In the 1800s, Valentine’s Meant a Bottle of Meat Juice

An act of love in the form of a medicinal tonic.

In Richmond, Virginia, a museum simply known as The Valentine tells the story of the city’s 400-year past. Set in a beautiful neoclassical building that dates to 1812, it was founded on the fortune one man made from his meat juice—which is exactly what it sounds like.

Before it became a museum, The Valentine was the home of dry goods merchant Mann S. Valentine II. In the fall of 1870, Valentine’s wife Anne Maria fell ill, apparently suffering from a “severe and protracted derangement of the organs of digestion,” as Valentine later wrote. Doctors had given up hope of curing her, and Valentine himself had been holed up in their basement for weeks.

But when Valentine emerged from the basement, he brought with him a potential cure that he’d cooked up. Knowing that Anne Maria couldn’t stomach solid food, but that she was in desperate need of nutrients, Valentine had concocted a tonic from beef juice and egg whites. The tonic was more effective than beef broth, he reasoned, because boiling meat for broth alters its proteins and leaves it “impaired in value.” By gently cooking the beef at a low temperature and then pressure-cooking it, he extracted juice from the meat that retained more of its nutritional value and “was acceptable to the most irritable stomach,” he wrote.

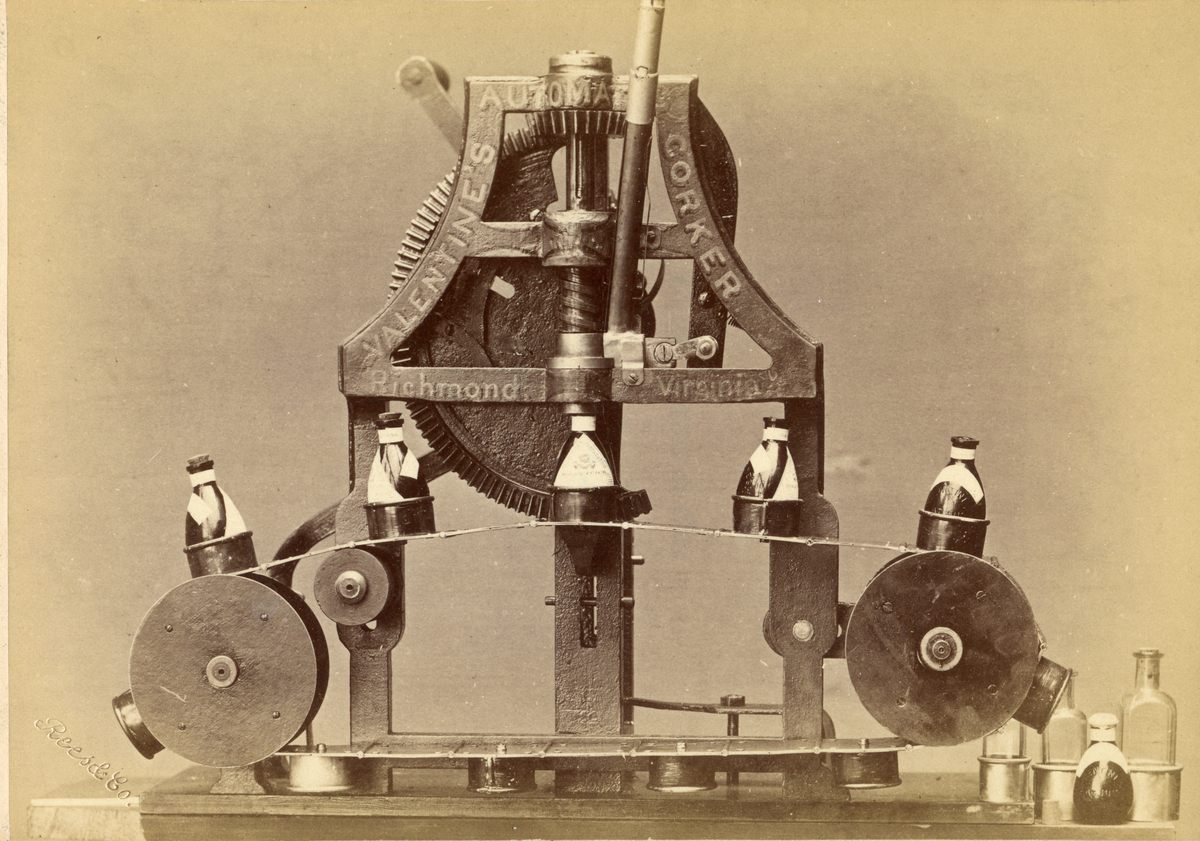

Valentine administered his tonic to Anne Maria, and in the following days, watched as she began to recover. Thrilled with his success, Valentine returned to his basement. He made more meat juice, sent samples off to doctors, and started to bottle and sell the tonic out of his home. Valentine’s Meat Juice company was born.

“I have been using your ‘Meat Juice’ on different cases in this hospital,” one New York Surgeon wrote to Valentine. “It has more than answered my expectations. I find that patients improve rapidly in appetite and strength under its administration.”

By 1874 Valentine had published a booklet filled with similar testimonials from doctors, who swore to its efficacy in curing everything from nausea to dysentery and cholera. Several doctors described administering Valentine’s Meat Juice to patients who refused any other form of nourishment, liquid or solid, and witnessing signs of recovery.

“One of my patients, seriously ill with typhoid fever, was nourished exclusively by it for two weeks, and daily increased in strength from its use, until firmly convalescent,” wrote one Virginia physician.

“I have found that this preparation stimulates the stomach when enfeebled from almost any cause, not only in dyspepsia and chronic gastritis, but in seasickness, the sickness of pregnancy, and such kindred complications,” another physician wrote. He claimed that he used the tonic by enema, to achieve better absorption, and found that it “exhibits its nutrient qualities in a remarkable degree.”

Another doctor eagerly suggested that Valentine’s Meat Juice be used as a substitute for meals when necessary. “In the hurry of business … many young men are debarred from taking their meals at regular hours, and to remove a sense of hunger or exhaustion, they are led to the use, or abuse, of alcoholic stimulation.” Taking a dram of meat juice instead of whiskey, he wrote, would be far more nutritious and avoid “any of the pernicious effects of the latter.”

By the late 1870s, Valentine’s Meat Juice had become one of the most popular and highly available patent medicines around the world. It was a top-selling product in American pharmacies and a fixture in many household medicine cabinets.

“The Meat Juice was incredibly popular the first decade or so that it came out,” says Lauren Gleason, a historian at the Stabler-Leadbeater Apothecary Museum in Alexandria, Virginia. “It was one of many pre-manufactured products that you could have bought at your average pharmacy in the late-19th century.”

The Apothecary Museum is the site of an original apothecary, or pharmacy, where Valentine’s Meat Juice was sold. Visitors often notice a small box in the museum’s collection that carries the Valentine’s Meat Juice label. “[The name] gets a good reaction out of visitors, which is fun,” Gleason says. “They’re like, ‘Ew, what’s that? That’s so gross.’”

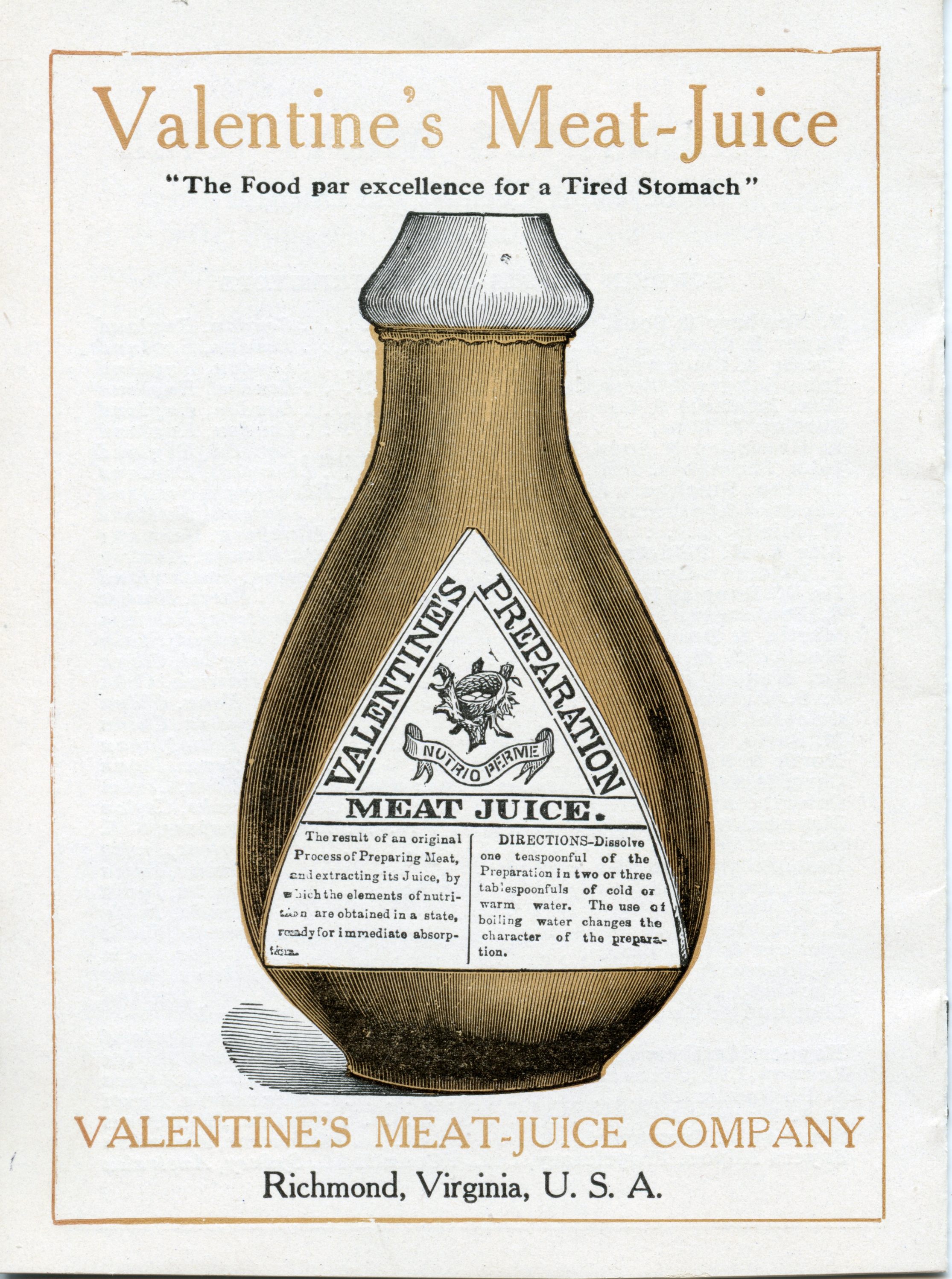

The preparation of Valentine’s Meat Juice, however, sounds almost savory. “Beef was pressure-cooked and strained to remove its juice, which was then boiled down into a concentrated liquid that was mixed with egg whites, later glycerin,” explains Meg Hughes, director of collections and chief curator at The Valentine. Patients were instructed to take one teaspoon of the protein-rich tonic diluted with two or three tablespoons of water (cold or lukewarm, but not hot). Many people also mixed it into soup or gruel, or if they had especially tender stomachs, into crushed ice.

Valentine’s Meat Juice was sold in a tiny brown bottle with a distinctive pear shape. After it achieved commercial success, other companies came out with their own meat-juice knockoffs. To foil copycats, Valentine trademarked the design of his bottle and his logo, which, for unknown reasons, featured a bird’s nest. He also successfully sued a London company called the Valentine Extract Company of London, which manufactured “meat globules” (similar to bouillon cubes), over its name.

Valentine was also a savvy marketer. He showed up with his meat juice at the International Exposition in Philadelphia, in 1876, determined to get greater visibility for his product. Two years later, he took it all the way to Europe for the Paris Exposition, where Meat Juice made a splash on the world stage.

Back in the United States, Valentine’s Meat Juice saw another boost in popularity in 1881, after the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal reported that President James A. Garfield took two teaspoons of it with his midday meal while recovering from an assassination attempt. However, Garfield ultimately died from complications arising from the gunshot wound, more than two months after it had been inflicted.

As for Valentine’s wife, Anne Maria, she lived for two more years after Valentine first revived her with his beef tonic. So did it actually play a role in her recovery that time?

“Of course we can never know if her husband’s tonic was actually effective, but I have to think that the dose of iron Anne Maria ingested in the meat juice could have been beneficial,” says Hughes.

The 1800s, when Valentine’s Meat Juice came along, was a sketchy time for medicine. There was nothing to stop patent medicine makers like Valentine from making misleading or even false claims about their products. Medical “quackery” was alive and well, and apothecaries often stocked drugs that were at best ineffective and at worst, downright dangerous. A patent medicine known as Fulton’s Renal Compound, for example, that claimed to treat kidney disease probably killed more patients than it cured. The 1906 Food & Drug Act, which was the first federal regulation of medicine in the U.S., cracked down on misinformation from the patent medicine industry. Among other things, it required manufacturers to list ingredients on their labels.

Gleason says there was probably nothing nefarious about how Valentine made or marketed his meat juice (and it may even have had mild health benefits). “When the product comes out, it was pre-Food & Drug Act, so there are no regulations that he’s having to adhere to,” she says. “He’s not having to say what was in his product. But it seems that it wasn’t anything terrible. You’d just squeeze a piece of meat, collect the stuff. Cook it.”

Sometime after 1906, however, the company rebranded its product as a flavoring for cooking, rather than a health tonic, and Hughes suspects the Food & Drug Act was a factor. By then, Valentine had passed away. His other legacy, The Valentine museum, opened in 1898 and featured art and curios Valentine had collected over the years. Valentine’s Meat Juice remained within his family until it closed in 1986, by which time the product was more commonly found in kitchen pantries than medicine cabinets.

While Valentine’s Meat Juice evokes an unfamiliar era, it isn’t entirely forgotten. As Hughes notes, there are still plenty of Richmonders who remember seeing it in the grocery store.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook