The Hunt for an Elusive Florida Shipwreck That Killed 41 Enslaved People

Searching for the slave ship Guerrero, the nonprofit Diving With a Purpose has also trained scores of young Black men and women to find and tell stories once lost to the waves.

Carysfort Reef was dark under the new moon. Coral tentacles undulated with the changing tide, while black-tipped sharks patrolled for lobster, twisting their snouts into cracks and crevices.

Then, a crash! The hull of the Guerrero ripped through the corals. On impact, its mast snapped, plowing through a hold packed with men, women, and children. As water rushed into the breached hull, screams could be heard across two miles of ocean. Ultimately, 41 of the 561 captive Africans aboard would die on that stormy night in 1827.

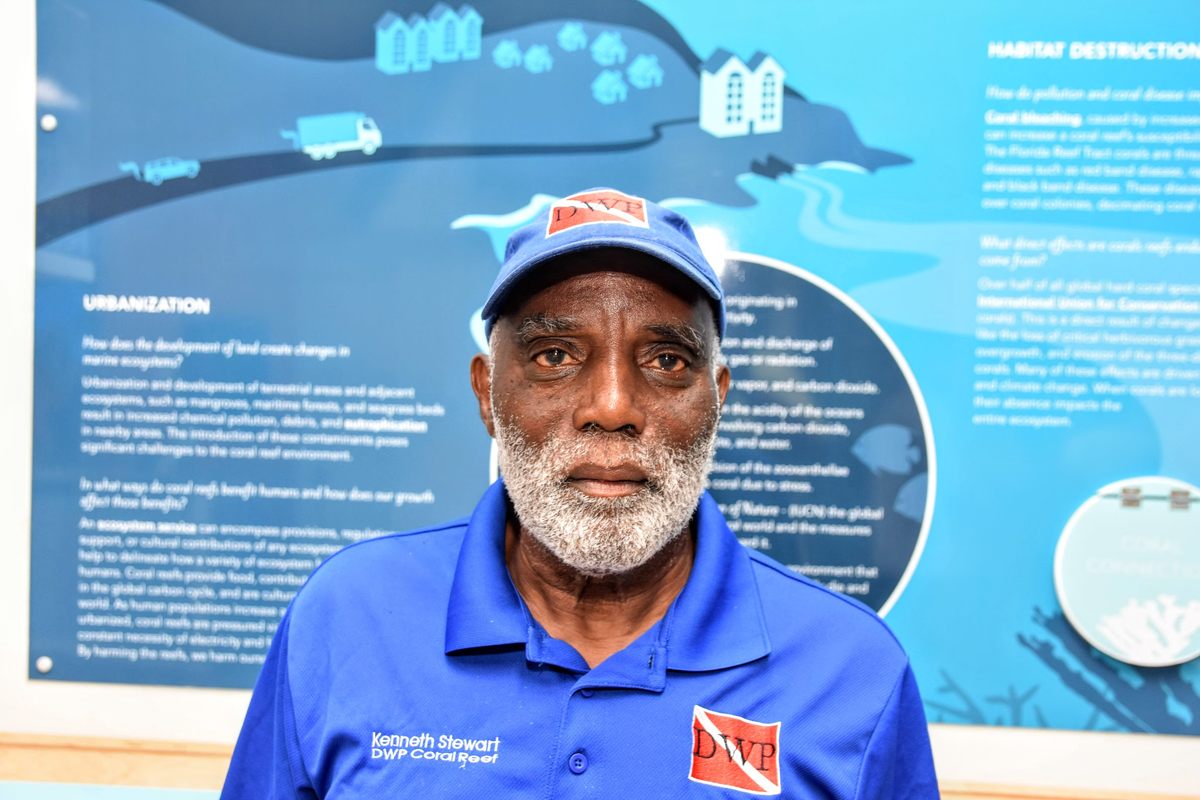

Nearly 200 years later, those same blue-green waters are now sparkling and calm under the hot sun. A group of mostly African American scuba divers, led by Ken Stewart, chat in excited anticipation as they check their gear. They’ve plunged into the northern Florida Keys’ Biscayne National Park dozens of times before in their search for the remains of the pirate slave ship Guerrero. Finding it would make history: It would be the first wreck of a slave ship in U.S. waters that went down with enslaved people aboard. The clock is ticking, however. This will be one of the group’s final attempts.

“I never went to college, you know,” says Stewart, cofounder of Diving With a Purpose (DWP), an African American maritime archaeology and conservation nonprofit. “I barely got out of high school. I was not involved with history. But this one story just really stuck with me. It set me on this journey.”

Stewart’s odyssey began about 20 years ago, when he first heard about the Guerrero—from me. We connected when I was looking for Black divers to interview for a documentary about the ship and the people it carried. The story instantly captivated him—but it was something two of his young diving students said about the Guerrero that kicked off an epic hunt that would last for decades.

At the time, 14-year-old Chris Cannon and his fellow student Marcus Johnson said that they were personally motivated to learn what their ancestors had experienced, but that most teens felt, as Cannon put it, “Knowing about that stuff is really not important in our generation.” His words caught Stewart’s attention and led the master diver to wonder: Would teaching young people their history make a difference in their lives?

Fueled by the need to find out—and to find the Guerrero—Stewart teamed with Biscayne National Park archaeologist Brenda Lanzendorf. He created DWP to train Black divers in maritime archaeological techniques to ensure they would be involved with documenting it if it was found. And he embarked on a quest to teach his diving students about the African Diaspora and today’s lingering impacts of the Middle Passage, the transatlantic voyage that enslaved Africans were forced to endure.

Since then, DWP, later joined by its offshoot Youth Diving With a Purpose, has searched for the Guerrero around the Florida Keys nearly every year. Lanzendorf was a driving force in the early years but died in 2008.

In 2017, a National Park Service-funded magnetometer survey conducted in the southern third of the park detected more than 1,000 anomalies. Any of them might be a piece of the Guerrero. Since then, DWP and Biscayne archaeologists have systematically dived on them, and found artifacts such as bar shot and copper spikes, but nothing identifiable to the pirate ship specifically. This summer they’re set to dive on the final 70 anomalies found during the survey. After that, their options will be exhausted.

Says Stewart: “We’re closing the chapter on the Guerrero one way or another.”

The final voyage of the pirate ship Guerrero began somewhere off Africa’s western coast when Captain Jose Gomez and his crew likely kidnapped people already held captive on two other ships. The Guerrero’s destination was Cuba, where auctions of enslaved people were still held. Although slavery was legal at the time, the trade of buying and selling people had been banned by the United States and United Kingdom, and British patrols were on the lookout for illegal slavers. Gomez was nearly home free when Lieutenant Edward Holland, aboard the British schooner HMS Nimble, spotted him.

The pursuit was on, heading west through the Straits of Florida. The Guerrero’s copper-plated hull made it one of the fastest ships of its day—but the Nimble, itself a former slave ship, gained ground. A storm pounded both ships with heavy swells and squalls. Darkness fell and a firefight ensued. Then both ships hit the reef. The Nimble’s rudder was destroyed, but the crew was eventually able to free the ship by throwing heavy items overboard. The Guerrero was a total loss.

“You can imagine [Holland’s] thinking at the time,” said historian Gail Swanson in a 2003 interview. “His duty was to save the people on the slave ship from a lifetime of slavery in the Cuban fields, [but] he accidentally ran them to their doom in the waters off of Key Largo. And he could do nothing to assist them; his ship could not sail.”

It was Swanson, an independent scholar, who years earlier began following a string of evidence in dusty archives that led her to uncover the story of the Guerrero. Without her dedicated detective work, the ship likely would have remained forgotten, and Stewart might never have created DWP and YDWP, which have gained international acclaim. Divers trained by the organizations have documented slave shipwrecks including the São José Paquete D’Africa near Cape Town, and assisted in site surveys such as that of a downed Tuskegee Airmen plane in Lake Huron.

But when Stewart began DWP, slave ships and the Middle Passage weren’t popular subjects. “When it comes to archaeology, that type of thing, it’s just not sexy. People want Spanish galleons with treasure and that type of thing” says DWP cofounder and lead instructor Erik Denson. “But it’s a history that needs to be told.”

The Guerrero is, in many ways, a microcosm of that bigger history—it’s one of the reasons Stewart and his team are so driven to locate the wreck. The brutality of the Middle Passage—when tens of thousands of ships like the Guerrero transported millions of people against their will to the Americas over four centuries—is hard to comprehend in both its immensity and duration. It’s vital to understand, however, because of the way slavery shaped our nation and our communities on every level, from the way being severed from one’s ancestry can affect the descendents of enslaved people on an intuitive level to the fact that many of our most powerful institutions exist because trade in human lives made them possible.

“You could almost say that [the Middle Passage] was the most critical factor in terms of this whole brash experiment in colonization succeeding, if that could be called a success,” says historian and artist Dinizulu Gene Tinnie. “Without having this huge unpaid labor force and generator of capital from human trafficking, how would this colonization have ever really taken off?”

The hunt for the Guerrero is important, Stewart says, because it’s a chance to get hands-on with a history that might otherwise seem intangible—and also a history that, ironically, is being censored in the very state where divers are searching for the slave ship.

While many high schools across the U.S. don’t include the Middle Passage in their curriculum, the mostly-teen members of YDWP have been at the forefront of the search for the Guerrero. Twelve high schoolers and college students will be on the final expedition this summer, including three from Cahuita, Costa Rica, where the wrecks of two Danish slave ships have recently been identified.

“They ran aground there and the captive Africans made it up to the hills and started a community,” says Stewart. “So they could be their ancestors. But again, it’s not taught in their schools either. So they’re doing the research on their own.”

As Stewart knows, there is no guarantee this research project—the hunt for the Guerrero—will locate the wreck. Despite historical accounts that provide an unusually detailed description of where the ship went down, hurricanes can scatter and bury its remnants, and shipworms can eat through any exposed wood. And, as current Biscayne National Park archaeologist Joshua Marano puts it, “The reef itself acts like a giant cheese grater…we typically don’t have that much on the surface.”

Marano has worked with YDWP for a decade and remains hopeful that the Guerrero may turn up. “It would be unlikely to find an intact wreck that we don’t know about,” he says. “But it’s not out of the question.”

Without an intact ship, it may be more difficult to identify a wreck as the Guerrero. Many historical wrecks are confirmed by the presence of the ship’s bell, which includes its name—an unlikely item for a covert, illegal pirate ship. Because of the length of time that has passed, it’s almost certain they will not find any human remains. It’s more likely that what’s left of the Guerrero will be puzzle pieces that need to be assembled to confirm the ship’s identity: copper sheathing from the hull, cannon balls with the British broad arrow mark, fired or tossed from the Nimble, or, perhaps most compelling of all, shackles.

There have been a number of promising discoveries. A few years ago, divers located a type of small cannon called a carronade that was, says Marano, “in the right spot [and] approximately the right [age].” But he determined it was probably from one of the reef’s many other wrecks from the 1820s. “There are literally wrecks on top of each other, and with fragmentary evidence it’s very difficult to determine definitively whether or not you found a site.”

Other tantalizing artifacts have been recovered in nearby John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park. Archaeologist Corey Malcolm and divers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found artifacts from the Guerrero’s era, including an anchor, cast-iron shot, and ballast, but nothing definitive.

“If they find something, then we can all compare notes,” says Malcolm, who has collaborated with Stewart and DWP over the years. “We’ll see which site makes sense.”

Even if the Guerrero remains undiscovered, the years-long search for it is already a success. DWP’s volunteers have introduced hundreds of young Black men and women to scuba diving, environmental science, and history, including the story of the 41 people who perished aboard the Guerrero, and countless others on other ships of the Middle Passage.

“Nobody was really telling their story, and there’s so many other cases like that,” says Greg Hood. Hood, a sophomore with a double major in aerospace engineering and psychology at Ohio State, started with YDWP when he was 14 and was recently elected its first president. He’ll be on the expedition this summer. “I believe that our work is important, because we can discover those stories and give those people a voice and amplify those stories to the world.”

The stories of the 520 survivors of the Guerrero are also being heard. After the wreck, the slave ship captain Gomez hijacked two of the three ships that came to the Guerrero’s rescue, and still managed to sell 398 captives into slavery in Cuba. The other survivors were taken to Key West, then to Jacksonville, where they worked on plantations while awaiting presidential approval to return to Africa. While some of the Guerrero survivors died from disease and exhaustion, 92 of them, including at least one child, eventually set foot on African soil—but not that of their homeland. They were taken to Liberia, like others freed from intercepted slave ships, passing their stories to their descendents.

While Stewart still wonders whether teaching young people about their history makes a difference in their lives, the young people who have been diving with his organizations seem to be living proof that yes, it does.

Rachel Stewart (no relation), 27, has been with DWP for a decade. After defending her environmental engineering thesis in May, she’ll join the final search for the Guerrero.

“I love to dive. I love nature, the experience of being underwater, and then adding this extra component of how I’m being connected to history and my ancestors,” she says. “With everything that’s going on in the craziness of the world, we have to continue to tell these stories.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook