Being an Ottoman Janissary Meant War, Mutiny, and Baklava

To overthrow the sultan, janissaries first threw over their cooking pots.

In the spring of 1806, Istanbul was in uproar. Sultan Selim III wanted to modernize his military, with new uniforms and European-style fighting techniques. But other sultans had tried before, and failed. Reform required getting rid of the janissaries, a centuries-old class of soldiers. Unfortunately for Selim, the janissaries would soon give their usual sign of rebellion: publicly overturning their giant cooking pots. For the corps, whose traditions revolved around food, this amounted to a declaration of mutiny.

For centuries, the janissaries had been one of the most feared fighting forces in Europe. Trained as infantry from youth, it was the janissaries who breached the walls of Constantinople in 1453 and devastated Hungarian knights at the Battle of Mohacs in 1526. “They were a modern army, long before Europe got its act together,” says Virginia H. Aksan, professor emeritus of history at McMaster University. “Europe was still riding around with great, big, heavy horses and knights.”

Decked out in glorious uniforms and alerting enemies to their presence with thunderous drums, they were “both a cause of terror and a source of admiration for the West,” writes historian Gilles Veinstein. Under a system likely established by Sultan Murad I in the 14th century, Ottoman authorities took boys from Christian families across the Ottoman Empire as a sort of tax. Called a “gathering,” or devşirme, the boys underwent stringent training as archers and later as musketeers, along with conversion to Islam.

Accounts abound of Christian families, especially in the Balkans, doing all they could to keep their sons from being taken away. Yet if they became janissaries, the boys were freed and considered the “sons of the sultan,” Aksan says. The best of the best rose to positions of influence and power in the Ottoman bureaucracy. However, Veinstein notes, janissaries could be “a danger for the Ottoman rulers.” Should a sultan cross them, janissaries would rise in revolt.

Their signal to mutiny was overturning their massive cooking pots, or kazan. Tipping over a huge cauldron might seem like a goofy way to start a rebellion. But for janissaries, both the kazan and food in general were potent symbols. Accepting the sultan’s food was a sign of loyalty and dedication to him, writes Ottoman historian Amy Singer, and eating from the kazan helped “create group solidarity.”

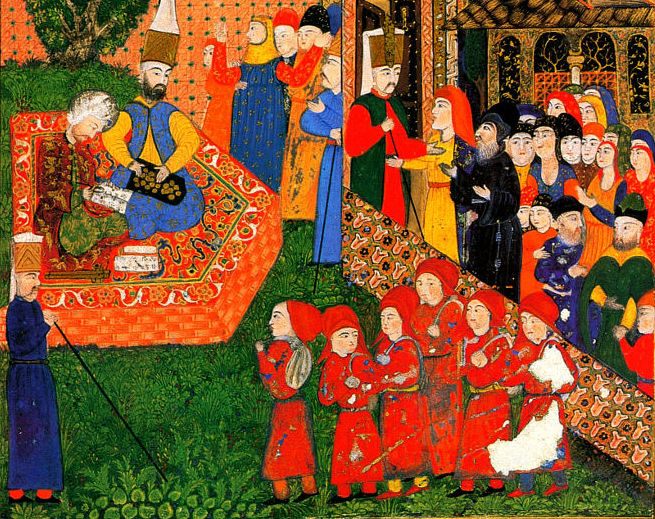

The kazan also had a spiritual meaning. One legend held that Haci Bektas Veli, the founder of Bektashi Sufism, founded the janissaries and “served them soup from the ‘holy cauldron,’” writes Singer. Janissaries were often members of the Bektashi order, and to the Bektashi, “the hearth and home were sacred.” Used for Bektashi ceremonies, the cauldrons took on a similar significance to the janissaries. Contemporary illustrations of janissaries show lavishly dressed soldiers proudly parading along with their kazan.

Every three months, when janissaries got their salaries, they paraded to Topkapi Palace, where they also received soup, pilaf, and saffron pudding. Each year during Ramadan, janissaries marched to the palace kitchens in the “Baklava Procession” to receive a massive amount of sweet treats. Well in advance of cauldron-flipping, any hesitance to receive food from the sultan was a warning that an orta, or regiment, was on the verge of mutiny.

Janissaries adopted cook-like titles as well. Their sergeants, the highest-ranking member of each corps, was the çorbacı, or the “soup cook.” According to Aksan, the janissary corps was referred to as the ocak, which meant the hearth. “That comes from the notion that they were the sultan’s sons,” she says. “You have the household, and janissaries are an essential part of that.” Also gathered around the hearth, writes Singer, were “lower-ranking officers” with titles such as aşcis, or cook, and the kara kulluckçus, or scullion.

In the early-16th century, janissaries numbered around 20,000, and that number would steadily increase. But the janissaries slowly lost power as a fighting force. Devşirme was abolished in 1638, and the ban on marriage faded as well. The sons of janissaries were allowed into the ranks, and soon free citizens vied to join. It wasn’t long before janissaries were running businesses while still expecting pay from the sultan. As Aksan notes in the Oxford Companion to Military History, by the end of the 17th century, their numbers had swelled to nearly 80,000, and in 1800, the rolls of the janissaries contained nearly 400,000 names. At that point the title was almost meaningless, and only around 10 percent “could be called upon to defend the empire.”

Yet woe betide the sultans who tried to replace the janissaries, or, Aksan notes, to debase the currency. Janissaries never appreciated either attempt, and the mutinies could be devastating. Despite their vaunted loyalty, janissaries deposed several sultans, starting with the murder of the teenage Osman II in 1622. He planned to dismantle the janissaries and, expecting defiance, he closed the coffee shops where they gathered. Rising up in revolt, janissaries killed him. Selim III was forced off his throne by the janissaries, and later murdered. In the end, janissaries became like the Praetorian Guard of ancient Rome. Mutiny was their privilege, says Aksan, and sultans had to appease them.

Aksan calls the janissaries “the central icons of the Ottoman’s heyday.” But as they lost battles across Europe and became more unruly at home, both the sultan and the public had enough. Sultan Mahmud II, seeking to modernize his military forces, had a brutal solution to disbanding the janissaries in 1826. The janissaries overturned their cauldrons at dawn on June 15, but the sultan had planned ahead. He destroyed their barracks with artillery and had them “mowed them down in the streets of Istanbul,” says Aksan. With survivors exiled and executed, it was an ignominious end for the sons of the sultan.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook