How Women—and Their Hair—Transformed South Korea

Newly fashionable in the 1960s, wigs brought millions of dollars into the war-ravaged country.

Seoul in the summer of 1963 rumbled with change—literally. The Korean War had ended with an uneasy armistice in 1953 that cleaved the country in two, and the new military regime unveiled a grand plan of “national modernization,” which included repaving miles and miles of Seoul’s dilapidated roads. Clouds of dust shrouded the capital while the ring of sledgehammers pounding earth hung in the air.

Amid this cacophony, Kang Chae An was playing in the new alleyways of her working-class neighborhood, Ahyeon-Dong, when her mother called her home. Kang’s thick, black hair—“like a horse’s mane,” relatives complimented—stuck to her neck in the sweltering heat. Under the guise of providing some cooling relief, her mother announced it was time for Kang, who would soon start second grade, to get her first haircut. “I was not ready to cut my hair. The adults grabbed me and chopped it off,” Kang, now 68 years old, recalls. “I was so traumatized that I still remember that day very clearly.”

As in many places influenced by Confucian thought, Koreans traditionally saw hair as a precious gift from one’s parents. But the Kang family, like most Korean families at the time, were financially devastated by the war. “Growing up after the war, I always wondered why we were so poor. Everyone around us was poor too,” Kang says. Kang’s mother, who was a skilled seamstress, worked multiple jobs while her father was a mechanic, yet hunger remained a common experience. In the first decade of Kang’s life, Korea ranked among the poorest countries in the world with a per capita income of less than $100—and women’s hair had suddenly become a valuable commodity.

“My mom passed away, but I never asked her why she did that to me,” Kang says of that first, shocking haircut. But she had her suspicions. Kang overheard her mother tell the other women in the neighborhood that she used the money from selling her hair to buy rice, flour, and noodles. “I think we needed the money to feed the family, so I felt bad to ask her such a question.”

The following year, South Korea—where cutting hair had been considered taboo for centuries—was exporting 474 metric tons of human hair to supply the global wig industry, putting women at the center of South Korea’s transformation from a war-ravaged society into the modern, economic powerhouse it is today.

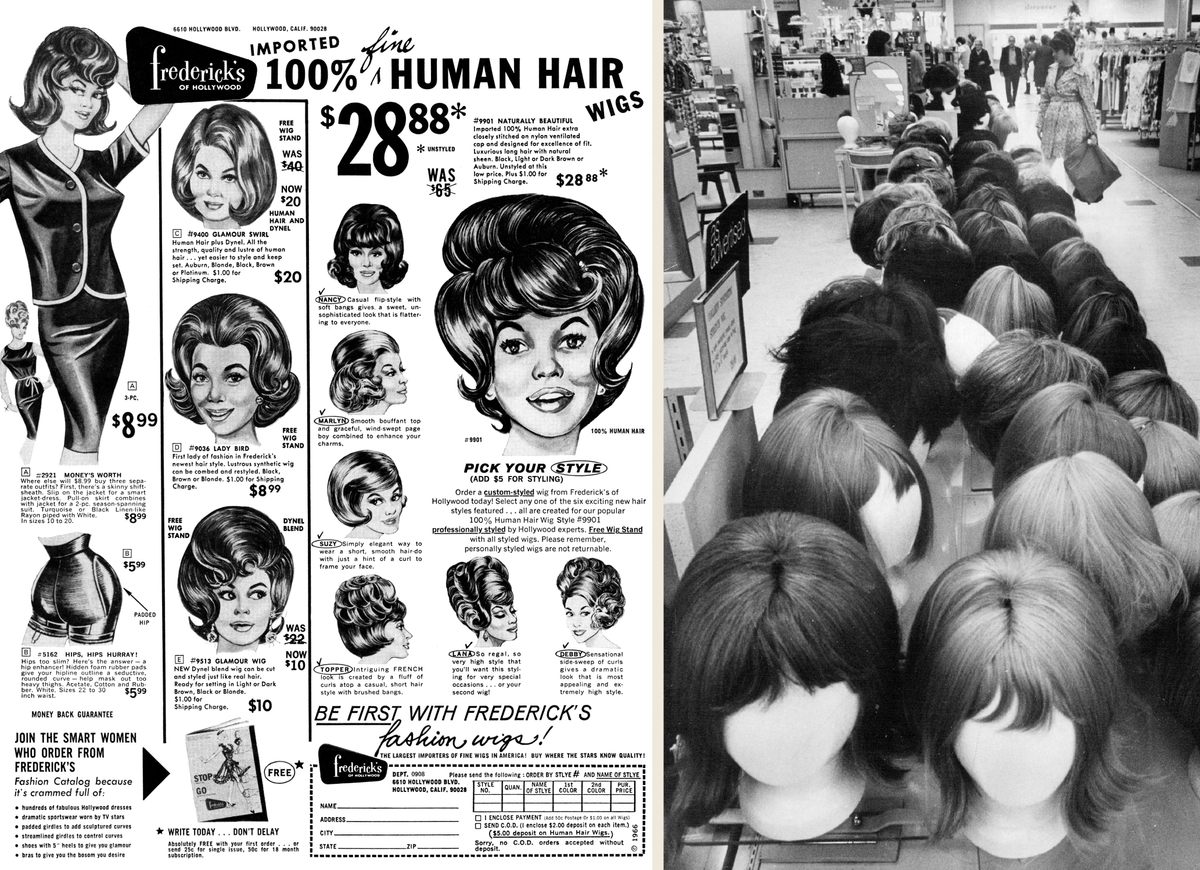

The global wig industry has its origins on the runways of Paris in 1958, says Jason Petrulis, an assistant professor of global history at The Education University of Hong Kong. From there, the trend spread to the most fashionable women in the United States. Even the style icon and American First Lady Jackie Kennedy wore them (though she never admitted it).

High-end wigs were “often made in Europe from European hair,” Petrulis says. But by the mid-1960s, the source of raw hair shifted from Europe to Asia. An abundant and cheap supply of shorn hair from China, Vietnam, India, North and South Korea transformed wigs from a high-end luxury to a mid-market accessory for Western women.

Selling wigs to consumers in Western countries brought much needed foreign currency into South Korea. But where did all this hair come from? The obvious answer is, of course, directly from the heads of Korean women like Kang Chae An.

“The hair collectors would come to the neighborhood yelling ‘hair collection!’,” Kang recalls. “Collecting hair was so popular that hair collectors would even go to hair salons. If the hair was in good condition, the hair stylist would tie it in a ponytail and hang it on a wall for the hair collectors.”

People from all walks of life engaged in the hair trade. Chang Sun Hwa, for example, was born in Seoul to a well-to-do family of doctors in 1954 and enjoyed a comfortable upbringing that was unusual for the time. “My grandma did not cut her hair but collected the hair that fell on the ground after combing it,” Chang explained. “She sold her hair after she collected enough.” Nonetheless, Chang remembers her grandmother’s long hair as always styled in a jjok meori, a chignon bun worn by women during the Joseon Dynasty. For women who wanted to keep the appearance of long tresses, thinning discrete sections of their hair was an alternative solution.

But despite its profit potential, parting with one’s hair was not easy. When Chang received her first haircut at the start of high school (as part of a national mandate to usher South Korea into modernity), she described the feeling as similar to having a limb removed. Her testimony reflects the sentiments and sacrifices of other Korean women who gave up their hair so that women around the world could feel beautiful and the nation could forge a modern and industrial image.

It worked. Over the next decade, the wig industry boomed in South Korea. In 1964, wig sales totaled a measly $14,000. By 1970, wigs brought South Korea over $93 million in annual revenue. At its height, wigs made up 9.3% of South Korea’s exports and was the country’s number two export.

At first South Korean hair was just a raw material exported to wig manufacturers abroad, but in a matter of years, South Korean homegrown factories cropped up to process hair into wigs domestically. By the late 1960s, the South Korean wig factories relied mainly on imported hair from China and other neighboring countries for a lower price. This new phase of success relied on the cheap and quality labor of thousands of young women.

Kang remembers seeing teenagers living and working at wig factories when they could not afford going to school. More than the experience of selling hair just once, working in a factory provided these young women with a relatively steady source of income—an unprecedented level of economic achievement.

But these women were exploited for their labor, says Petrulis. “Owners would train women to work only on a single step in the production process so it would be harder for women workers to move into management, and so it would be harder for a woman to take skills from one factory to another for higher wages. Women also were usually paid by the piece (rather than by fixed salary), and sometimes worked from home factories, so that individual workers carried a lot of the financial risk if production slowed down.”

Injustice in the wig trade, along with astounding economic profits, both stemmed from the fact that “the gap between what women wig workers were paid and what women wig wearers spent on their products was huge,” Petrulis says. Factory women retaliated against these conditions. The 1979 all-female YH labor union famously occupied the wig exporter YH Trade in protest of sudden layoffs and demanding back pay (the equivalent of $1.67 a day in today’s money). Though riot police forcibly removed the women and none of their demands were met, their bravery laid the foundation for the Korean Women Workers Association, Korean Women’s Associations United, and Korean Women’s Trade Union which are still actively fighting for fair working conditions for South Korean women today.

The global wig industry is still booming—growing by thirty percent in 2020, likely fueled by what the Atlantic dubbed “a near-perfect mass hair-loss event” during the pandemic. The source and labor that goes into making a wig remains largely female, though has shifted towards India, China, Thailand, and Bangladesh. The popularity of wigs and hairpieces provide economic opportunities to thousands of women in these countries, as it did in South Korea, though at similarly heavy costs.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook