How to Make Nobel Ice Cream, the World’s Smartest Dessert

You may not be a prize winner, but you can eat like one.

At the greatest dinner party on earth, one thing is always on the menu: fireworks, with a side of dessert. At the end of every Nobel banquet, held yearly on December 10, servers descend a grand staircase in Stockholm’s City Hall bearing platters of sweets, surrounded by spitting sparklers.

It’s an appropriately grand finale for an event celebrating groundbreaking scientists, artists, and peacemakers. Perhaps it’s also a tongue-in-cheek reference to the person who paid for the festivities. It’s suspected that, before his death in 1896, the inventor of dynamite Alfred Nobel deeply regretted the wartime usage of his brainchild. So he dedicated the majority of his fortune to funding those who artistically, spiritually, and scientifically advanced the human race.

The reward consists of prize money and a white-tie party with Sweden’s royal family. The first banquet in 1901 came capped with a very special dessert: Nobel ice cream. Banquet organizers often served glorious icy confections for dessert throughout the 20th century, but it was during glace Nobel’s unbroken run between 1976 and 1998 that it became one of the high points of the event.

One guest, Cornell physicist David Mermin, attended a banquet in the twilight of the Nobel ice cream era. He describes the famous “Ice Cream Parade” thusly:

The descent of the third course (Glace Nobel) left me gaping in astonishment. It began, quietly enough, with a dimming of the lights. Then two great canopies flutter down out of nowhere and manage to form a kind of roof within the roof over the great staircase which is suddenly engulfed in a cascade of waist-deep white cloud … there appear at the top of the still-smoking stairs 150 waiters bearing massive glowing trays of ice cream for the revellers below. Waiters descend, singers ascend, spoons clink, plates clatter, and a woman’s voice whispers in my ear, “You’re the last one, would you like everything left on my tray?” “Yes,” I gasp gratefully, and soothe my aching throat with a triple portion of panache de sorbet aux mûres sauvages des champs et de parfait à la vanille…

There’s no official recipe for Nobel ice cream. It consisted of elderberry-strawberry parfait one year and blend of chocolate ice cream and blackberry sorbet the next. The only consistent factor was the great pomp with which it was served.

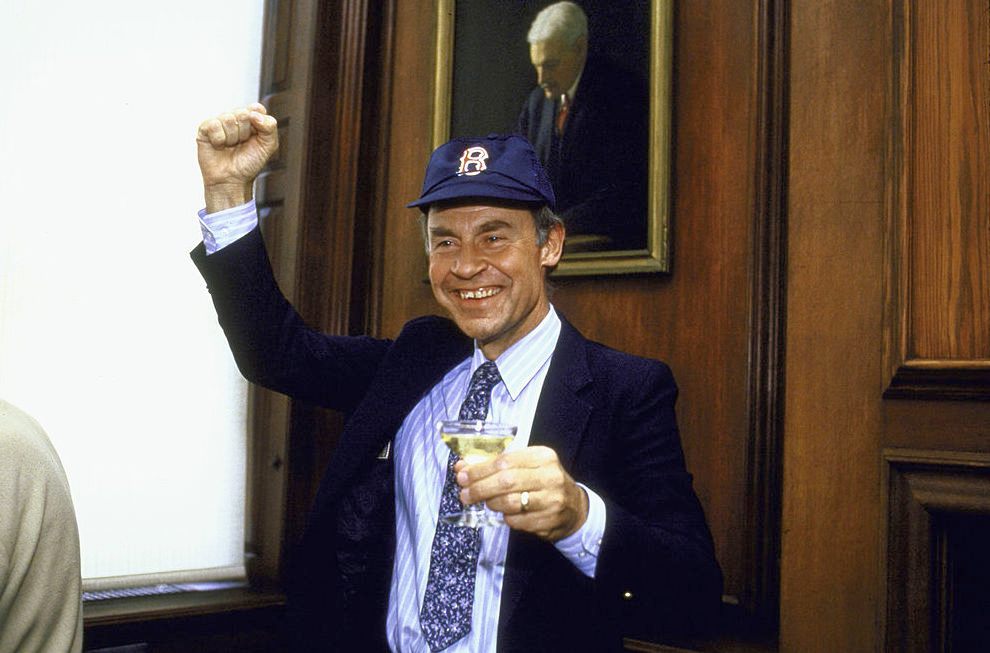

Dudley R. Herschbach, one of the three winners of 1986’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry, still remembers the ice cream parade with fondness, even 35 years later. “It’s super-duper,” he laughed when describing it to me over the phone. Attending a Nobel banquet is only a portion of a grueling week-long event, filled with ceremonies, speeches, and lectures. Herschbach, a professor emeritus at Harvard who won the Nobel in recognition for his work studying chemical reactions with molecular beams, didn’t mind the hustle. “I was 54, and pretty spunky then,” he said. But even the most jaded academics, over the years, regarded the ice-cream parades with almost childlike wonder.

After all, as Hershbach noted, “who could be unhappy” when faced with ice cream and sparklers? While he couldn’t immediately recall the flavor of the ice cream at 1986’s banquet, a quick consult with his wife revealed some details. “My wife, Georgene, says the ice cream was blue, with berries,” he said. Georgene Herschbach, herself an associate dean at Harvard, wore blue that night. So did the queen of Sweden, whom she sat across from at the banquet table, while Herschbach sat across from the king. “The blue ice cream gave all of us blue teeth!” Herschbach said.

Ice cream came off the menu in 1999, when the banquet organizers allowed their chefs to expand beyond the then-traditional dessert. These days, feasts feature much more by the way of Nordic cuisine than the French staples of yesteryear. But while the words glace Nobel haven’t shown up in a while, guests still enjoy parades with servers bearing dishes like “chocolate silhouette with nougat and sea buckthorn explosion.”

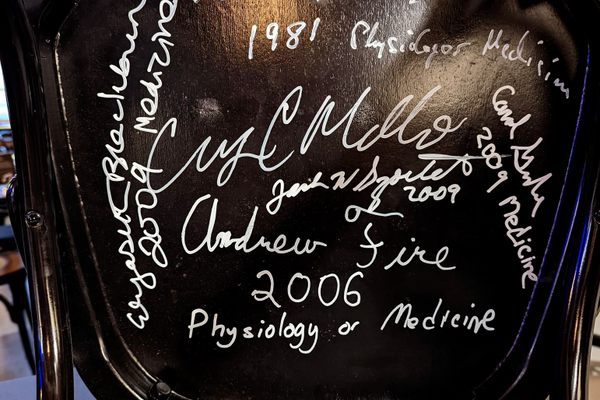

But the ice cream is not lost to history just yet. Those with deep pockets can actually eat recreated, historical Nobel banquets within Stockholm City Hall itself, in its basement restaurant. At Stadshuskällaren, chefs are on-call to reproduce banquets from any year of Nobel history. Which means you and nine other wealthy friends can feast on 1982’s banquet, where writer Gabriel García Marquez dined on marinated reindeer with mustard sauce, or 1979’s saddle of veal, which would have been served to Mother Teresa had she chosen to attend. Both banquets ended with magnificent parfait glace Nobel.

Nobel ice cream is also available for those without PhDs or penthouse money. At the Nobel Museum’s own bistro, the ice cream appears as a tiny molded bombe. Many Nobel banquets featured bombes, perhaps another gruesome joke at the expense of Nobel and his dynamite. Popular in the 19th century and enduring well into the 20th as a staple of fine dining, bombes often consisted of creatively flavored layers of sorbets, ice creams, custards, and sherbets that were often elaborately decorated and presented with a flourish.

Occasionally, the ice cream appears on the bistro menu as a parfait in a large wine glass. Made in collaboration with Daniel Roos, a chef who often oversees the banquet dessert, it consists of vanilla ice cream and raspberry sorbet. The raspberry sorbet and accompanying garnish is meant to evoke Sweden’s fruitful crop of arctic berries each year. The treat also comes with a gold-foil wrapped coin emblazoned with the face of Alfred Nobel: your very own Nobel prize.

Nobel Ice Cream Bombes

- Serves 4

Ingredients

- 1 cup raspberry sorbet

- 1 cup vanilla ice cream

- Whipped cream, raspberries, cape gooseberries, sprigs of mint, and chocolate-foil coins for garnish

Instructions

-

Prepare four molds for your bombes. They can either be old-fashioned gelatin molds, or even ramekins, so long as they are around half a cup in volume. Wash them, dry thoroughly, then place them in the freezer until they are completely chilled.

-

While the containers are chilling, take out the raspberry sorbet and allow it to soften. When the containers are icy to the touch, add about ¼ cup sorbet to each. With a sheet of plastic wrap, press the sorbet layers flat so that the entire bottoms of the mold are covered and no gaps or bubbles remain. Put the molds into the freezer, and allow them to sit until the sorbet has hardened, around an hour.

-

When the sorbet is nearly done chilling, remove the vanilla ice cream from the freezer and allow it to soften until scoopable. Then, add around a quarter cup of the vanilla ice cream to each of the molds on top of the raspberry layer, smoothing it flat with the help of more plastic wrap.

-

Return the molds to the freezer and allow them to chill until firm, at least an hour and a half and up to overnight.

- To unmold, dip the bottoms of the containers into hot water, then quickly tip them over onto cold plates. Garnish with whipped cream, raspberries, gooseberries, mint, and a chocolate coin.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook