Scientists Just Geolocated a Victorian-Era Butterfly Using Its Genome

Their work affirmed the insect’s taxonomy too. Because you can’t spell “named” without D-N-A.

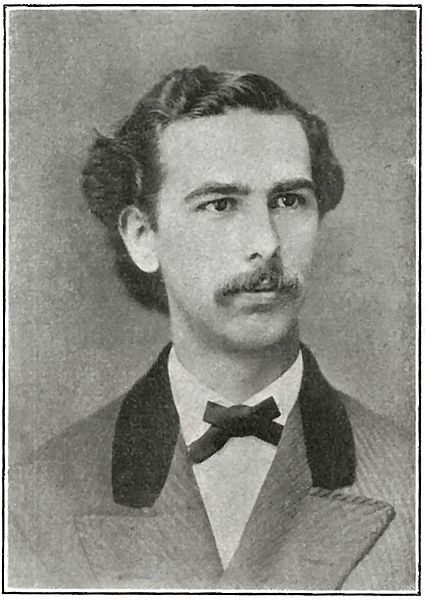

On July 13, 1871, Theodore Mead found a butterfly.

An American naturalist and entomologist, Mead snared the specimen—which would eventually be known as the western branded skipper (Hesperia colorado)—somewhere in the state that bears its taxonomic name. But like most collectors of his time, he didn’t document where he caught it. So for well over a century, the specimen collected dust on a shelf in Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, imprecisely catalogued because no one knew exactly where it came from.

That changed this year, after researchers studied the butterfly’s genome to figure out its geography. Their work—which was pre-printed (meaning it was published before it was formally peer reviewed) in the open-source journal bioRxiv this week, nearly a century and a half after the butterfly was netted—could pave the way for curators to include provenance data on musty specimens.

“Many old type specimens have no locality data associated with them at all,” says Andrew Warren, an entomologist at the Florida Museum of Natural History’s McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity and one of the paper’s authors. “This is a problem for species identification.”

The western branded skipper is found in much of the western United States, not just Colorado, leaving modern researchers with a range of possibilities for the Mead butterfly’s original home. It’s a good illustration of a major taxonomy problem for museums—one that occurs most frequently with specimens collected before 1970. (That’s the year when coordinate information—rather than location names, which can change—became standard info to include in the cataloguing process.)

“The further back you go,” says Lorenzo Prendini, an entomologist with the American Museum of Natural History in New York (who was not affiliated with this study), “the more of a problem it can be.”

Prendini says that collections over 100 years old often have vague geographic citations, like “Australia,” or outdated names, like “New Holland.” Some specimens have misspelled names attached to them.

Since Mead collected the butterfly nearly 150 years ago—and died 83 years ago—Warren’s team turned to the only testimony that can truly stand the test of time: DNA evidence. They set about extracting the butterfly’s genetic material in a way that didn’t cause the elderly specimen too much harm.

“The abdomen was removed from the specimen and soaked in a solution that allowed the DNA to ooze right out through the skin,” Warren says. “Then it was isolated from the solution and sequenced.”

The team collected a quarter of the specimen’s nuclear genome (its genetic building blocks) and its entire mitochondrial genome (which is often used to understand geographic distribution)—a sizable chunk of genetic material, considering the skipper’s age. Holding its genetic information up to a database of 85 other skipper butterflies (collected since Mead nabbed his in the late 19th century), Warren’s team found a match: The butterfly was caught in Lake County, Colorado.

Warren says this new research could provide a lasting framework for geolocating other animals that were stowed in museums long ago. “Using this approach,” he says, “it should be possible to pinpoint the origins of ancient specimens if they retain sufficient DNA.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook