It was still morning on June 16, 2022, but the temperature was already hovering around 90˚F. The sun beat down through a thick canopy of sawtooth palmetto and oak branches draped in Spanish moss as John Crawford, a naturalist and marine educator at the UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant, slowed his pickup truck to a halt.

Sitting beside him in the passenger seat, Dr. Michael Sturek saw tufts of wiry black fur visible between a dark flurry of feathers. Although the corpses were still too fresh to emit much of a stench, eight vultures were already ripping the flesh from the bones. “There may have been another one in the woods too,” Sturek said. But he thought that corpse had been there longer. “As we were driving by there was a smell of decay.”

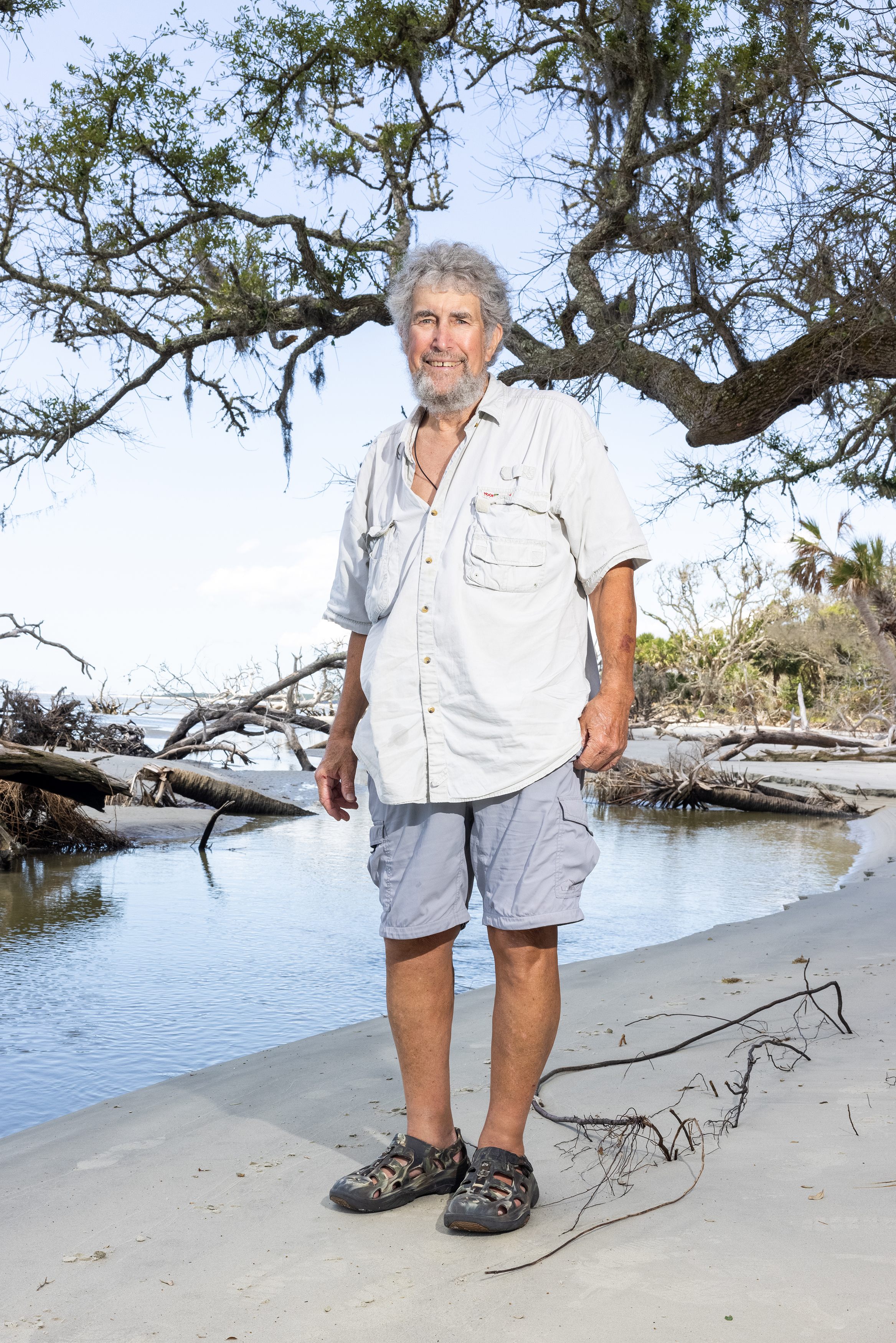

Crawford was used to the gruesome sight. With his tangle of white beard and wide, sky-colored eyes, Crawford, known as “Crawfish” to his friends, is something of a local legend. For more than 30 years, he has taken his boat out to Ossabaw Island, a human heart-shaped landmass roughly 20 minutes by boat off the coast of Georgia. There isn’t a plant or an animal on Georgia’s third-largest barrier island that he can’t identify.

That day, his passengers were Sturek and a team of researchers from the University of Indiana, who had come to see live Ossabaw hogs, but so far, had found only dead ones. Pigs cannot sweat, so living Ossabaw hogs tend to seek refuge in the murky waters of old alligator holes during the oppressive heat of the day. More importantly, these particular hogs have grown adept at running for cover at the first rumble of an engine. And with good reason: most of the humans they encounter are shooting to kill.

As far as Georgia Department of Natural Resources (DNR) officials are concerned, the hogs are an invasive species and a menace. They have an ability to rip up impressive swathes of ground with their rooting, destroying native vegetation in the process. They’re also the ultimate omnivores, eating just about anything they can find—including the eggs of the loggerhead sea turtles that nest on Ossabaw Island’s beaches.

No one has ever done a comprehensive survey of how many of these feral pigs roam the island, but estimates range from 5,000 to 10,000 on an area of around 40 square miles. In an effort to cull “the feral hog population to a level at which there is no measurable impact on the environment,” the DNR has been leading organized hunting trips twice a year. The hunts only take out a fraction of the hogs necessary to curb population growth. That’s why, for decades now, a small number of DNR employees have been slaughtering as many as 1,000 to 2,500 hogs annually. The carcasses are left to rot.

More than six million feral hogs roam throughout at least 35 states across America, but none of them are quite like the hogs of Ossabaw Island. That’s because their DNA remains virtually unchanged from when Hernando de Soto and his fellow conquistadors brought 13 pigs with them to North America in 1539. Other feral hogs interbred with their domestic counterparts. Not so with these swine, who remained isolated by their island habitat for centuries. Even as the DNR has waged war on them for decades, others have fought to save them from extinction.

As genetic refugees from the past, Ossabaw hogs are invaluable. Chefs prize their meat for charcuterie and barbecue. Medical scientists view them as a vital research tool. Preservationists at the Livestock Conservancy view them as a crucial heritage breed. Historians have deemed them the pig of choice at Colonial Williamsburg and Mount Vernon, because they represent the closest living link with the agrarian past of the early American colonies. Meanwhile, the Slow Food Foundation lists them in its Ark of Taste, a compendium of culturally significant foods in danger of disappearing.

In the spring of 2002, Sturek, along with Dr. I. Lehr Brisbin, a research scientist and professor at the University of Georgia, realized that these unique animals were in danger of vanishing altogether.

The bizarre chain of events that these co-conspirators orchestrated can only be described as a pig heist: an epic undertaking to save the Ossabaw hog involving swine smuggling, birthing piglets in a bathtub, and a rather creative interpretation of the law. It would also be the last time a genuine Ossabaw hog would make it to the mainland alive.

Centuries of Darwinian selection have given Ossabaw hogs a few evolutionary advantages over the average pig. For starters, they’re the smallest mature feral swine in the world, often clocking in at a mere 100 pounds. They can tolerate incredibly high levels of salinity, allowing them to drink the saltwater in the island’s marshes. What’s more, they have the ability to store an astonishing level of body fat that enables them to survive when their food supplies run low.

Here’s the other thing to know about Ossabaw hogs: they’re delicious.

In 2007, Jean Anderson, a member of the James Beard Cookbook Hall of Fame, wrote in Gourmet magazine that Ossabaw pork was “so luxurious, so complexly flavored, so tender it barely needed chewing.” Tom Colicchio praised Ossabaw pork because, unlike most commercially raised pigs, “It wasn’t raised to taste like nothing,” he told a reporter in 2008.

Marc Mousseau, who in 2013 founded Hamthropology, a farm in Georgia dedicated to preserving and breeding Ossabaw hogs, echoes the sentiment: “If you cook pork raised by a factory farm with no seasoning, you realize it tastes like nothing,” he says. “You’re not seasoning the meat, the meat is just a vehicle for the seasoning.”

Prior to the pandemic, Mousseau had 668 Ossabaw hogs, the largest purebred captive herd. His herd is much smaller these days, after the toll that COVID took on the restaurant industry. He hopes to regrow it, in part because he believes many more people would become converts if they could just try this exceptional pork. “When we do a barbecue, the flavor profile of an Ossabaw hog speaks for itself,” he says. “There’s nothing like them.”

Mousseau got into the business because he saw a demand that wasn’t being met. “I started talking to local chefs and they were like, ‘Hey, if you can get these animals, we’ll buy them,’” he says.

When Mousseau sold a whole Ossabaw hog to Linton Hopkins, the James Beard Award-winning chef behind Restaurant Eugene offered to cook it and sell it online for $26 a pound. “It was all prepurchased within an hour,” Mousseau says.

There’s a reason why Ossabaw hogs taste so much better. Since 1987, when America’s National Pork Board attempted to rebrand their product as “The Other White Meat,” domestic pigs have been increasingly bred for leanness. Fat equates to flavor, and robbing pork of it often leads to dry, bland cuts. Yorkshire pigs and other common domestic breeds can’t come close to the taste and texture of Ossabaw hogs, which have a higher ratio of lard per pound than any other breed of swine.

Much like their Spanish ancestors, Ossabaw hogs are partial to acorns, which fall in abundance from live oaks on the island during part of the year, as well as crabs dug up on the beaches. When acorns and crabs are plentiful, the pigs gorge, stocking up as much fat as possible for times when their food sources grow scarce.

For chefs, that fat is liquid gold. “You should not be getting rid of Ossabaw fat, you should be scraping the bottom of the jar like a peanut butter jar,” Mousseau says. His freezer is stuffed with vacuum-sealed Ossabaw lard, which he uses for everything from sautéing broccoli to making “unreal” French fries. “My daughter won’t allow me to cook fries in anything else.”

Not only are they one of the fattest terrestrial animals on Earth, but that lard is evenly distributed through their muscular little bodies, making for meat as richly marbled as Kobe steaks. The Ossabaw hogs of today closely resemble Spanish Iberian pigs. In other words, the pigs that the DNR was leaving for the buzzards are dead ringers for the same coveted swine that can fetch up to $1,400 a haunch when turned into jamón.

As an added bonus, the lard laced through an Ossabaw’s musculature is packed with omega-3 fatty acids and oleic acid. It’s not exactly olive oil—but it’s not as far off as one might think. To prove that point, Mousseau often turns to a favorite theatrical flourish when introducing an audience to Ossabaw pork.

“While I’m giving a talk, I’ll shave off a chunk off of the fat and by the time I’m done talking, that fat will have melted,” he says. That makes it considerably heart-healthier, and it also means that it liquifies sooner in the cooking process, suffusing the meat with rich, porky flavor.

According to Mousseau, it matters to have pure Ossabaw hogs in the gene pool. Although some farmers have crossed Ossabaws with Berkshires or other larger breeds, by the second or third generation, these hybrid pigs start to lose the traits that make them so special. “The Ossabaw needs to stay pure in order to continue its flavor profile, otherwise the flavors of the other pigs start to dominate,” he says. He likens it to copying an old VHS tape over and over. Without a master copy, the image grows increasingly distorted, eventually blurring into unrecognizable static.

The only route to Ossabaw Island runs through Hell’s Gate, a treacherously shallow half-mile stretch of salt water where a careless rudder can easily run aground in high tide. Most of the names attached to the island evoke death. There’s Hell Hole Road, leading to Hell Hole Pond, where enslaved workers once harvested rice in the steaming southern heat. Then there are the ghost trees, fragrant red cedars and live oaks poisoned from the inside out as salt water seeps up their roots and through their veins. Their sun-bleached limbs litter the boneyard beaches.

“Maybe it’s just a hell of a place,” Crawford says, turning to me and photographer Christopher Lane from the driver’s seat of his pickup truck. My journey to Ossabaw Island occurs in June 2022, exactly one week before Crawford will lead Sturek and his team of researchers around for their return trip.

For a place with such ominous nomenclature, Ossabaw Island is hauntingly beautiful. Much like the swine that inhabit it, the island remains defiantly untamed. Remnants of the island’s past are everywhere. During the Ice Age, giant ground sloths roamed the south of what is now Georgia, along with mastodons and woolly rhinoceroses, whose fossils have been found in the area.

Humans first settled on the island more than 5,000 years ago and the oyster shells they left behind are still visible. In 1763, John Morel, Sr. set up an indigo plantation on the island, bringing with him 30 enslaved men, women, and children. Some of their old quarters are still standing, maintained both as functional structures and a kind of memorial.

As we near an immense stucco wall with a wrought iron gate, Crawford slows the truck to a crawl. Inside is the former residence of Mrs. Eleanor “Sandy” Torrey West, the plate-glass heiress who inherited the island in 1959 and called it home for decades. For years, the only way to visit Ossabaw Island was a personal invitation from West.

In 2021, West passed away at the age of 108. From 1986 up until 2016, when Alzheimer’s forced her to move into a nursing facility, West lived full-time in the 15-bedroom, 20,000-square-foot, pastel-pink Spanish Colonial Revival mansion we are approaching.

“[West and I] were good friends for 50 years,” Crawford says. “She was just a wonderful person. She wanted to save this island. She thought the island had something to say to people, to inspire them.”

When Sandy’s wealthy parents moved from Michigan to Georgia in the 1920s, local realtors began hounding the family in an attempt to secure some of their fortune. At her wit’s end, Sandy’s mother asked her husband how she could get rid of the nuisance. “[Her husband] said, just make a ridiculously low offer and they’ll leave you alone,” Crawford says with a laugh. One place they seemed eager to unload was Ossabaw Island, a 26,000-acre-jewel with 13 miles of unspoiled beachfront. “And so she said ‘$150,000,’” Crawford continues. “And they went, ‘Sold!’”

Walking around the abandoned mansion now, it’s hard to fathom how opulent it must have been when it was built in 1924. The 12-by-14-foot plate-glass window in the front was, at the time, the largest in North America. Today, the house is slowly falling into ruin, the gardens throttled with vines. Even the statues of a pair of Ossabaw hogs have gathered moss. The Ossabaw Island Foundation hopes to raise the money to restore the place to its former glory, but so far has yet to come up with the necessary funds.

“See that second story balcony, the bedroom? That was Sandy’s room, right there,” Crawford says. West loved animals, he explains, and had a particularly soft spot for the pigs. From that window, she would throw food down for the peacocks, Sicilian donkeys, and Ossabaw hogs she kept as pets. “They knew her voice. They’re the most intelligent of all domestic animals,” Crawford says. “They make a dog look stupid.”

Crawford tells me how he once raised an orphaned feral pig of his own, called Little Boy. He had the piglet litter box-trained in a week. By the time Little Boy was an adult, his border collie and other dogs had recognized his superior intelligence. “The pig became the leader of the pack,” Crawford says. “I like hogs a lot. They’re not fierce or aggressive no matter what people say, what hunters want to make you think. If you chase them with dogs and corner them, then of course they fight back.”

As for West’s pigs, there were generations of them. The last two, which everyone seems to remember best, were Paul Mitchell and Lucky—so named because he escaped from the talons of a hawk as a piglet and survived the experience.

West had big dreams for Ossabaw Island, but not all of them panned out. In the 1960s, she launched the Ossabaw Island Project, an artists’ residency program. One of the requirements for participants was that the artists, writers, and everyone else needed to sit down together every evening at West’s grand dining table. “It was always a mix of people,” Crawford says. He remembers how there were many nights where the crowd would stay up late, sipping “adult beverages” and exchanging ideas.

Crawford leads me up to the window, through which we can still see the interior of West’s mansion. Through the gloom, I squint to try and glimpse the taxidermied heads of gazelles and other trophies from family hunting trips. Save for the fine film of dust on the furnishings, it looks as though she just stepped out for a minute.

In 1970, West launched The Genesis Project, a residency for young students and creatives in the earlier stages of their careers. From the beginning, the interdisciplinary colony had a whiff of utopian idealism to it. In the program, graduate students lived in thatched-roof treehouses and buildings in a settlement known as Middle Place.

One of the participants in the very first year of The Genesis Project was Brisbin, then a young biologist who would end up dedicating much of his life to the study and preservation of the Ossabaw hogs. At the time, Brisbin had recently finished his PhD and was studying animals along coastal areas for traces of radioactivity. The more Brisbin and his fellow graduate students looked into the Ossabaw hogs, though, the more they realized there was something strange about them.

“We looked at the pigs on Ossabaw and said, ’They look different,’” Brisbin says. “Rumor had it that Ossabaw was the only island where the pigs were totally free of contamination with hybridization with modern domestic pigs.” Later DNA evidence found that the Ossabaw hogs were a clear genetic echo of their long-lost European ancestors, the Black Pig of the Canary Islands.

“We all rejoiced,” Brisbin remembers. “That confirms, we thought, the fact that these pigs are different from the other pigs in the Southeast because they are pure genetic descendants of the original Spanish pigs of the 1500s.”

By the 1970s, the West family fortune was waning and the future of the island was already shifting. In an effort to pressure West into selling her land for development, the state of Georgia ramped up taxes on Ossabaw Island. West was adamant that she did not want her family home to be turned into hotels and condos, but she was running out of options.

In 1978, she accepted $8 million (approximately $35.9 million today) for her beloved island—far less than its estimated value—provided that the state observed a strict set of conditions. On June 15 that year, the state officially recognized the island as a Heritage Preserve, stating that “Ossabaw Island shall only be used for natural, scientific, and cultural study, research, and education, and environmentally sound preservation, conservation, and management of the Island’s ecosystem.”

“I love this island so much that I would do anything to save it,” West said in a 2011 interview with Atlanta magazine. “I have no faith in the public.”

That means that unlike neighboring Tybee or Jekyll Island, Ossabaw Island has neither paved roads nor regular ferry service—and it never will. And while its beaches, by Georgia law, are open to anyone able to sail to them, they’ll never hold resorts or other recreational development. To access other parts of the island, visitors need to apply for a day permit, or visit during one of the island’s public events each year.

There was just one issue. “[Mrs. West] called me and said, ‘Brisbin, you’re the pig person and you’re the ecologist wildlife management person,’” Brisbin recalls. “‘Our lawyers need you to look at this contract and see if it looks all right, because you know how much I love my animals.’”

Brisbin read over the contract. “It simply said, by law, that Ossabaw Island had to be maintained in its ‘natural state,’” he says. “And that sounded good to me. It sounded good to everybody I talked to, but we got outsmarted.”

It quickly became clear that while West’s deal may have protected the island from commercial development, it couldn’t protect the hogs of which she was so fond. In the 1980s, the DNR started ramping up efforts to control the island’s pig population in earnest, much to West’s personal distress. Between organized hunts and trained officers with high-powered rifles, there was talk of eradicating the hog population entirely.

It’s true that feral hogs breed like rabbits and can cause an astonishing level of destruction. Some level of culling was necessary to keep the population from running rampant, but without definitive population surveys, it was impossible to say how much. And the solutions on the table, including high-tech traps and poison—which remains prohibited—made the researchers uneasy. In its efforts to save Ossabaw’s other species, the DNR gave no thought to what they might be about to lose forever.

“Whatever the Ossabaw hogs came from no longer exists, at least no longer in that form,” says Jeannette Beranger, a senior program manager at the Livestock Conservancy who managed the studbook for the breed for years. “There are all kinds of things that these genetics represent that we can’t get back if those animals disappear.”

In 2001, “a man named Michael Sturek called me out of the blue,” Brisbin recalls. Sturek had come across Brisbin’s research and he, too, was fascinated by just how much fat these pigs could store on their bodies.

“Thank goodness for Brisbin,” Sturek says. “Brisbin wrote this letter to a journal called Science saying there are these pigs on Ossabaw Island and they develop diabetes and the DNR wants to eradicate them from the island. So he was asking for permission to get some off the island and preserve the breed.”

Sturek’s interest in Ossabaw hogs was really about people. He’d been studying the impact of diabetes and its impact on cardiovascular disease in humans for years and was growing frustrated. Scientists have historically relied primarily on mice to study diabetes and other diseases, since they’re inexpensive to raise and reach maturity quickly. But that strategy hasn’t been working.

“There have been over 200 different cures for diabetes in mice and every single one of them has failed when tried in humans,” Sturek says. It was time, he believed, for researchers to focus on a different mammal.

“Pigs are so much like humans in a lot of ways,” Sturek explains. Pig and human hearts are so similar that scientists have experimented with using them for humans in need of a transplant. “Their heart looks very much like a human’s. Their immune system is similar to a human’s. And the nature of obesity in pigs is like human obesity also.”

Sturek honed in on one particular fact: Ossabaw hogs do not produce insulin. That means that the same intramuscular fat that makes them adept at surviving the winter, also makes them prone to developing type 2 diabetes under the right circumstances. And unlike most domestic pigs, which can easily reach 300 or 400 pounds, Ossabaws are closer to an average human body weight.

For Sturek, the search to find a cure is personal. He had been studying cardiovascular diseases for years when his three-year-old son was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. “It was pretty traumatic for us,” Sturek says, who knew all too acutely what the ramifications of the condition could be.

“People who have diabetes, when it’s poorly controlled, have a real tendency to get heart disease and other complications,” he says. Although Sturek’s son Josh is healthy and successfully managing his diabetes, the race to find a cure continues. “My commitment was to do everything I could to do everything to prevent heart disease in people with diabetes.”

Codey Elrod, a DNR official who lives on the island, once said in an interview with Savannah Morning News, “My job is to kill hogs.” Along with an AR-15 semi-automatic rifle, Elrod’s arsenal includes traps, thermal-imaging scopes, and a pair of dogs. Every year, when loggerhead turtles swim up to lay their eggs from May to September, Elrod is ready. The hogs come at night, ready to feast, and he is often the lone person defending the nests. Any hog that shows itself gets shot on sight.

“This time of year he spends a lot of time on the beach, but he’s out at night,” Crawford tells me as we swing by the shoreline. In the process, we run into a patch of uprooted earth stamped with cloven hooves, causing the pickup truck to lurch violently. “[The hogs] would be glad to eat anything on the island here. They have to be controlled on the beaches because they will dig up and eat sea turtle eggs.”

The culls have arguably been a benefit to other creatures that share Ossabaw Island’s fragile ecosystem. In 2004, the entire state of Georgia had about 400 loggerhead nests—a number Ossabaw Island alone now has in a single season. Since the DNR began actively protecting Ossabaw Island’s nests with wire netting and warding off predators, the populations have stabilized. Last year, a quarter of a million loggerhead sea turtles laid their eggs on Georgia’s beaches.

But Brisbin remembers his growing sense of alarm as the culls intensified. “[Sturek] said, ‘We need to get pigs off that island if they’re going to poison them and shoot them,’” he says.

In terms of preserving the gene pool of this heritage breed, there was an even bigger threat. In order to boost the size of the hogs for game hunters, someone had introduced a Hampshire boar onto the northern part of the island. To this day, Brisbin remains convinced that a Eurasian boar made its way into the mix too.

“They really ruined everything, because they opened up the island to public pig shoots, but the public didn’t like to shoot these little 90-pound scrawny things. They wanted a big pig with wild tusks that they could mount over their bar,” Brisbin says. “All of a sudden, Ossabaw pigs are having little striped piglets, which is a sure sign that they’re hybridized with wild boar.”

In the year 2001, the striped piglets still all seemed to be concentrated on the northern part of the island. Pigs are proficient swimmers with a tendency to roam to wherever food lies; meaning there was no guarantee how long the pure Ossabaw hogs would last. “What a stupid thing to do,” Brisbin says angrily. “It was the only population of wild pigs that was free of domestic hybridization.”

Back on the mainland, there were already a number of farms purportedly raising Ossabaw hogs, some of which claimed to be able to trace their lineage to pigs removed legally from the island in the 1970s. Yet none were able to prove the pedigree of their pigs sufficiently to meet Brisbin and Sturek’s standards. “That’s why we decided to go right to the island to get our hogs,” Sturek says. If they wanted to track down real Ossabaw hogs, there was no time to lose.

In 2002, Sturek made his first trip to the shores of Ossabaw Island in pursuit of its elusive swine. For weeks prior to that voyage, a local named Roger Parker had been diligently laying traps all over the island for a month. By the end, he had captured 97 live, squealing hogs, all kept in an enclosure for the team of researchers, led by Sturek and Brisbin.

There was just one big problem: it was illegal to take a live Ossabaw hog to the Georgia mainland. Ossabaw hogs can carry pseudorabies, vesicular stomatitis, and brucellosis, all of which are dangerous for their domestic counterparts. Out of fears of cross-contamination, the DNR has had a strict ban in place for decades.

The state of Georgia granted the researchers permission for their endeavors, but only provided they jump through considerable hoops to prove that their hogs were disease-free. That meant individually testing each hog. “[The animals] were enclosed in a pen, so we could more easily grab a pig and wrestle it to the ground to get a blood sample,” Sturek recalls.

Tranquilizer dart guns proved useless, which meant that the only option was to get up close and personal with their quarry. “The more practical thing is you put the animal on its back and with a needle you get into the jugular vein,” Sturek says. “It would take four people to hold and one person to draw the blood.”

Brisbin remembers going to extraordinary lengths to keep from taking any diseases to the mainland. The researchers became pig doulas, taking pregnant sows into West’s mansion and housing them in the bathrooms. “You let her have her little pigs in the bathtub,” Brisbin says. “[They] were delivered by cesarean, by the University of Missouri veterinarian. All these little pigs, therefore, were uncontaminated by any of these diseases.”

With 26 piglets testing negative for all three diseases, the project was done. The team had to euthanize the rest, which in one case led to an impromptu pig roast. If you “wanted to win a barbecue cook-off,” says Brisbin, there would be no way to beat an Ossabaw hog.

Even after all of these precautions, as the time approached to actually get the hogs off of the island, Brisbin was growing increasingly apprehensive about their operation’s chances. Representatives of both the Georgia and South Carolina Departments of Natural Resources weren’t budging: no live Ossabaw hogs were to touch ground on their shores. In order to get to the landlocked research facility at the University of Missouri, Brisbin took a gamble.

In the quiet before dawn on a Sunday morning in March, when no one was watching, the researchers snuck their precious, living cargo onto a barge. They navigated their way back through Hell’s Gate, propelled by a boat named the Eleanor, after West, then ushered the pigs into an 18-wheeler truck and gunned the engine until they were out of the state.

“Their little feet never touched the soil of the state of Georgia,” Brisbin says. “It went from the barge to the ramp to the back of the truck to the South Carolina state line, and off they went to Missouri. And this became the foundation of the only genetically pure population of wild Ossabaw pigs in captivity.”

The benefits of the great hog-napping of 2002 have been enormous, both for the scientific and culinary worlds. Thanks to those 26 genetically pure pigs that made it off the island, the Ossabaw hog breed survives, at least in exile.

Sturek and his colleagues have sent specimens as far as Denmark, and currently have roughly 300 swine living in a biomedical grade facility in Crawfordsville, Indiana, where they eat a diet high in fructose, fat, and calories to encourage them to develop diabetes Already, they’ve been able to provide the researchers with valuable information and, perhaps one day, these findings will lead to a cure.

That source of genetically pure Ossabaws has been a boon for chefs as well. After trying and failing to obtain permission to get them off the island itself, Peter Kaminsky purchased 23 Ossabaw hogs from Sturek and his associates at the research center at the University of Missouri. In his book, Pig Perfect, he describes the taste as “waves of exquisite porkitude.” In an interview with Salon, Kaminsky declared the Ossabaw hog a “brandeable pig—like Wagyu beef, a foodstuff with a story, just as wine has a story.”

Some of Kaminsky’s hogs ended up in the hands of Daniel Boulud, the triple-Michelin-starred chef, and several of his fine dining chef compatriots, who were blown away by the resulting charcuterie. While purebred Ossabaws are still a rarity, they have a devoted following among some of the most critically lauded chefs throughout the American South.

“The meat-to-fat ratio means it’s an amazing hog to roast,” says chef and farmer Matthew Raiford, who writes about how to cook them in his book Bress ‘n’ Nyam: Gullah Geechee Recipes from a Sixth-Generation Farmer. “It’s not just juicy—it’s succulent.”

Much of Raiford’s work centers on hyperlocal foods with terroir and a sense of place. And when it comes to pigs, he says the Ossabaw hog is a Georgia hog in the truest sense. “That hog is a hog in which the genetics have been sitting there for over 500 years,” he says. “I’ve got to give some respect to this [animal], because it’s been around for a very long time.”

The Gullah Geechee, the descendants of enslaved Africans forcibly brought to Georgia and surrounding Southern states, have a long tradition of using every part of pig. “Any hog inside of Gullah Geechee cooking is a community effort,” Raiford explains. “Many moons ago, it was all about the community coming together and it was also about using the whole hog. It’s about taking all the pieces and using them as you can.”

Raiford sources most of his Ossabaw hogs from a small, sustainable farm in Milledgeville, Georgia. He has cured their jowls into guanciale “just using salt, sugar, spices and time” and pit-smoked whole hogs rubbed with salt and pepper, along with a touch of smoked paprika, garlic, and a little ginger for 12 hours, until the skin glistens and shatters like the top of a crème brûlée.

As for the fate of the hogs on the island itself, that remains precarious. Although the DNR has largely given up the hope of eliminating the population altogether, that isn’t for lack of trying. The only thing stopping them from wiping out the hogs on the island is the hogs themselves. So the pigs remain in an ecological stalemate with their hunters.

That equilibrium could always shift or the DNA of other breeds could irreparably contaminate the gene pool on the island. Someday soon, if not already, the only pure Ossabaw hogs in the world may exist in carefully controlled colonies.

But Ossabaw hogs living in labs or on heritage farms such as Autumn Olive Farms in the Shenandoah Valley or Cane Creek Farms in North Carolina are never going to be the same as wild animals. The hogs of Ossabaw Island have run feral for 500 years. Their genome may trace back across the Atlantic, but their evolution is inextricably linked to the conditions of the island itself.

“Now that they’re off the island, it’s not nature shaping them anymore, it’s humans, because they’ve got an easier life. Ultimately, they’re going to change,” says Beranger of the Livestock Conservancy. After several generations of captivity, they have begun to lose to some of their unusual adaptations that helped them thrive in the wild.

Sturek has some optimism that their tenacity for survival in Ossabaw Island’s specific conditions might protect their genetics; a Eurasian or a Hampshire boar would be less equipped to deal with the distinctive challenges of this wondrous, hellish island.

That was why Sturek and his fellow researchers from Indiana ventured back to Ossabaw Island in 2022: to see the environment in which the hogs lived, largely undisturbed for so many generations. It was why I went too, to see this otherworldly place and try to better understand its strange four-legged inhabitants.

On the morning I visited, I was standing on the mainland dock when Crawford shouted, “Hogs!” Across the water was a large family of hogs silhouetted against the thick marsh grasses. We were too far away to alert them to our presence, but as I watched through the binoculars, their dark coats began to recede. Before long, they were gone, a fading apparition in the rising summer haze.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook