Remembering When Fish Rode the Rails

For decades, salmon, catfish, and trout traveled in America’s fleet of “Fish Cars.”

On a summer day in 1873, a retired Unitarian minister prepared his tea and dinner aboard a westbound train outside Omaha, Nebraska. Dr. Livingston Stone and his assistants had spent the last six days since their departure from New Hampshire sleeping on cots suspended over a covered, zinc-lined fish tank that took up a third of the refurbished Central Pacific fruit car. Twenty other tanks and tin cans of various sizes took up almost all of the remaining space (along with two casks of ocean water, an ice chest, six large cases of lobsters, and half a barrel of live moss).

Without warning, months of hard work ran off the rails. Water quickly filled the car, sweeping its cast of bruised humans, perch, catfish, and trout into the relatively safe shallows of Nebraska’s Elkhorn River. Climbing atop their now-submerged car, Stone and his men took stock of the bridge collapse that had killed at least one of the train’s crew. Ever the faithful servant, the waterlogged aquarium chaperone left the scene of the accident to immediately telegraph his boss, the head of the United States Fish Commission. By morning, Stone had received a reply, asking him to return east immediately—to pick up a load of 40,000 shad and try again.

Ever since fish flesh first met tastebuds, landlubbing humans have endeavored to find ways to finagle fresh meals from the nearest coast. But in Dr. Stone’s America, transport of live fish by rail had only just become a possibility by 1869, when the Transcontinental Railroad officially opened for business with the driving of the ceremonial 17.6-carat golden spike in Promontory, Utah. Having resigned from the ministry in 1868—on doctors’ orders to spend more time in nature—Dr. Stone, an amateur trout specialist, soon found himself elected secretary of the American Fish Culturists’ Association.

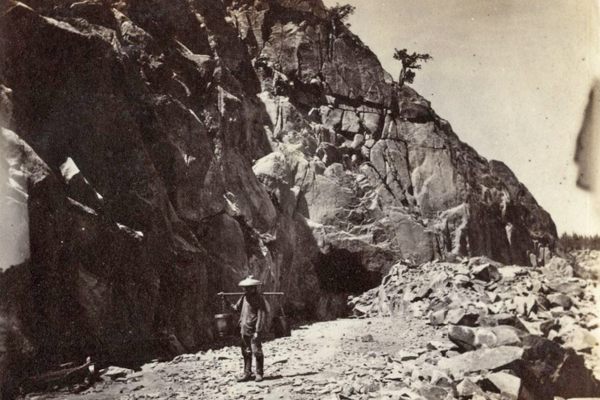

By 1872, Stone received a more federal calling: establishing hatcheries at the behest of the newly founded Fish Commission. Stone spearheaded the creation of the first such hatchery (Baird Station, named after his boss) on California’s McCloud River, where he personally packed cultured chinook salmon eggs in layers of moss before driving them to the nearest rail station, 22 miles away in Redding (through the Indigenous territory of Winnemem Wintu, whose residents viewed the hatchery’s arrival with profound skepticism). A San Francisco-based New Zealander would later ship some of these eggs as far afield as the Auckland Acclimatisation Society—one of many such organizations at the time dedicated to the import of foreign creatures into European colonies, in order to “enrich” the local flora and fauna.

Both Stone and the Fish Commission felt justified in shepherding these hapless creatures across thousands of miles, because they could no longer deny the reality of dwindling wild fishery stocks along the Eastern Seaboard (brought about not just by overfishing, but by the construction of dams that cut off access to upstream spawning grounds). By establishing Eastern food staples in the American West, Stone and his contemporaries ascribed to a form of conservation typical of the era, in which scientific interventions could help both nature and civilization with no apparent downside.

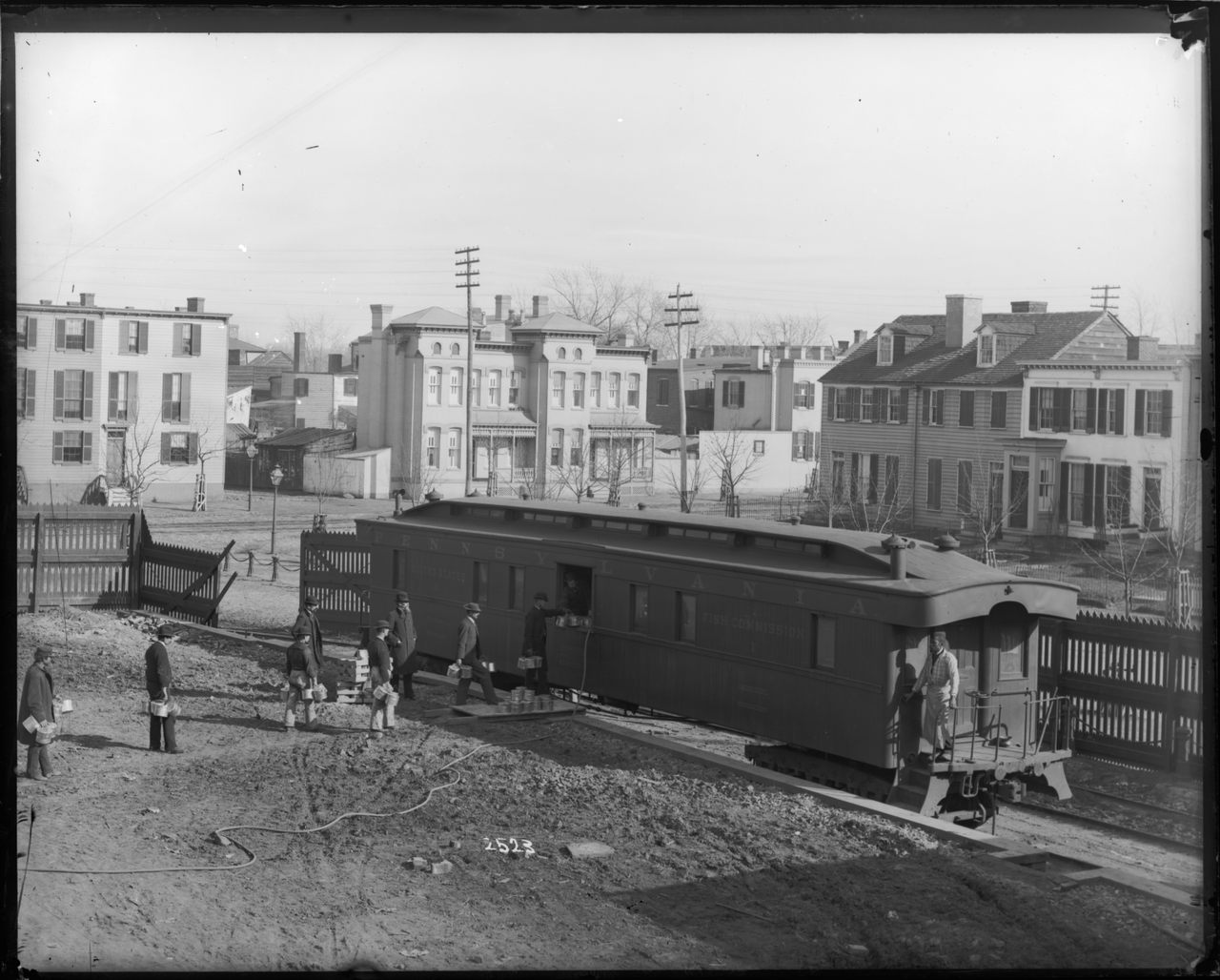

Seventeen days after his hard right turn off a bridge, Stone left D.C. again—this time, with eight 10-gallon milk cans, each containing 5,000 juvenile shad destined for the Sacramento River. En route, a cold snap in Utah drove one of Stone’s assistants to heat iron couplings in the train’s furnace; these couplings then heated the “reserve water” added to the jugs, two degrees at a time, to keep the shad alive (without also flash-frying them). But this ad-hoc approach—in 1879, Stone hired fellow passengers to babysit his jugs of striped bass fry—could only go so far. By 1881, the U.S. Fish Commission debuted a custom-designed baggage carriage as its first-ever official “fish car.”

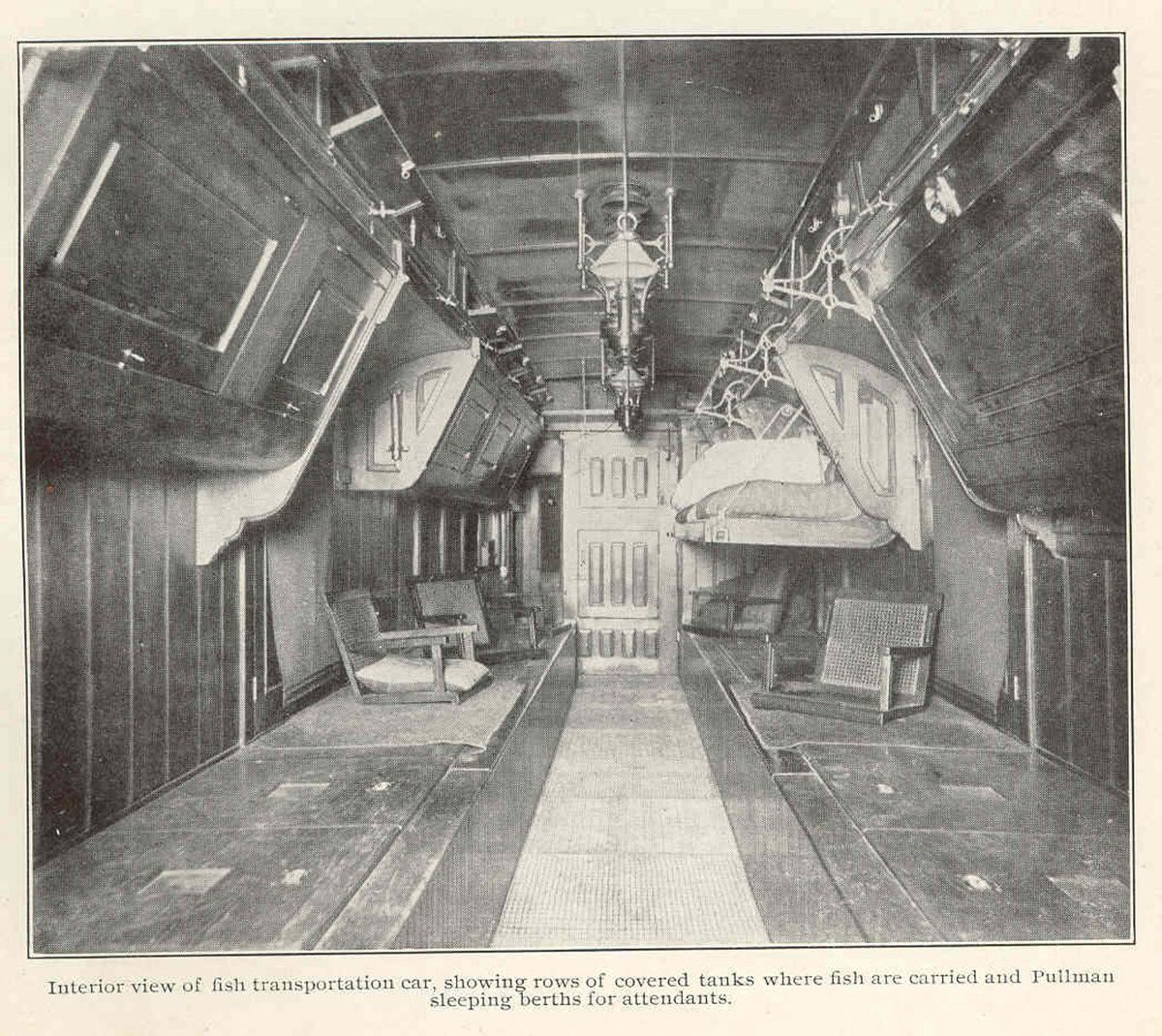

Over the next half-century, the U.S. government commissioned nine more, each more advanced than the last: cedar tanks, ice compartments, mechanical air pumps, staff accommodations, and all the structural reinforcements required to carry tens of thousands of pounds of pike, perch, whitefish, carp, and crab. When “Fish Car No. 10” rolled off the line in 1929, it came with its own generator and space for as many as half a million (one-inch-long) fish. This 81-foot behemoth joined a fleet that had, in 20 years, transported more than 72 billion fish more than 2 million miles.

That same year, another car rolled off the line at Pullman Car Works on Chicago’s South Side. Unlike the federal fish cars, the “Nautilus” exclusively serviced the needs of Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium, which opened on the shore of Lake Michigan in 1930 with saltwater exhibits that had been stocked by 20 round-trips to the ocean and back. Chicago’s status as a rail hub gave the Shedd prime position, with a private rail spur that allowed exotic collections to be delivered to their back door.

But it was precisely the Shedd’s niche, scientific mission that allowed the Nautilus to do what its government counterparts could not: survive. The Nautilus collected specimens for three decades before handing off its schlepping mantel to its successor, Nautilus II, which soldiered on until 1972. Fish cars, meanwhile, found themselves outdated as a booming highway system allowed trucks to transport the same cargo with greater freedom at a fraction of the cost. By 1947, Fish Car No. 10’s innards were disassembled and shipped off to the hatcheries it once served.

By the 1960s, hatcheries began to explore the new world of “air stocking,” which entailed loading up thousands of hatchery-grown trout and bass into the bellies of fixed-wing planes, which would then unload their scaled charges during low-level fly-bys (with fingers crossed that 95 percent would survive). To this day, aquatic air-drops into inaccessible mountain and backcountry lakes make up a huge part of recreational sport fishing. More recently, by 2007, the whimsically-named “Whooshh Innovations” began to develop a so-called “fish cannon,” designed to gently jettison beleaguered salmon past hydroelectric dams, like some kind of pneumatic-tube-cum-ichthyological-Hyperloop.

Stone’s original hatchery, meanwhile, continued to cast a long shadow. The building of the Shasta Dam during World War II had flooded 90 percent of the traditional land of the Winnemem Wintu, the same tribe whose knowledge and labor had helped create Stone’s hatchery in the first place. In 2005, however, the tribe received an unexpected message from New Zealand.

As it turns out, local Māori had been caring for the descendants of the McCloud river salmon for the past century and a half, as they swam happily through the Rakaia River. Five years later, both tribes convened outside of Christchurch and hosted a four-day feast to celebrate the salmon’s eventual return. The tribe even went so far as to fundraise for DNA testing to prove that these fish had, in fact, originated from their lands—so as to dissuade the U.S. government from blocking the homecoming of what could now, in a surreal irony, be considered a “non-native” species.

The Winnemem Wintu continue to organize for the return of their sacred salmon. Meanwhile, in July 2022, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service drove tens of thousands of winter-run Chinook salmon eggs—collected from the Livingston Stone National Fish Hatchery, just outside of Redding—into the waters upstream of Shasta Reservoir. And yet, “It is not a species reintroduction program,” the agency clarified. Rather, the looming threat of climate change and drought had prompted the agency to relocate the now-endangered salmon into slightly cooler waters.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook