This Christmas Dessert Caused a Decades-Long Rivalry Between Two Countries

Two historians are trying to track down pavlova’s origins once and for all.

For the last few years, Annabelle Utrecht, a historian from Australia, and Andrew Paul Wood, an art historian and writer from New Zealand, have been in the middle of a food feud. The object of their disagreement: an airy cream- and fruit-topped meringue dessert called pavlova. Both Australia and New Zealand claim that it originated on their soil, but Utrecht and Wood decided to settle the question once and for all. They were “determined to prove each other wrong,” says Utrecht.

Both historians dove into the history of pavlova, and what they found—that meringue cakes topped with whipped cream and fruit originated in neither country—provides a fascinating window into how food travels around the world, and how it transforms in the process.

Pavlova is not the only food the two countries claim as their own. “There are similar arguments about meat pies, Anzac biscuits, and Lamingtons,” Wood says, noting that Australia and New Zealand have a “frenemies” relationship dating back to the First World War.

Professor Paul Freedman, who specializes in the history of cuisine at Yale University, calls international culinary rivalries “an assertion of identity.” When one country “owns” a dish, anyone else making it must prove their bona fides to serve it, he says. So, for example, if pavlova is from New Zealand, then their version is authentic, and all others are mere knock-offs.

Numerous attempts have been made to prove the origins of pavlova before. In 2008, Helen Leach published her book The Pavlova Story: A Slice of New Zealand’s Culinary History, where she documented 21 recipes in New Zealand cookbooks for pavlova before the first recipe appeared in Australia in 1940. The Oxford English Dictionary had also attempted to settle the matter, when it noted that the first recorded pavlova recipe was published in New Zealand in 1927. Out of the two countries, New Zealand seemed to be the winner.

When Utrecht and Wood set out to research this question, they traced pavlova back much further, to its roots. They found that Duryea’s Maizena (a cornstarch brand) had published meringue recipes containing cornstarch starting in the 1860s. This cornstarch was imported from the United States to both New Zealand and Australia, and dessert recipes from this company could be found in New Zealand newspapers from as far back as the 1870s. The recipes may have inspired an early meringue dessert in the Southern Hemisphere, that was later renamed pavlova.

Then, tracing the history of meringue recipes in the United States, they discovered that they likely originated from European petit meringues from the 17th and early 18th centuries, which later became a more complex, larger dessert known as Spanische windtorte in Austria. Instead of meringue topped with cream and fruit, like the pavlova, the Spanische windtorte has cream and fruit inside the meringue. Otherwise, it looks almost identical. As German-speaking immigrants moved to the United States, they brought recipes for similar desserts such as schaum torte and baiser torte with them. Soon, meringue had become popular enough to find its way to New Zealand.

The search for the origins of this dessert were complicated by the name. The pavlova was named after Anna Pavlova, a famous Russian ballerina who toured in Australia and New Zealand in 1926, and this is not the only dish that was named in her honor. Strangely, Utrecht and Wood discovered a dessert named “Strawberries Pavlova” from 1911, before Anna Pavlova had even arrived in New Zealand. Even more unexpected, the Strawberries Pavlova was unlike any others: It was a sorbet dessert, without meringue.

Even as people search for pavlova’s roots, it has become increasingly popular, especially at Christmas. In both countries, Christmas desserts have traditionally followed the path of their colonial origins, leaning towards fruit cakes, plum puddings, and other spiced dishes. Freedman says that pavlova doesn’t quite fit the usual Christmas dessert archetype. It’s “not an especially elaborate dessert, it doesn’t take days to make, and it’s not like plum pudding which is something that can sit around for a month before you serve it,” he says. In Australia, it has even overtaken Christmas pudding as the favorite Christmas dessert.

Utrecht explains that the “lightness of the pavlova counterpoints the heaviness of traditional Christmas dinners and rich desserts like mince pie or plum pudding.” Then there’s the fact that, for Australians and New Zealanders, Christmas falls at the height of their summer. “Let’s face it, on blazing hot days in the Southern Hemisphere, pavlova is an acceptable latitude of airy sweetness,” Utrecht says.

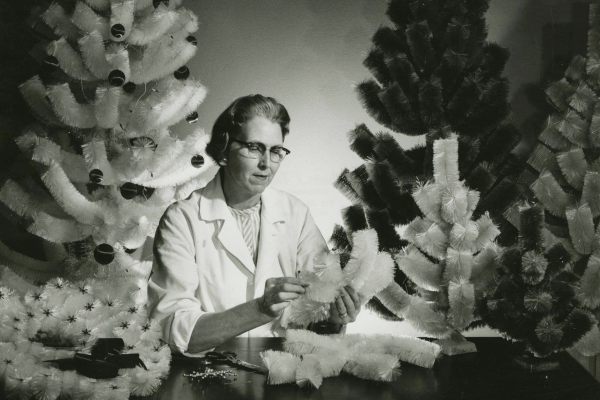

The pavlova-Christmas connection goes back to 1934 in New Zealand, when the Municipal Electricity Department in Papanui, Christchurch, included “Pavlova Cake” in a cooking demonstration that they provided in Papanui’s Memorial Hall. The demonstration was intended to “introduce electrical cookery to Kiwi women,” says Utrecht, “and the meringue in pavlova was the perfect candidate for using an electric beater.”

In Australia, a similar dessert (though not named pavlova) was Emily Futter’s “Meringue with Fruit Filling,” published in a Christmas recipe column in December 1921. Utrecht also notes the United States First Lady Bess Truman and the women of the of the U.S. Diplomatic Corps “incorporated a little cookery booklet within their 1949 Christmas card dispatch,” which included the personal pavlova recipe of Lady Berendsen, the wife of the New Zealand Ambassador to the United States.

It’s easy to see why pavlova became a Christmas classic. According to Utrecht, it’s a convenient and economical dessert to make. “There’s nothing wrong with that, when it comes to reducing Christmas pressure,” she says. For these reasons, it is cherished by New Zealanders and Australians alike. According to Wood, the argument over pavlova just adds more zest to Trans-Tasman relations. “Families fight,” he says. “Having things to argue about makes us closer.”

At this point both Utrecht and Wood have “pretty much wrapped up [their] pavlova-mission,” says Utrecht, adding that a book on the subject is in the works. Utrecht currently is making historical meringue torte recipes “in an effort to understand them better,” posting pictures of these historical desserts on Instagram.

Wood, on the other hand, isn’t even a big pavlova fan. Since he started his research on the dessert, “people keep insisting I make them for events, even though I always overcook them,” he says. “Candidly, I have come to loathe pavs a bit.” Wood is currently working on a book on the history of the occult and esoteric in New Zealand, which, he notes, is “probably about as far away from pavlova as I can get.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook