A ‘Weird’ Ancient Marine Reptile Surfaces Thanks to the ‘Bone Biddies’

The unique plesiosaur defies the fossil rulebook—just ask the “paleogrannies” who prepared it for study.

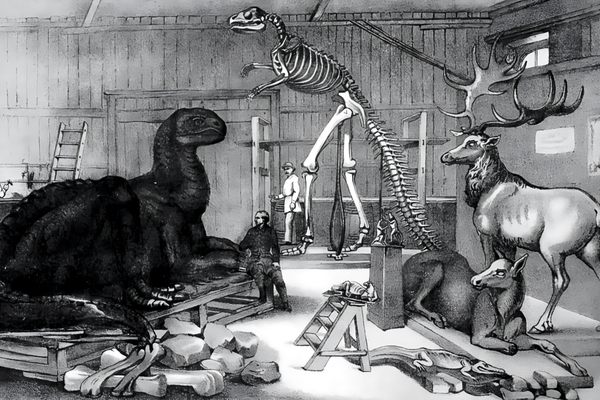

Roberta “Bert” Smith, 68, and her friends spend a good deal of their time surrounded by bones. With pneumatic engraving tools, dental picks, and paintbrushes, they scrape and etch and slough away millions of years of dirt and debris from femurs and skulls, jumbles of teeth and crushed ribs. Beneath their fingers magnificent beasts emerge: massive, horned torosaurs, a ferocious marine reptile known as a mosasaur, and now, another ancient marine reptile: a plesiosaur that is rewriting an evolutionary story we thought we knew. Smith, a self-described “paleogranny,” is cheerfully humble about their important contribution to science. “It’s our little quilting bee. We just sit around and visit while we work.”

Based at the Paleon Museum in Glenrock, Wyoming, the largely-retired group of volunteer fossil preparators have dubbed themselves the Bone Biddies (“I’m a Bone Buddy,” notes Don Smith, 70, Roberta’s husband and a team member). The small museum, just east of Casper, may not be on every paleonerd’s radar, but it’s home to an outsized collection of important fossil finds from across the state—including the plesiosaur that the Bone Biddies (and Buddy) affectionately refer to as Harold. And these days, Harold is making a splash in scientific circles.

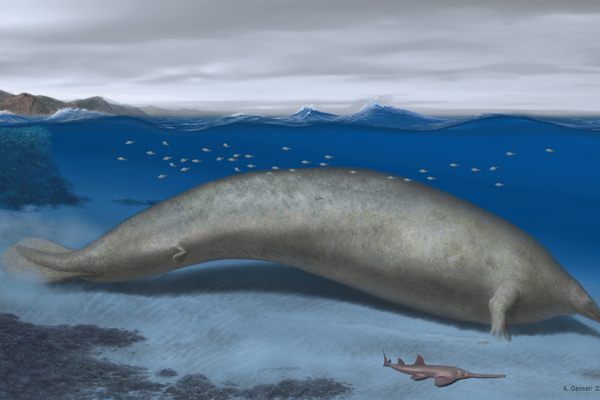

Originally unearthed in the 1990s but formally described only this week in a paper published in the peer-reviewed journal iScience, Harold, about 24 feet long, is now officially known as Serpentisuchops pfisterae. About 70 million years ago, the Western Interior Seaway—an inland sea that once swallowed much of the American Great Plains—covered what’s now Wyoming. S. pfisterae swam through its warm, tropical waters with some unique features.

Paleontologists had previously documented “two flavors” of plesiosaur, says lead author Scott Persons, a paleontologist at the College of Charleston: animals with long necks but small heads and short jaws, and another group with short necks and long, crocodilian-like jaws. Harold, however, is something in between, with an unusually long neck—32 vertebrae, compared to a giraffe’s seven—and an elongated snout with impressive jaws, similar in some ways to those of a modern gharial.

“That makes our animal really weird,” Persons says. Other fossils from this period in Wyoming’s deep past confirm that Harold shared the sea with more typical plesiosaurs. Persons and his coauthors believe S. pfisterae’s long neck, long jaw strategy allowed it to create its own ecological niche, going after prey other plesiosaurs didn’t.

Plesiosaurs with short necks but big jaws, for example, tended to hunt larger fish. But, while Harold’s teeth are substantial, they’re not serrated like those of many big-game predators. “They’re not teeth you would use to do a lot of damage to something,” says Persons. Instead, the teeth fit together very tightly when the jaw is shut. “That’s the dental weaponry for grabbing hold of stuff that is small and slippery. You’re not worried about being overpowered, you just need to hold on to it.”

Persons and his colleagues believe Harold was going after smaller fish, probably by swishing its neck quickly to one side and clamping shut its jaws. Other anatomical features, such as the shape of its vertebrae and large areas for neck muscle attachment, support that hypothesis.

The weirdness of Harold came to light over roughly two decades of careful work by the Bone Biddies; the Wyoming spot where it was found is a barren badlands that’s infamous for crusty, cruddy calcite crystals that adhere to fossilized bones in a matrix hard as concrete. “It’s in some nasty sediment,” says Persons. The challenge was something the Bone Biddies relished, says Roberta Smith.

“When the fossil first came in, all the Bone Biddies were sitting around, very carefully working on it with paintbrushes, removing the matrix bit by bit, and a beautiful tooth emerged,” she recalls with both awe and delight.

For Smith, a Bone Biddy for a quarter-century, the work appeals to her for the same reason fossils draw students into paleontology. “I love learning,” she says. “With each bone, we learn something.”

Fellow fossil preparator Lorna Keyfauver, 74, has been volunteering at the Paleon for about 15 years. In addition to various pieces of Harold, she has prepped Carol the torosaur and other big finds that now live in the museum’s exhibit hall. “It’s a mystery, chapter after chapter, until you come to the conclusion,” Keyfauver says of the prepping process. “If you like puzzles, the brainwork, this is where you need to be.”

The Paleon Museum is one of several institutes and labs that rely on volunteers to do the time-consuming, often-tedious grunt work of fossil prep. Bureau of Land Management paleontologist Alan Titus, whose Utah-based lab has handled a number of important Cretaceous finds, including multiple tyrannosaur fossils from a single bonebed, says volunteers do crucial work that is “exacting and tedious at the same time.”

Given the time-consuming nature of the work and the tight budgets of most paleontology labs, “the program simply couldn’t do its job without them,” Titus adds. “Most of them are retired and looking for community, so we’re happy to provide that for them, and get some serious help in return.”

There is not a lot of glory in fossil prep—but there is some. Titus says his team decided to name a new, as-yet-unpublished mosasaur after a long-time volunteer, Steve Dahl, in recognition of his contribution to its collection and preparation. And, back at Glenrock, there is tremendous pride over Harold the weird plesiosaur among the Bone Biddies and Buddy, perhaps even more than for other fossils they’ve brought to light.

When Harold was still in its early stages of preparation, Persons visited the Paleon on an elementary school outing. “This is actually the museum that took me on my very first dinosaur hunting trip,” he says. In addition to its exhibits and busy prep lab, the museum runs field digs at local sites rich with the fossilized remains of Late Cretaceous ecosystems. It was there that Persons found his calling. As a teenager, while serving as a docent and in other volunteer roles, he watched the Bone Biddies strip away the hard sediment and tenacious calcite hiding Harold from the world. Persons now serves as the museum’s research curator, and has initiated a program to bring his students from Charleston to Wyoming each year to dig—and to pick up a few prep tips from the Biddies.

“He’s come full circle, from coming here when he was young and deciding he wanted to be a paleontologist to coming back now, bringing his students with him,” says Don Smith. As for the Bone Buddy, a former executive director of the museum who’s now happily chipping away at retirement, he has no plans to hang up his paintbrush and dental pick any time soon.

“There’s not a lot of us preparators in the world,” Smith says. “It’s a unique hobby, and we feel pretty proud of him.” (As to whether he’s talking about Persons or Harold, the answer is yes.)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook