The Tomato Pill Craze

How a war over cure-all pills convinced Americans to eat tomatoes.

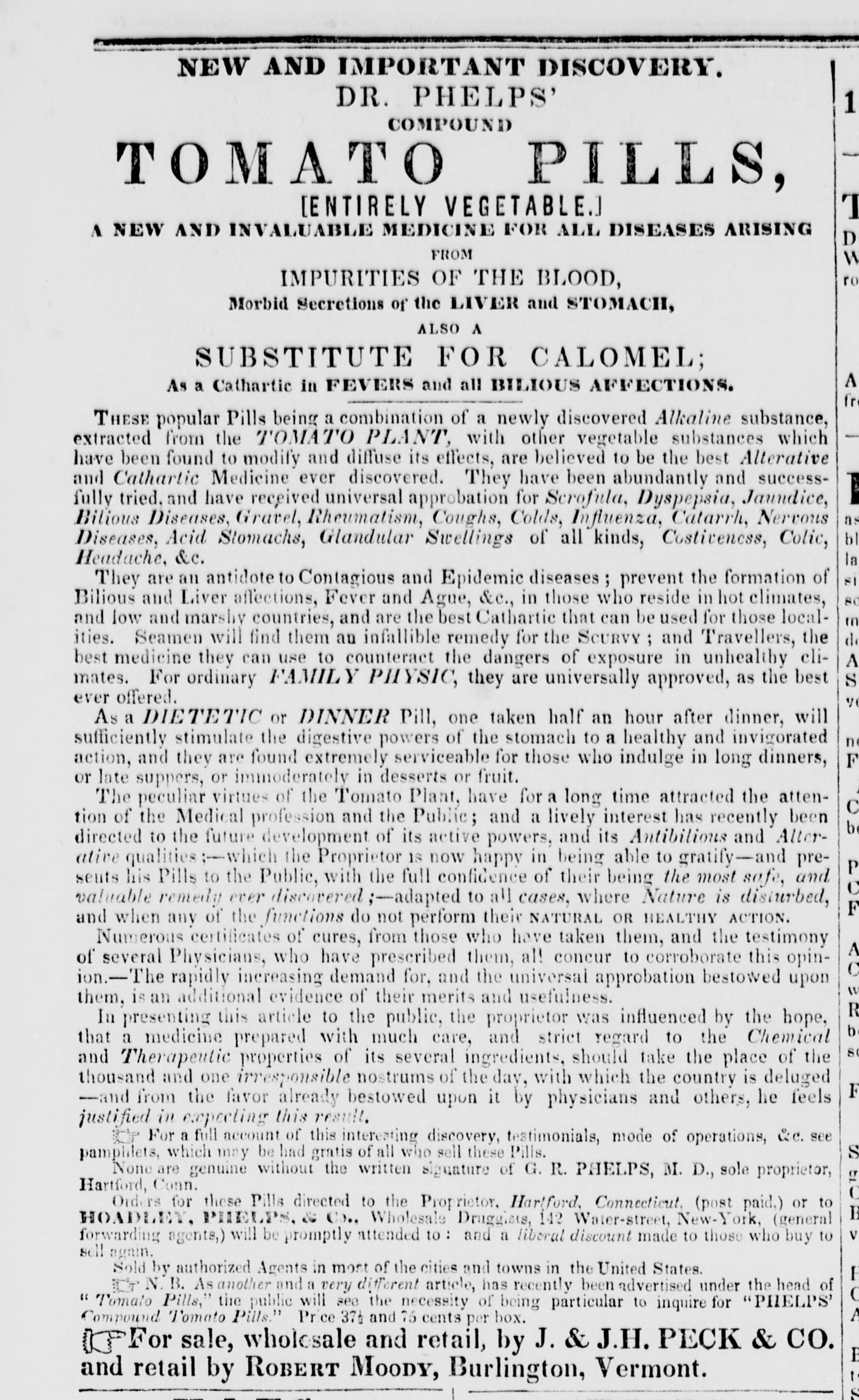

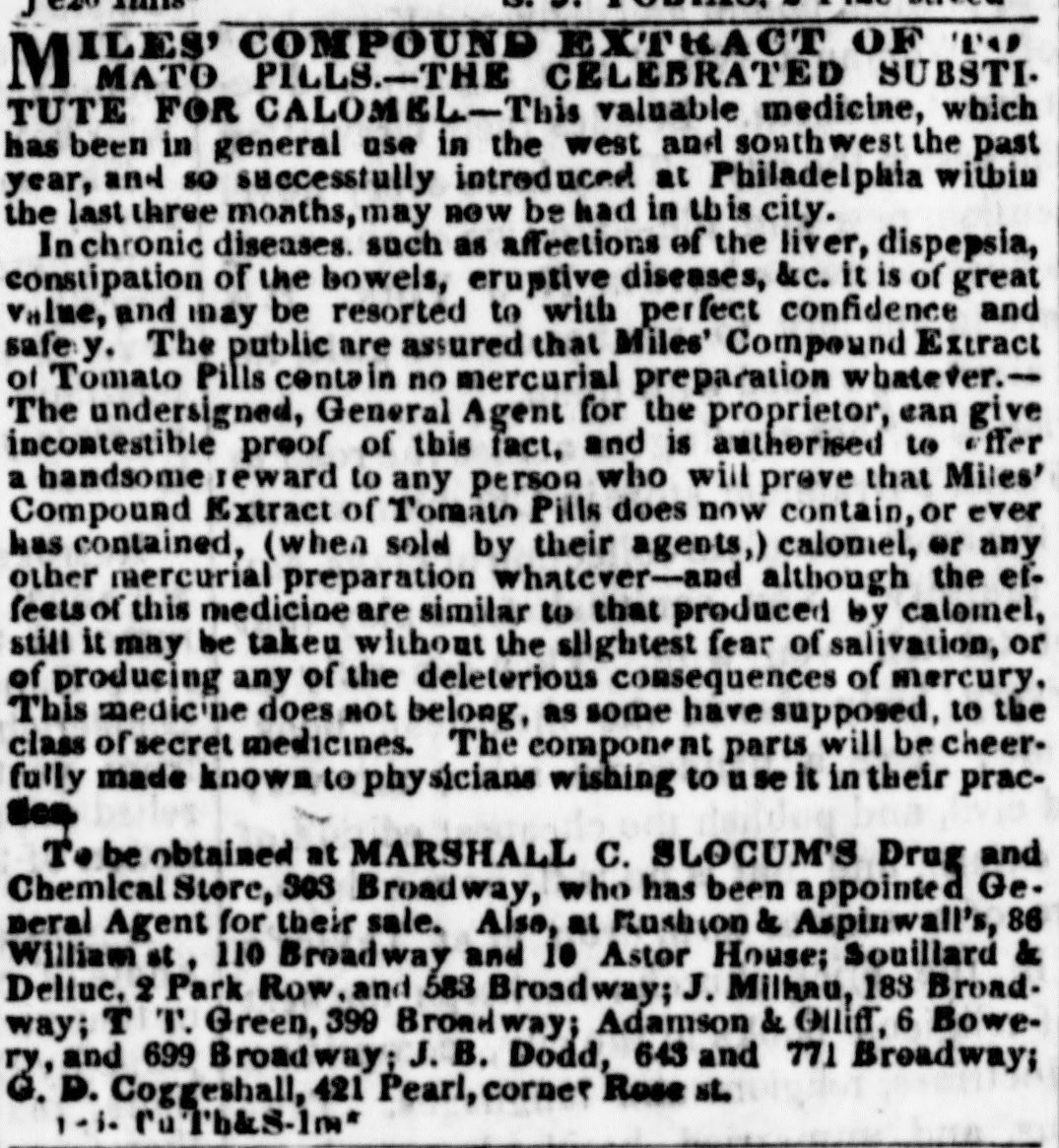

In 1837, newspapers across the country were plastered with ads for a promising new product called Dr. Miles’ Compound Extract of Tomato. It was promoted by Archibald Miles, a Cleveland-based merchant who claimed that his pills had been scientifically tested and painstakingly developed over years to treat everything from indigestion to syphilis. Shortly thereafter, a Dr. Guy R. Phelps (an actual, Yale-trained physician) began doing brisk business selling his own Compound Tomato Pills and promising similar medical results. Miles was livid. An anonymous tirade (likely penned by or at the behest of Miles) was published in a New York paper denouncing Phelps’ pills and claiming they were nothing but a “baseless imitation.” The tomato pill war had begun.

Ads for various vegetable pills claiming miraculous results were nothing new to American newspaper readers. But in the late 1830s, tomato pills took over the market. This was especially surprising as Americans at the time had not considered tomatoes for their epicurean qualities, much less for their medicinal properties.

Botanically speaking, tomatoes are a fruit. Yet tomatoes are culinarily treated as a vegetable. In fact, pound for pound, they are the second most popular vegetable in the U.S. today, after potatoes. But 200 years ago, tomatoes were sooner found in a flowerpot than on a dinner plate.

“People had very different ideas about the right color of food, and red wasn’t one of them,” says Andrew F. Smith, food historian and author of The Tomato in America: Early History, Culture and Cookery. The daring red tomato was likely first introduced to North America by Spanish colonists in the 17th century. By the 19th century, some intrepid gardeners grew ornamental tomatoes because they thought they looked interesting. But few thought to actually eat them.

That attitude began to shift in 1834, when Dr. John Cook Bennett, a physician and amateur botanist, made a provocative announcement in the press: Tomatoes had medicinal properties. While there’s no evidence that Bennett conducted scientific research himself, he was a great promoter of other people’s work (though he often neglected to credit them), and he’d visited European hospitals and colleges where doctors recommended tomatoes to patients. He claimed that eating tomatoes prevented cholera and treated diarrhea, headaches, and dyspepsia.

Other vegetables had been similarly lauded with medical promise before. Sarsaparilla, mustard, dandelion, and rhubarb had all been deemed as curatives at one time or another. But Bennett insisted that tomatoes were a true wonder fruit, and he urged Americans to eat them often and in great quantities. He predicted that soon some pioneering person would figure out how to extract these miraculous properties from the plant and put them to medical use. By 1838, both Archibald Miles and Guy R. Phelps had claimed to have done just that.

Tomato pills proved to be big business. Miles had a network of agents and retailers that stretched from the Gulf Coast to the Canadian border. And he did not take kindly to upstart competitors. That year, a Miles-approved editorial in the New York Journal of Commerce claimed that Phelps was a “quack” and a “charlatan.”

Phelps countered by publishing a letter stating that Miles had “about as much claim to the title of doctor as my horse, and no more.” Phelps further insisted that Miles had essentially stolen his tomato pill formula. Endorsements ensued claiming that Miles’ pills were the “original” and that all other tomato pills were frauds. Miles eventually published an article arguing that the low price of Phelps’ pills was evidence that no tomatoes were even used to make them. Phelps called Miles “unjust and unmanly.” And on and on it went, playing out in the press for two years much to the delight of readers and newspaper editors, who seemed happy to publish credulous articles about tomatoes’ healing powers in exchange for tomato pill ad revenue.

Through all the claims and counterclaims, one truth did emerge: Neither Miles’ nor Phelps’ pills actually contained tomatoes. “Tomato pills were a joke,” says Andrew F. Smith. Of the tomato pills that were analyzed, none included a trace of the plant. It seems that the men’s main concern was less the health of their clients and more the health of their bank accounts.

But the tomato pills were effective in a couple unlikely ways. “There was a huge placebo effect,” Smith says. “Psychology plays such an important part if you think taking pills will help you with a specific ailment.”

The tomato pills were also mostly innocuous (they were essentially laxatives), which is more than can be said for other treatments at the time. Indigestion and other common ailments were often attributed to impure blood, and Miles and Phelps promised their pill could purify patients’ blood. But, in fact, most of these afflictions were likely caused by ingesting a potent slurry of polluted water and eating a diet high in salt, fat, and starch, and low in fruits and vegetables. At the very least, the tomato pill craze gave physicians something harmless to offer patients instead of mercury pills.

The battle over tomato pills ended abruptly in late 1839. It’s not clear exactly what transpired, but Phelps and Miles either came to an agreement or simply realized that it wasn’t in their financial interests to continue the war. Though tomato pills continued to be sold, Phelps ended his national advertising campaign in the spring and Miles in the summer. Miles went on to own a healthy tract of real estate in Ohio, though he continued to self-describe as a physician. Phelps founded a successful life insurance company in Connecticut and sold his tomato pills through the early 1850s.

With fewer ads circulating and some physicians publicly denouncing tomato pills, the buzz abated and sales dwindled. And yet, tomato pills had piqued Americans’ interest in the scarlet fruit. Even as the tomato pill craze fizzled, Americans continued to gobble up tomatoes at breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Tomatoes were served as main courses and side dishes, and with eggs, meat, and fish. There were savory tomato pies and sweet tomato tarts. Tomatoes were made into soups, jams, jellies, and ketchup. One journalist wrote in 1842 that he liked his tomatoes “fried in butter, and in lard, broiled and basted with butter, stewed with and without bread, with cream and butter.” A writer for the London Observer described the many tomato-centric meals he consumed while staying at a Wisconsin hotel in 1841: “At breakfast we had five or six plates of the scarlet fruit pompously paraded and eagerly devoured … At dinner, tomatoes encore, in pies and patties, mashed in side dishes, and dried in the sun like figs; at tea, tomato conserves, and preserved in maple sugar … ”

Cookbooks, magazines, and seed catalogues all picked up on the trend, praising tomatoes’ delicious, healthful, and fashionable qualities. “Within 10 years, tomatoes went from relatively little consumption to the queen of the vegetable market,” says Smith. By the early 1850s, millions of bushels of tomatoes were grown in New England alone. Tomato pills may have been a sham, but America’s love of tomatoes was the real deal.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook