Remembering Caesar, Colonial Virginia’s Enslaved Chocolatier

In Robert E. Lee’s birthplace, Dontavius Williams honors an unsung chef.

In Gastro Obscura’s Q & A series A Seat at the Table, we speak with people of color who are reclaiming their culinary heritage and shaping today’s food culture.

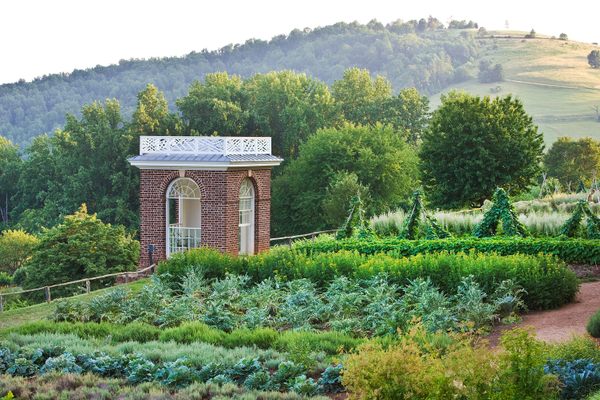

At Stratford Hall, the plantation of the Lee family and the future birthplace of Confederate general Robert E. Lee, lavish Christmas dinners would end with Virginia’s White elite gathering around small, steaming cups of hot chocolate. The drink was sure to impress the guests, as the Lee family owned one of the colony’s few household chocolate stones for turning imported beans into a luxurious brew.

Said hot chocolate was the work of one of Virginia’s few chocolatiers: a man known only as Caesar, the enslaved African-American chef whose virtuosity helped make Stratford Hall a centerpiece of Virginia’s high society during the mid-1700s.

“It’s a life mission to be able to help the world understand that people like Caesar existed,” says historical interpreter Dontavius Williams. Several times a year, Williams dons Colonial attire and fires up the hearth at Stratford Hall. Williams is on a quest to show how the brilliance of African-American cooks shaped the South, a mission that’s especially radical within the birthplace of the most prominent Confederate leader.

Caesar was born in 1732, and helmed Stratford Hall’s kitchen starting in the middle of the 1700s. He managed one of the most extravagant kitchens in the colonial South, catering to the needs of the Lee family at all hours of the day. At banquets, he would ply up to 100 guests with multiple courses of fanciful delicacies. Caesar’s ability at chocolate-brewing was exceptional, but he also mastered everything from fancy cakes to oyster stew to roasted pheasant. His kitchen operated at the cutting edge of Southern culinary fashion.

Williams’ journey to telling Caesar’s story began when, as a college student, he volunteered at a plantation museum in South Carolina. Around 2015, Williams founded The Chronicles of Adam, a project in which he researches the life of a historical enslaved man named Adam and does demonstrations—often involving cooking—to show how he might have lived.

In 2019, historian Dr. Kelley Fanto Deetz, author of Bound to the Fire: How Virginia’s Enslaved Cooks Helped Invent American Cuisine and Vice President of Collections and Public Engagement at Stratford Hall, invited Williams to cook at the museum. Since then, he has become the resident African-American Foodways Interpreter. Drawing on Stratford Hall’s preserved 18th-century cookbooks and bills of fare, Dr. Deetz’s research, and other primary and secondary sources, he brings the work of African-American cooks to life at the museum’s Juneteenth celebration to programs like “Caesar’s Chocolate: The History and Legacy of One of Virginia’s Earliest Chocolate Makers,” which paired a discussion of Caesar’s work with a demonstration of historic chocolate-making techniques.

Gastro Obscura talked with Williams about Caesar’s culinary skill, the influence of African-American foodways on Southern cuisine, and changing people’s minds with food.

What role do you think food plays in historical interpretation?

It’s the great leveler [and also] the great divider … We all eat. We just eat differently. And I’m able to use those foods and those commonalities to be able to break down the barriers between people, and to eventually change their hearts.

I’ve had some of the most racist people come through. They come to the site of the birthplace of Robert E. Lee in their Confederate caps, and they’re coming to honor the [General] of the Confederacy … And whenever they come in the kitchen, their bubbles are burst a little bit, [but] they leave so much better. They see the fatback [bacon] on the table. They see something that they remember from their grandmother’s house.

In that type of situation, what might you have said or done to change their attitudes?

I pull a page from my mentor Nicole A. Moore. She said, in America, especially in the American South, we eat more closely to the diet of the enslaved than we do the big house. Whenever [guests] come in and say, “Oh, my grandma used to make this,” I’m like, “You know something? If you think about the diet of the enslaved, our diet in the 21st-century South is very close.”

I’m able to talk about food rations that were given to the enslaved on certain plantations. And I ask them about other vegetables and fruits that, as Southerners, they may like.

I’m like, “So do you like okra?” “Yeah.” “What about black-eyed peas?” “Yeah.” “Did you know that black eyed peas were not considered fit for human consumption?” They’re like, “Wait, no, I love black-eyed peas and hoppin’ john!”

Okra and black-eyed peas are both native to West Africa. Were there ways, when you were looking at the recipes served in Stratford Hall, that you saw West African influences in what Caesar was cooking?

Curry chicken, peanut soup, okra and red tomatoes, things like that: those are direct recipes from West Africa. The black-eyed peas, the cow peas, all those things that were not seen as fit for human consumption [in the 1700s] were actually consumed, and now are fan favorites of Virginia and of our country.

What are some aspects of Caesar’s work that you think are really remarkable?

The fact that Caesar was one of three chocolate makers in the colonies was amazing.

It’s been said that Caesar conducted that kitchen as a conductor would do an orchestra, from working with scullery maids to working to bring in wood and water, to ensuring that the produce was always on point and the supplies never ran out. Caesar had to have a lot going on in his brain. I’m able to help to break that mentality of the public that the enslaved population was a dumb population.

What do we know about his day-to-day life?

His day starts before dawn, and it ends well after dusk. As head cook of the plantation, much like a head chef that you would see in a five-star restaurant today, the weight was heavy. The difference is, a head chef gets paid. [Caesar] ensures that everyone in the big house is fed and satisfied from breakfast until the last chocolate drink at the end of the night.

But during the holiday season, he goes into overtime … People are coming in to visit and they’re not leaving in 24 hours or in two or three hours; they stay for days and weeks and months. If you were Caesar, or if you were one of those cooks, you’re working so hard to make sure that this family is satisfied, but you have January 1 coming. [Enslaved] families are broken up on that day. People are getting rented out, people may get sold, because that’s the time where the plantation owner has to balance the books.

Do you know if Caesar received recognition for his work from people locally?

I haven’t seen anything recorded. You don’t see a lot of information out there about these guys unless it’s been dug up by historians researching their lives, [or] they do something that’s completely amazing. Caesar was just doing his job. That’s the downside of slavery, right? You work your whole life, and you never get recognition for the wonderful things that you do.

What do you think are some lessons that you’d like people to learn from Caesar’s story?

There are a lot of people who make differences, whose names we never know. But because we do know Caesar’s name, I’ll scream it from the mountaintop every time I walk into that kitchen. He’s not there physically, but every time I walk into that kitchen at Stratford Hall, I say, “Good morning,” or “Good afternoon, Caesar. Thank you for letting me use your space.” He may not have viewed that space as something sacred to him, but for him to be able to survive and thrive, even in the face of slavery, shows me that there was something that kept him motivated.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook