The Founder of America’s Earliest Lesbian Bar Was Deported for Obscenity

Eve Adams was eventually murdered at Auschwitz.

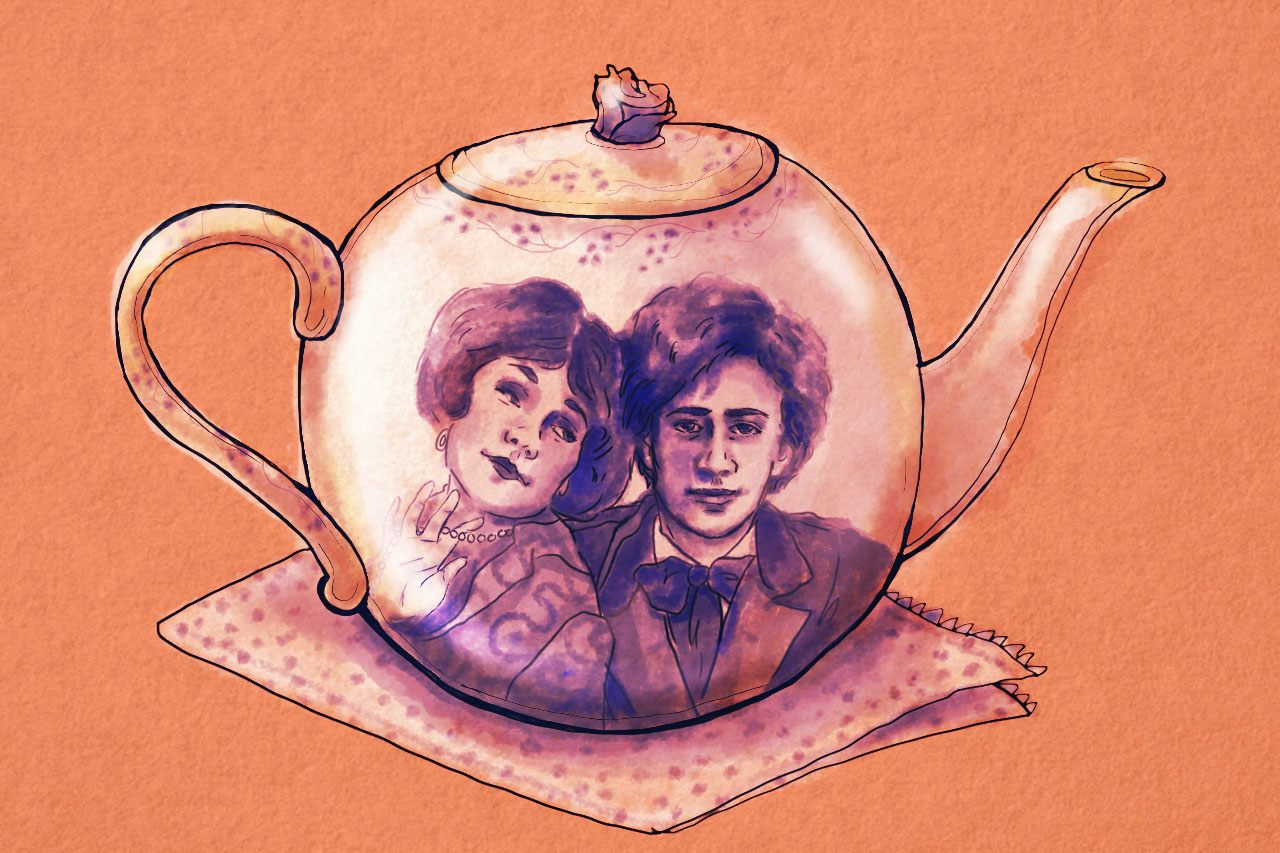

It took Officer Margaret Leonard three tries to get her hands on Eve Adams’ book of lesbian short stories. We don’t know what, exactly, the New York Police Department officer experienced when she first slunk undercover into Eve Adams’ Tearoom at 129 MacDougal Street. But it’s easy to imagine a group of artists gathered under gleaming electric lights on a hot June night, reciting poetry or discussing the latest performances in the Provincetown Playhouse next door. Leonard’s mission was simple: to “catch” Adams “in the act” of lesbianism, either by eliciting a romantic move or by finding evidence of obscenity. Lesbian Love, a book of short stories Adams had self-published and distributed among friends, was just the evidence Leonard needed to have the tearoom proprietor arrested.

Established in 1925, Eve Adams’ Tearoom, also known as Eve’s Hangout, was one of the hottest nightlife spots in New York City’s flapper-era West Village. While the establishment is often remembered as a speakeasy, Barbara Kahn, who has done extensive research on Adams and wrote three plays about her life, says the lack of police allegations of alcohol possession suggest that it really did serve tea. But more was on tap at Eve’s Hangout than just after-theater beverages. A magnet for the The Village’s diversity, the tearoom was an open space for Jewish and immigrant intellectuals, who weren’t always welcome in the xenophobic cultural life of the time. Above all, it was a safe space for women, who frequently could not venture into restaurants without a male guardian, and particularly for lesbians. The tearoom’s ethos was summed up in a sign that greeted visitors: “Men are admitted but not welcome.”

“It was probably a joke,” says Kahn of the sign. After all, male cultural figures frequented the tea room. Still, Eve’s Hangout was undoubtedly a safe space for queer women, and hosted after-hours, locked-doors meetings, where women-loving women could share their experiences without fear of censorship or discrimination. Ironic or not, the sign reflects Eve’s Hangout’s historical significance. Despite the tea room’s popularity, the story of its proprietor was lost to the public for decades. But amid current efforts to retrace LGBTQ cultural history, researchers such as Barbara Kahn are restoring Adam’s tearoom to its place of honor as one of the first lesbian establishments in the United States.

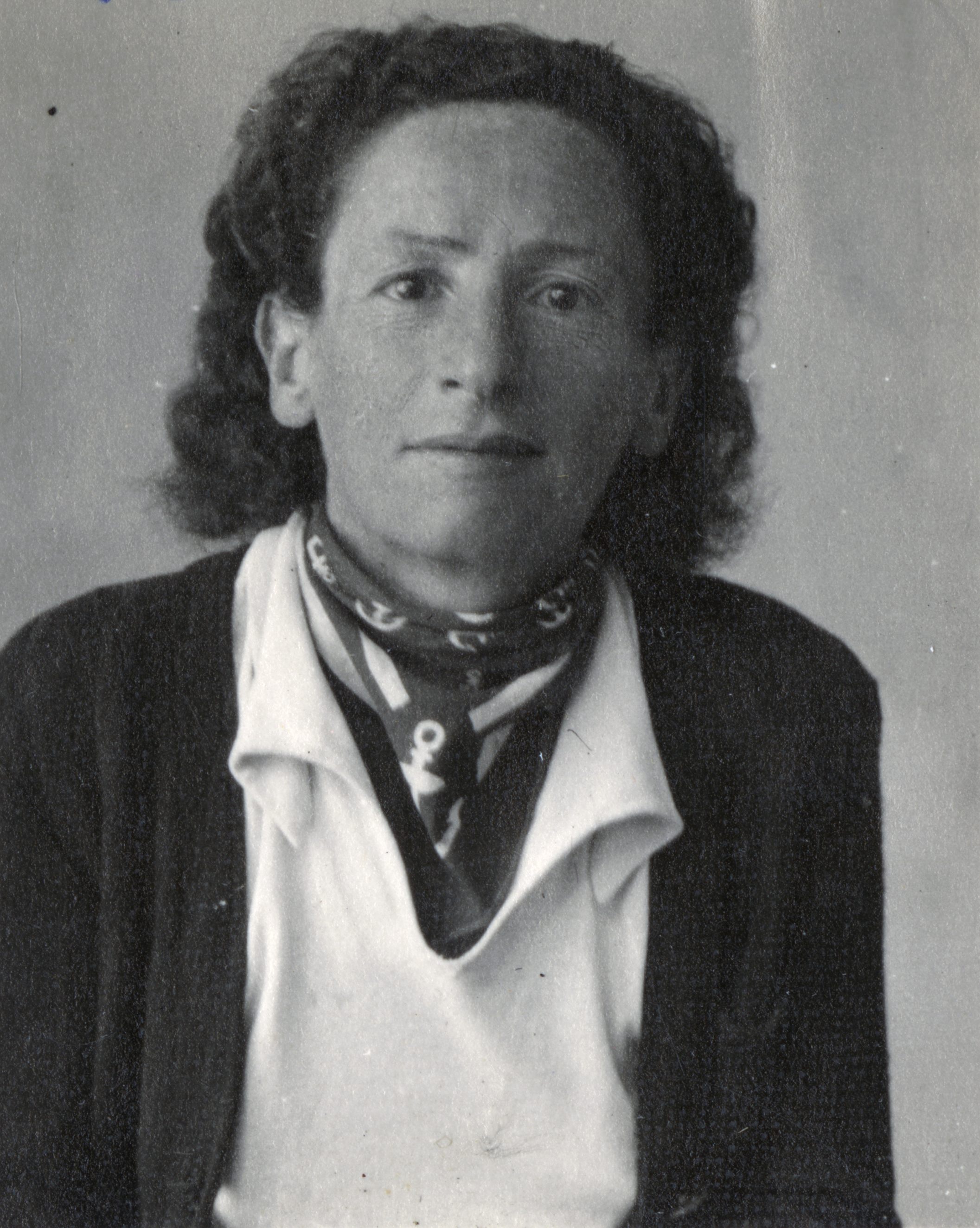

Tea and poetry kept the Hangout going, but Eve Adams was its soul. Described by commentators as “the queen of the third sex” for her masculine appearance (language commonly used at the time), Adams was popular among the bohemian literary figures of 1920s New York. Born Chawa Czlotcheber (sometimes spelled Zlocsewer, Zlotchever, or Kotchever) to a Jewish family in Mlawa, Poland, Adams immigrated to the United States as a young woman in 1912, and spent several years traveling before settling in Manhattan’s Washington Square. At some point, she Anglicized her first name to “Eve” and took “Adams” as her chosen last name. The name, writes George Chauncey in his history of gay New York culture, was “an androgynous pseudonym whose biblical origins her Protestant persecutors might well have found blasphemous.”

Adams was just one of many 1920s New York artists and writers who lived political and sexual lives that went against the mold. Eve counted many of these figures among her friends: author Henry Miller, whose work was frequently banned and to whom she loaned money when his wealthy mistress couldn’t front his bills; Anaïs Nin, whose crystal-sharp stories are full of lesbian tension; Emma Goldman, the New York labor activist whose practice of free love was as famous as her anarchism. While Adams, likely due to her sexuality and immigration status, lacks the fame of these companions, she and her tearoom were popular among this elite cultural crowd.

Like all women ahead of their time, Eve Adams also made enemies. Chief among them: Bobby Edwards. A writer for the Greenwich Village Quill, where he covered society life, Edwards didn’t like the increasing gay and immigrant presence in the village. “He was an all-purpose bigot,” says Kahn. He wasn’t the only one. “There were tour buses that would go down to the Village to see all these terrible places: all these bohemians, all these ‘perverts,’” Kahn says.

While Bobby Edwards covered events at Eve’s Hangout, he spared no kindness for Adams herself. “Eve’s Hangout,” he wrote in a June 1926 guide to Village clubs, “Where ladies prefer each other. Not very healthy for she-adolescents, nor comfortable for he-men.” This animosity is why, when police raided Eve’s Hangout in 1926, word on the cobblestoned Village Streets was that Edwards had something to do with it.

At the time, police raids targeting local speakeasies were common. In Adams’ case, however, the NYPD’s tactic was decidedly personal. After spotting the undercover cop at Eve’s Hangout, on June 11, 1926, Eve Adams finally asked Margaret Leonard to the theater. Later, Leonard alleged that Adams took her dancing, held her too close, and “had her hand on my bosom” in the cab. Worse, said Leonard, Adams had invited her up to her bedroom and ostensibly threw her onto a bed and, according to a police report, “attempted to commit the crime of conenlinguism.” At this point, Leonard left the scene and phoned the police station. She had slipped out with what seemed, to the morality police of New York City, a Sapphic smoking gun: a copy of Lesbian Love, a collection of short stories that Adams had printed in a small run. (Several copies of the book exist today, though they’re privately owned; Kahn says one went missing, possibly purloined, from the Yale library a couple years ago.)

Cops arrested Adams at her Hangout that night. She was charged with obscenity and disorderly conduct, and sent to a New York workhouse for six months. An uncle in Hartford offered to post $1,000 bail, but the City of New York wouldn’t take it. Instead, immigration and police authorities pursued “evidence” of Adams’ sexual orientation, including a letter from Adams’ neighbor, Jay Fitzpatrick, alleging she regularly brought young women to her apartment for sex. “I know personally of decent girls who have been corrupted by this woman,” Fitzgerald wrote.

In a twist of fate, Adams crossed paths with another notable woman in jail, Mae West. The famous writer had been sentenced to 10 days imprisonment for the alleged obscenity of her acclaimed Broadway play, Sex. While West dined with the wardens and was quickly released, Adams was deported to Poland in 1927. For Kahn, the reason for the difference in treatment was clear: The United States government had no sympathy for an immigrant, Jewish lesbian. “I love this country with my whole heart and soul, and I have made application for my final papers. I want to become a citizen,” Adams said in a deposition. “If I am deported, my life is ruined.”

As with many immigrants who fled persecution, the facts of Adams’ life sometimes fall out of focus. Look Adams up online, and you’ll find a dust storm of apocrypha about the era after her deportation. Some say Adams opened another tea room in Paris and studied at the Sorbonne. Some say she went to Spain in the 1930s to join the struggle against Franco or to report on the Spanish Civil War. Kahn, who has tracked down her deportation records and found mentions of her in the letters of Paris-based cultural figures, says there’s no evidence she ever went to Spain. Instead, it seems this story has origins in Adams’ family, some of whom said that she had left the U.S. voluntarily to fight fascism.

What we know for sure is that, by the early 1930s, Eve Adams had saved up enough money to move from Poland to Paris. At first, life in the romantic, lamplit city was as electric as it had been in 1920s New York. Adams remained part of a circle of bohemian artists, and made a living selling English literature to tourists and expats. She had sold avant garde literature from her New York tearoom, and in Paris—in homage to the censorship that had cost her a home in the United States—she specialized in the banned. In letters between her and Henry Miller, there are mentions of her selling his book Tropic of Cancer, and complaints from Adams that people couldn’t get enough of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. (D.H. Lawrence was a notable homophobe.)

But the antisemitism and homophobia that had already uprooted Adams found her again. In 1940, the Nazis marched into Paris. Like many Parisian Jews, Adams fled to southern France. She desperately sought help from friends and foreign governments, but with only an expired Polish passport and a discontinued American citizenship application, she had no luck. Some of her family members in Poland had already been displaced or murdered by Nazis.

Adams was in Nice when Nazi officer Alois Brunner assumed control of the territory in 1943. She was rounded up alongside hundreds of other Jews. Allied pressure was building; by August 1944, thousands of Allied soldiers would land on beaches in southern France. But by then, many of Nice’s Jewish residents had already been captured. After her deportation, Adams was held briefly at a transit camp in France before being sent onward. Like other immigrants and refugees to whom the United States denied residence, in 1943, just two years before the camp was liberated, Eve Adams, the beloved proprietor of one of the world’s first lesbian restaurants, was murdered at Auschwitz.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook