On Antarctica’s Vega Island, a Grinning Skull Is the Face of Climate Change

Satellite imagery recently captured a dramatic view of shrinking glaciers and snow cover on the remote island.

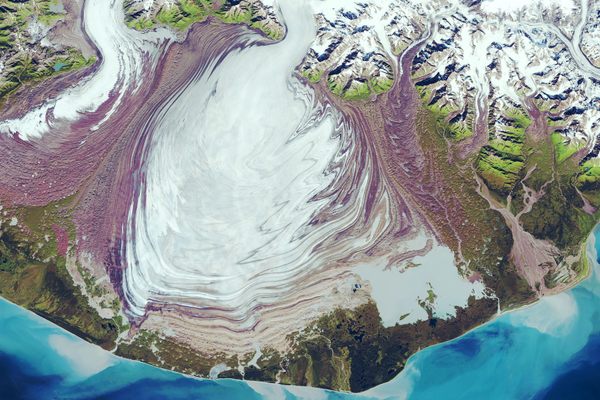

Against a background of bare rock, framed by the deep blue of the Southern Ocean, the profile of a grinning skull of snow and ice is likely the first thing you noticed about the image above. But there’s more to the story of this satellite shot, taken in February 2023, of Antarctica’s Vega Island—we’re looking not just at a case of pareidolia, but at the literal face of climate change.

We humans evolved a quirk in perception that makes us predisposed to seeing patterns that aren’t there, particularly faces in inanimate objects, from a “heathen maiden” trapped in Slovenian rock to Jesus appearing on cheese toast. (People have also seen the likeness of everyone from Elvis Presley to Donkey Kong at Japan’s Chichibu Chinsekikan, or Hall of Curious Rocks.) The phenomenon, known as pareidolia, has been observed in only one other species: rhesus monkeys, which, like humans, are highly social animals that appear to study faces for cues. However, there are suggestions that some of our closest evolutionary kin, such as Homo heidelbergensis and even earlier australopiths, experienced pareidolia up to three million years ago. Many evolutionary biologists suspect the phenomenon may be linked to the survival benefit of noticing subtle patterns in the environment—for example, it’s helpful to spot the face of a predator watching you from its hiding place in the long grass before it makes a move.

Now, our tendency to see faces where none exist may serve to remind us of a different kind of threat in our environment: the rapid and extreme changes in temperature occurring in polar regions.

Vega Island, less than 20 miles long and formed by a series of ancient volcanic eruptions, is one of a cluster of islands along the Antarctic Peninsula, the finger of land that snakes north toward Chile. Vega’s dark volcanic rock provides particularly stark contrast for its shrinking glaciers and disappearing snow cover. The island’s “eye” is actually a nunatak—an isolated peak surrounded by snow or ice—poking up from the Bahía del Diablo glacier, and has been visible for decades. The distinctive skull face itself, including the gaping mouth, has only emerged in the 21st century, due to climate change-induced melt.

In February, by the end of an unusually warm austral summer, the eastern edge of the island was free of snow and ice and the western area had lost nearly three-quarters of its typical snow cover. The entire Antarctic Peninsula is warming at a rate about five times faster than the global average, and observers noted that, this year, several areas had up to 20 extra melting days during the summer period of November through February.

The most recent summer stats are part of a growing trend that visitors to Vega have also noticed. Carnegie Museum of Natural History paleontologist Matt Lamanna, who has conducted fieldwork on Vega over multiple summer seasons, noted that his last visit, in 2016, coincided with the highest temperatures his team had ever experienced there, reaching about 55 degrees Fahrenheit. Vega is actually one of the best places in the extreme Southern Hemisphere to fossil hunt; Lamanna and colleagues with the Antarctic Peninsula Paleontology Project have found a number of significant Cretaceous fossils on the island, including remains of birds, non-avian dinosaurs, marine reptiles, fishes, invertebrates, and plants.

Ever the realist, Lamanna laments the shrinking glaciers but adds: “in a pathetic little silver lining, [it’s] exposing new fossil-bearing rocks for us paleontologists in the process.”

The skull face of Vega Island might also be seen in a more positive light. The smaller island that its grinning mouth seems to be about to chomp is Devil Island—suggesting to our brains, always looking for patterns in the world around us, that perhaps it’s not too late to take a bite out of the fiendish problem of climate change.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook