In the Footsteps of Ecuador’s ‘Mama Warrior’

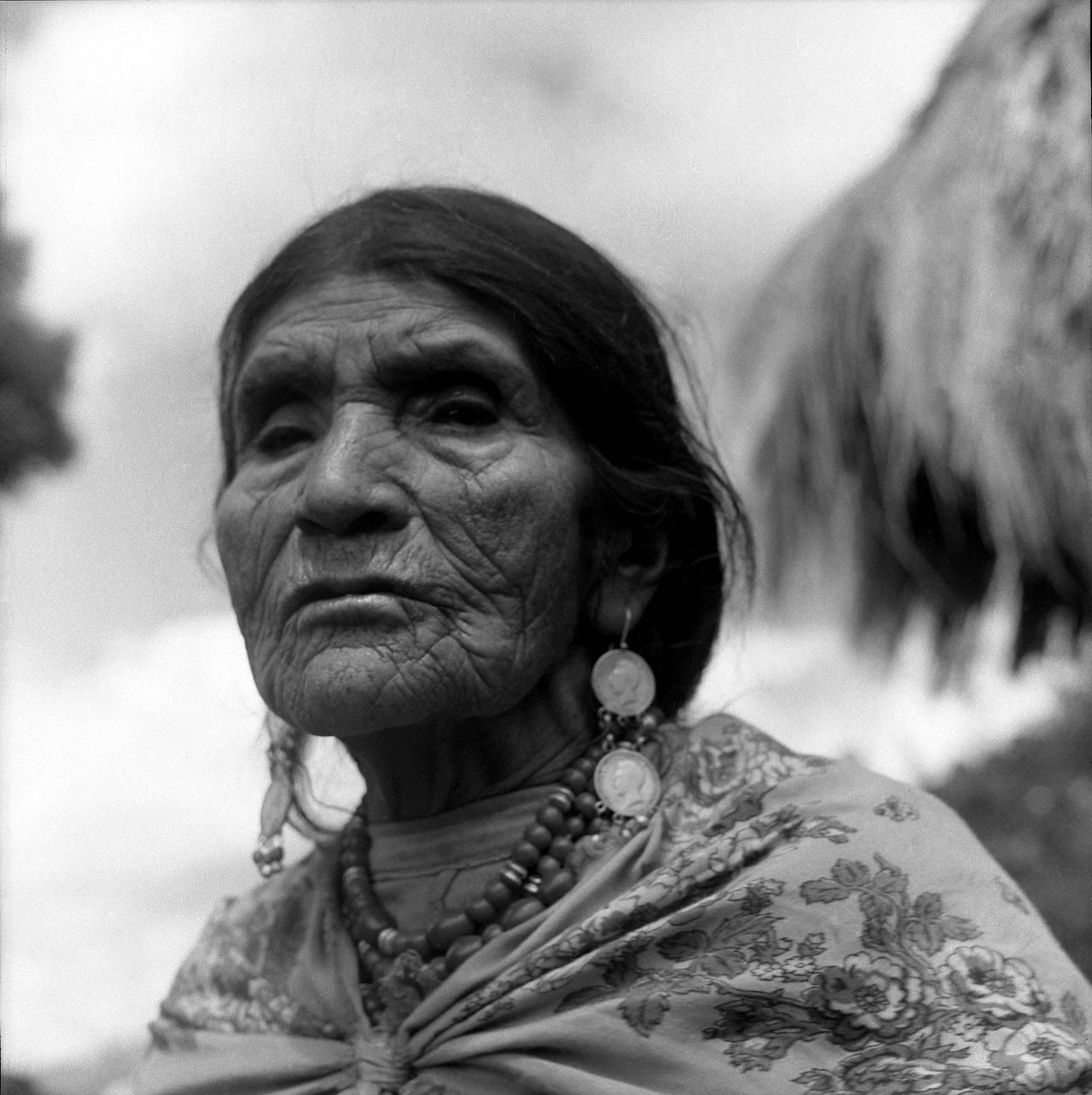

How the country’s Indigenous communities are keeping the memory of activist Dolores Cacuango alive.

At the turn of the 20th century, Indigenous Kichwa communities in the Andes Mountains of Ecuador existed under a cruel hacienda system. Most Kichwa people lived in small adobe huts and worked for landowners who often withheld pay, keeping them in debt, and violently punished or humiliated them for not obeying the rules. This is the scene that Dolores Cacuango was born into in 1881, and this is the scene that inspired her 30-year struggle for Indigenous rights.

Cacuango—or Mama Dolores as she is affectionately known today—has been called a fighter and a visionary. She organized rebellions in Indigenous communities, began clandestine schools in rural communities, fled from government persecution and co-founded the country’s first Indigenous organization. The hacienda system has been dismantled, but the Indigenous struggle for equality in Ecuador continues today and the national Indigenous confederation, CONAIE, is now considered one of the country’s strongest social movements. It has an earned reputation for mass protests and is credited with toppling three governments since 1990 for trying to pass oppressive austerity measures. Many say this fight began with Mama Dolores.

Over the years, Cacuango has been commemorated publicly in various ways. Ecuador’s famous painter Oswaldo Guayasimin included her portrait in his mural, Image of a Homeland, in Ecuador’s National Assembly; a wooden statue of her was erected in the town of Olmedo, where she was also buried; and her portrait was painted as a small mural in Cayambe. Yet she is barely mentioned in the country’s schools, which are focused more on the country’s colonizers and nation making than the acts of resistance against it. It falls instead to Indigenous communities across the country—as well as some academics—to pass Cacuango’s memory to the next generation.

“There are people who believe that today, everything [we have] has been thanks to the governments of the moment and their goodwill,” says Laura Tenemaza, vice president of the Indigenous Union of the Province of Cañar. That is not the case, she says. “The indigenous movement, and everything that we have today and the things that we have achieved is thanks to this [history].”

Cacuango was born in a hacienda owned by the Mercedarian friars, in the green and lush Andean foothills north of the capital Quito. Her parents were at the bottom of the hierarchical hacienda system, living in an adobe hut on a small piece of land called a huasipungo, and working for the landowners for free, writes the historian Raquel Rodas in her biography of Cacuango.

In her early teenage years, to avoid being forced into marriage by the friars, Cacuango fled the hacienda for Quito, where she worked for years as a housekeeper for a military general. It was here that she learned to speak Spanish through listening and repeating conversations around her. A few years later, she took this knowledge back to the hacienda, where she married Rafael Catucuamba. She bore nine children over the years, only one of whom survived the harsh conditions of poverty on their huasipungo.

Cacuango became known for being outspoken and continuously fought with the hacienda owners to pay Indigenous workers fairly, particularly the women who were often forced to work in the homes for free, and against the violence inflicted on them. She channeled that energy to work with the socialist party and later the communist party, who helped the Indigenous people organize unions in the 1920s.

In 1930, Cacuango organized the first Indigenous march to Quito to demand their rights from President Isidro Ayora himself. Some 1,000 Indigenous people walked to the capital—about 43 miles—and filled the central plaza, something urban Ecuadorians had never seen before.

Cacuango was then forced to leave her family temporarily and flee into the mountains to escape being caught by police who were searching for the organizers in their communities and burning down homes. Still, she continued to organize communities, and in 1944, she co-founded the Ecuadorian Federation of Indians, FEI, together with other leaders and the Communist Party, creating the first Indigenous organization in the country. She then created schools in rural areas, bringing literacy to Indigenous kids and adults.

But Cacuango’s schools were closed in 1963 under the dictatorship of general Ramón Castro Jijón, and in 1970 he passed agrarian reform that largely left Indigenous families worse off, with no tools or resources to work their newly assigned small parcels of land. This included Cacuango and her family.

Cacuango passed away the next year, laying on her bed of straw in her adobe hut, her revolution seemingly forgotten.

Mama Dolores was little remembered at the time of her death at the age of 89, but her fight was not in vain, says Vicenta Chuma, a Kichwa leader with the Indigenous Union in the province of Cañar.

In 1997, Chuma co-founded the Dolores Cacuango Training School for Women Leaders, just one of many ways Ecuador’s Indigenous organizations have tried to keep Mama Dolores’s memory alive and empower women. The school started with 60 women and within three years over 300 were enrolled in the leadership program. Though that school is now closed, similar leadership schools continue to spread Cacuango’s story.

“For us she is a symbol, she is an example. For the women of this time, Dolores was an eminence,” Chuma says. She taught her students about Cacuango’s personal life, her political fights, and her organizing, “so they can take her story, and can value our own struggle and show up for our own organizations today.”

Paola Montenegro, a social science teacher in Quito with a background in critical pedagogy, says Indigenous movements in Ecuador, particularly its women leaders, have largely been left out of history classes in the country’s schools. Since 2016, when the curriculum was last updated, you can find a photo of Cacuango and a small blurb about her life as an Indigenous woman leader in some history and social science textbooks. But they don’t show her as an important political actor who fought against a violent hacienda system, advanced Indigenous rights, and inspired years of organized resistance by later Indigenous movements. Instead, the national curriculum focuses on the Spanish conquest, a little bit of Inca history, then quickly moves on to study the Republic of Ecuador and past presidents, Montenegro says.

“It’s like we don’t recognize this part of history, we still have a very colonialist history,” says Montenegro. “Maybe they assume that people are going to have a political position on this. So generally the context that they put [the Indigenous movement] in has been very broad,” she added.

Mama Dolores’s fight isn’t in the past, Chuma says. In October 2019, Chuma was one of thousands who took to the streets in the 12-day protests, largely led by CONAIE, against the IMF austerity measures proposed by then-President Lenin Moreno. The protests only ceased after the president sat down to negotiate with Indigenous leaders and repealed the austerity measures. (Many of them have since been reinstated during the pandemic.)

“Our rights are being trampled everywhere,” says Chuma, naming poverty and lack of access to university education, healthcare, and jobs as some of their biggest struggles. “Of course, we need to keep fighting,” she says. Today, more than 50 years after her death, Cacuango’s name is chanted in marches, to enliven and encourage people to go on: “Dolores Cacuango! Mamá Guerrera! Por tu camino, compañera!” Dolores Cacuango! Mama Warrior! In your footsteps, friend!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook