Hop Alley

A mural and a few historical markers commemorate Denver's once-thriving Chinatown, which was obliterated in a racist riot.

In the late 19th century, thousands of Chinese immigrants came to the United States to find work. Many found work building the railroads linking the populated east to the frontier west. Along the west coast, enclaves of Chinese immigrants established communities known as Chinatowns. With much of the railroad work being done in the nation’s interior, one might wonder why Denver, Colorado, the largest city of the Rockies, doesn’t have a Chinatown of its own. But the real question is why doesn’t Denver have a Chinatown anymore?

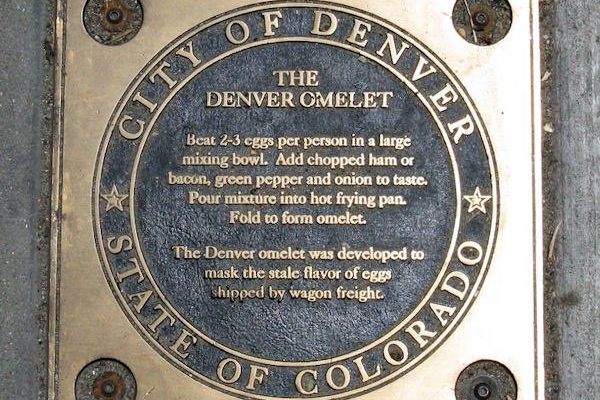

Denver’s Chinatown was born in 1869, when the first Chinese immigrant, Hong Lee, came to run a laundry business. He planted the seed for Denver’s new Chinatown, which ran mainly along Wazee Street. At its peak, it had a population of over 1,400, the largest in the Rocky Mountain region. It was nicknamed Hop Alley, a moniker that referenced the opium dens that could be found in several Chinatowns across America.

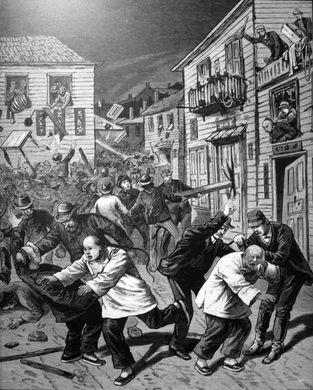

While the new Chinatown provided much-needed labor and markets for the growing city, many in the white majority of Denver grew hostile to their neighbors. Chinese immigrants were blamed for opium dens, sex work, and gambling—which were just as ubiquitous in white communities. These sentiments were by no means unique to Denver, but it was here that they culminated in one of the most destructive riots in American history.

On October 31, 1880, two Chinese men were confronted by drunk patrons of a pool bar. As the two men were leaving, one of the assailants assaulted them with a board in broad daylight. This escalated into a mob of about 3,000 men, who began ransacking the Denver Chinatown. One resident was killed, and the homes and businesses of nearly everyone in Hop Alley was destroyed.

Most of the Chinese left Denver and were not compensated in any way for their losses. Two years later, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred further Chinese immigration and prevented current residents from applying for citizenship. In 1940, the few remaining residents of Denver’s Chinatown were forced to leave when the district was razed for an urban renewal project.

The existence and destruction of Hop Alley is not well-known in Denver, and efforts to keep its memory alive have often fallen short. For decades, there was one sole plaque at the site of the old community, referring to the “Chinese Riot of 1880.” Obviously, this description was easily misread, and in 2022 the plaque was removed and replaced by three more historically accurate markers. Denver artist Nalye Lor was commissioned to paint a mural on the side of Denver Fire’s Station #4. The artwork features silhouetted railroad and laundry workers, as well as a railroad track. A long, unbroken noodle winds through the design—it’s a longevity noodle, said to symbolize a long life.

The Chinese text on the mural is a proverb that translates as “Be not afraid of going slowly. Be afraid only of standing still.” Hop Alley may be no more, but recognition of its existence paves the way for a deeper understanding of Denver’s history and how it can improve. While a few signs and a mural are small compared to what was here before, it is a step in the right direction. As Nalye Lor said at the outset of her creation, she hopes viewers “really take a minute to think about history and see what they can learn from it, but also what they can change to really make a difference today.”

Know Before You Go

The mural is located on Denver’s Fire Station #4, near Union Station. There is a historical marker nearby that tells the story of Look Young, who was murdered in the riot.

Two more historical markers can be found at 1620 Wazee St and 1520 16th St Mall, telling the history of Hop Alley and the riot that destroyed it.

Plan Your Trip

The Atlas Obscura Podcast is Back!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook