In Greenland, A Popular Record is Owned by 1 Out of Every 12 People

Members of the band Sumé, featured in the German doc, Sumé—The Sound of a Revolution. (Photo: Courtesy of Mindjazz Pictures)

A version of this post originally appeared on the Tedium newsletter.

What does your pop culture look like when there’s not a lot of population to spread culture? This is an interesting challenge in a lot of ways for the world’s most-sparsely-populated country, Greenland.

With a population of less than 60,000 and a land area larger than Mexico, Indonesia, France, or Germany—though with nearly all of that area covered in a giant block of ice—Greenland is most definitely a region where creating a unique, modern culture can be a bit of a challenge.

It’s a country where the largest city, Nuuk, would be considered a small town in any other large country. (In 2015, its census listed 16,992 people.) But despite that, Greenland has definitely been able to produce a unique modern culture of its own. And when something is popular in Greenland, it infiltrates the population in a way that is all but impossible elsewhere. In an average year, 10 to 15 albums are released in the country, according to the country’s official website. A success for a band in the country is an album that sells around 5,000 units locally, which means that you have to sell one album for roughly every 12 residents of Greenland.

If you were to sell a proportional level of units in the United States (where tens of thousands of albums get released yearly, by the way), you would need to move 25 million units—something only one musician, Michael Jackson, has done in the U.S. alone.

The pop renaissance in Greenland began with a band called Sumé, a group that first put the country’s heritage on the modern musical map.

The village of Nuuk. (Photo: Oliver Schauf/Wikimedia Commons)

If you were a music fan living in Greenland in the 1970s, you most assuredly owned a copy of Sumé’s Sumut. The record was revolutionary for a number of reasons. For one thing, it was a rock album in Greenland, sung in Greenlandic rather than Danish or English. It also emphasized a message of freedom and sovereignty in an area that was treated as a second-class citizen to Denmark, which had colonized the region in the 1800s—taking over from Norway, which had colonized the land six centuries prior. The album was a huge success—and a quietly political record.

The cover art alone marked a victory for the country’s culture; it depicted the violent struggle between a legendary figure in Greenlandic culture named Qasapi and a Norse chief named Uunngortoq. The basic story of the battle between the mythic characters can be read in Google Books, but the long and short of it is that Qasapi won handily. (The man who created the artwork is equally legendary in Greenlandic culture, by the way; Aron of Kangeq was a 19th-century Inuit who went from being a seal hunter to the country’s best-known artist, thanks to a cultural reassessment of his work during the 1960s.)

The cover of the iconic first album. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

But the most potent symbol part of Sumut was the fact that Sumé was singing songs in Greenlandic. It was the band’s way of showing off some native cultural identity when Greenland was in severe danger of becoming culturally assimilated as a part of Denmark—a strategy that Denmark began to encourage after World War II by offering Greenlanders Danish citizenship and taking a more active role in the country’s affairs.

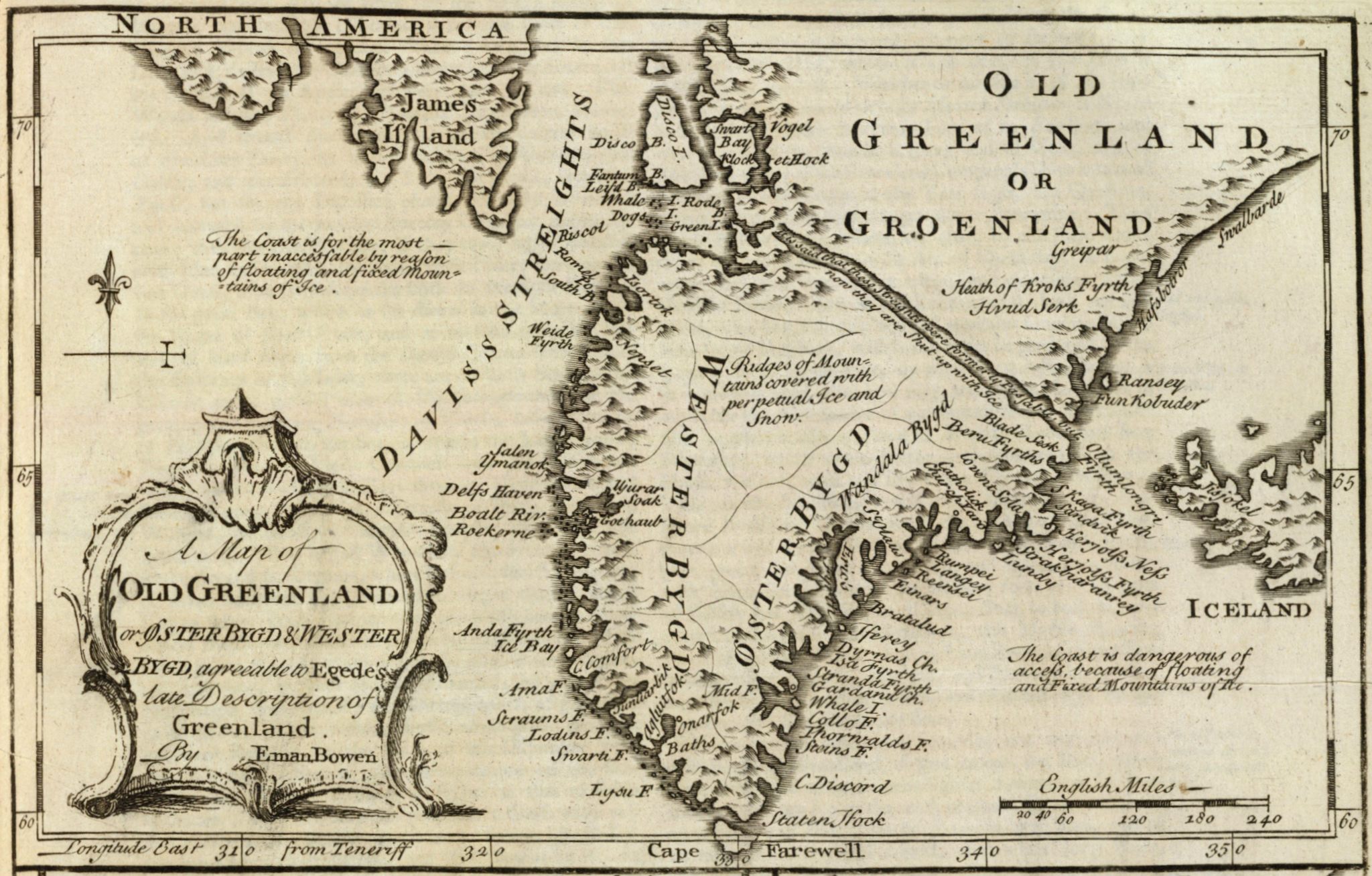

(The assimilation is interesting to note when looking specifically looking in geographic terms, by the way. Nuuk is closer to Toronto than it is to Copenhagen, and the region’s Inuit background clearly creates cultural ties between the island and northern Canada. However, it’s challenging even now to travel to Greenland without going through Iceland or Copenhagen first, meaning it’s easier to head to Greenland through Europe than through North America.)

That music, implicitly critical of the Danish government, quickly became associated with an independence movement in Greenland, one that saw success just a few years later. In 1979, Greenland was given a degree of home rule, allowing the country to start its own parliament and control over some internal policies. That home rule has expanded ever since and is expected to turn into full independence at some point.

Sumé, as a band, didn’t last nearly that long, breaking up in 1977 after three albums. But their legacy long outlasted the band itself. In 2014, the band was the subject of a documentary, Sumé: The Sound of a Revolution, which makes the case that Sumé started the home-rule conversation in the country.

“Among other issues, Sumé’s lyrics put [feelings] of alienation, loss of direction, and the reestablishment of own self-esteem into words and questioned people’s indignation towards authority,” director Inuk Silis Høegh said of the band’s importance to Greenland. “I think all of those issues are just as much in play today as they were 40 years ago.”

That’s a pretty good way to sell a rock record, don’t you think? Good news for you: The full album is available on YouTube.

An early, erroneous map of Greenland. (Photo: Emanuel Bowen/David Rumsey Collection)

Over the years, a variety of musical acts have been able to stake a claim of their own in tying outside culture to local concerns.

A good example of this is Nuuk Posse, pretty much the country’s greatest gift to hip-hop. Active since the 1980s, Nuuk Posse has built a reputation for socially-conscious (and good) music, and the group—made up of Inuits, the largest population sector in the country—has managed to remain relevant in the country for decades.

Cover of Nuuk Posse record. (Photo: Discorgs)

Also from Nuuk but mostly based out of Copenhagen these days is Chilly Friday, a band with more of a grunge sound. Don’t believe me? Compare this Bush song to this Chilly Friday song.

Perhaps the most popular modern act in Greenland these days is Nanook, an indie pop band, led by a duo of brothers, that has an acoustic-driven sound comparable to early Coldplay. The band comes from a musical family, one that runs one of the largest record labels in the country, Atlantic Music. (No, not that one, the other one.)

Slightly easier for non-Greenlanders to get into is the Qaqortoq-based Small Time Giants, an alternative rock band from the country that mostly sings in English. While there is some heart-on-sleeve stuff in their songs, it’s hard to miss the political messages in like “3-9-6-0.” Sample lyric: “We sold all we had at the end of the rainbow/we lost all we had when the sun set.”

And while Greenland doesn’t have its own version of American Idol or anything like that, its ties to Denmark come in handy on that front. Julie Berthelsen, a pop star in Denmark whose voice throws shades of Kelly Clarkson, grew up in Nuuk and found major success after being featured on the Danish edition of PopStars. She didn’t win, but she became famous anyway.

A couple of other things you might be wondering about when it comes to Greenland: Yes, it has a film industry; yes, it has publicly available internet access; and yes, there is a fairly robust media industry in Greenland.

Multi-lingual signage in Greenland. (Photo: Benutzer/Wikimedia Commons)

There are some wrinkles to each, however. Greenland’s film industry, while having led to numerous productions at this point, is still incredibly young, with the first film fully shot and produced in Greenland, Heart of Light, only coming out in 1998. The film had a little star power out front, with its lead character being played by Rasmus Lyberth, a well-known musician from Greenland, who is portrayed as an alcoholic in the film.

Poster for Heart of Light, the first major production made completely in Greenland. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The film industry, working from this starting point, has since produced dozens of films (including the Sumé documentary mentioned above), leading to Greenland Eyes, a traveling film festival that went to numerous countries between 2012 and 2015—including the United States.

Meanwhile, the country’s internet systems are fairly commonplace at this juncture, but don’t expect to spend all day watching Netflix. The American Enterprise Institute, a notable critic of net neutrality, notes that 90 percent of Greenlanders have access to the internet in their homes, largely through ADSL lines, but that the not-insignificant needs for internet access for things like telemedicine and education have required the country’s primary internet provider, TELE Greenland, to prioritize access to public services.

In other words, Greenland doesn’t have net neutrality.

“The cap is in place so that heavy users do not monopolize the network to the detriment of others,” AEI’s Roslyn Layton writes. “These practices also allow TELE Greenland to recover extremely high capital and operating costs to build and maintain networks. To be sure, users who want to stream video can pay for a package with a higher speed and data cap.”

Befitting Greenland’s role as an outsider nation on the world stage, the island tends to be the subject of a lot of outside-in cultural depictions, rather than the other way around. But too often, these depictions fail to actually tie in the native culture, instead overplaying the whole icy, remote element of the country.

Most famously, Happy Days lead Richie Cunningham joined the army and found himself stationed in Greenland for two seasons—conveniently, allowing Ron Howard to leave the show to become a director. Despite this remote assignment, he still managed to marry his girlfriend Lori Beth and have a kid with her. (No word on if Richie partook in the local culture while he was there.)

And Greenland often provides a setting for video games. For example, the PC-based game series Penumbra largely takes place in Greenland, using the remote location to play up the horror elements of the game. The Playstation game Wipeout, meanwhile, used Greenland as a setting for some of its races.

More recently, Animal Planet pointed out the fact that there’s gold and other noteworthy minerals in the glaciers, launching a series called Ice Cold Gold a couple years ago.

But the most depressing emphasis of Greenland as a nation that’s only good for ice and cold is yet to come. Syfy is currently working to produce 51st State, a series that imagines Greenland being purchased by the United States and turned into a giant prison for all of its extra inmates.

There may only be less than 60,000 people there, but could we perhaps do a better job representing their pop culture in our pop culture?

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook