The Wild and Wonderful Whorls of Brash Ice

Wandering currents and spring thaws make sea ice in East Greenland look like curls of smoke.

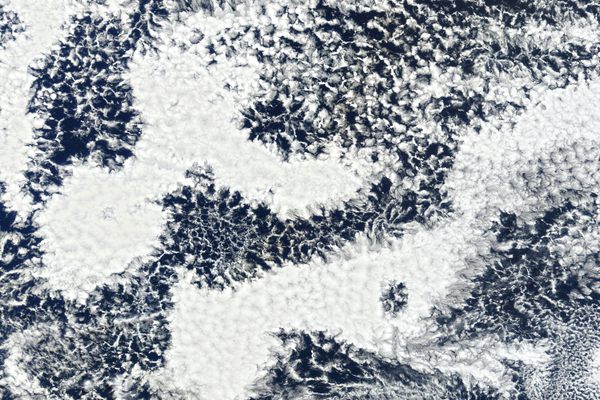

Ice is full of surprises, and we’re not talking about that slick patch you don’t notice until it’s too late. Water’s solid state can take some wild forms. There is delicate, rare, short-lived hair ice, which is sometimes mistaken for wads of wet toilet paper. The frozen Frisbees known as pancake ice are much more common, particularly in polar regions and the Great Lakes, but they’re not actually as flat as a, well, you know. Each thin piece has a raised edge of slush that builds up as it bumps into its neighbors.

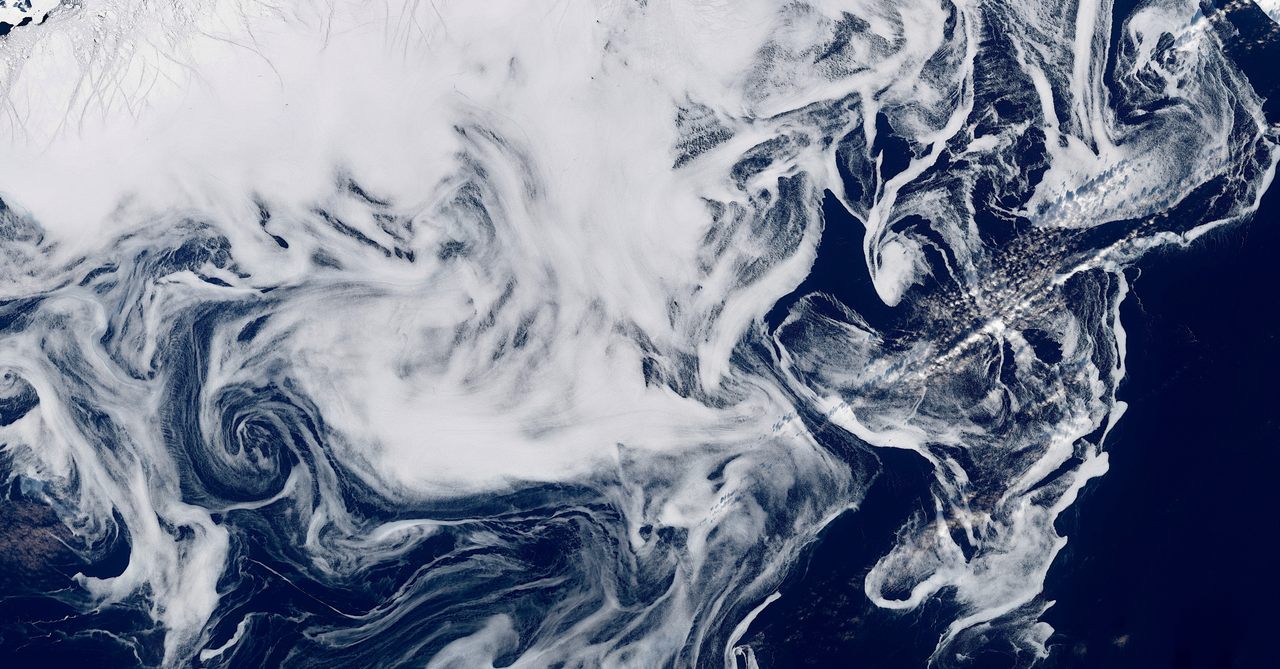

During spring in the Northern Hemisphere, drifting sea ice along a particular stretch of East Greenland takes on an enchanting form, but it is best seen from overhead. Far overhead. The European Union’s Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellite, which orbits Earth at an altitude of nearly 500 miles, captured the image above of ghostly whorls and curls of sea ice that resemble drifting smoke against the cobalt backdrop of the North Atlantic Ocean.

The patterns, many of them miles long, are actually made up of countless tiny fragments of brash ice, small pieces of drifting sea ice that result from bigger chunks colliding or collapsing as they start to melt. The brash ice swirls occur each spring in the waters south of the Fram Strait. This roughly 400-mile-wide stretch of water between Greenland and Norway’s Svalbard is known as the gateway to the Arctic because it plays a crucial role in global ocean circulation. It’s the only deep water connection between the Arctic Ocean and the rest of the world. (The Pacific-Arctic gateway, the Bering Strait, is much more shallow and also significantly narrower.)

Near Svalbard, the West Spitsbergen Current pulls warmer Atlantic water north while, closer to Greenland, another current serves as a sea ice super highway, transporting it south from the Arctic. As you might imagine, moving massive amounts of water and ice through this relatively narrow strait makes for some rough seas. The south-flowing East Greenland Current is particularly unstable, and tends to wander, often creating vortices as it changes course. All that south-flowing brash ice, floating lightly on the surface like foam, goes on a wild ride, pulled this way and that by the fickle current.

Eventually, about 900 miles south of the Fram Strait, the drifting sea ice gets pinched between Greenland and Iceland in the Denmark Strait (also known as the Greenland Strait), where the top image was taken.

The delicate tendrils and marbled patterns captured by satellites each year are the ice’s last hurrah before it all melts into the North Atlantic. While we might appreciate the aesthetics of the images, they are also important to scientists tracking the extent of annual sea ice and other indicators of intensifying climate change. The swirling brash ice is also a visible sign of ocean circulation, a global exchange of nutrients, carbon, and heat cycling around our planet that’s usually invisible to the naked eye.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook