The Gastro Obscura Guide to Cooking School-Lunch Classics

You’re the lunch lady now.

Though students are still studying for finals and finishing up their term papers, they’re not doing it on campus this year. Instead, dorms are empty, quads are deserted, and playgrounds are covered in caution tape.

Instead of cafeterias, students are now eating lunch in their own (or their parents’) kitchens, which, depending on the school, might be a step up or down. But a few schools have treats like no other, from an Albuquerque school district’s legendary peanut butter bar to a way of barbecuing chicken that has spread throughout Upstate New York. With prom on ice and graduations likely to take place over Zoom (if at all), our own kitchens can provide a taste of academia until school’s back in session. But whether your 25th high school reunion just got cancelled or you’re currently sweating over your grade point average, the following recipes can provide a dose of nostalgic comfort.

Jersey Dirt

University of Richmond, Richmond, Virginia

It started as a prank. In the early ’90s, Tina Lesher heard that the University of Richmond was holding a “Recipes From Home” contest. Lesher, the mother of a UR student, copied a pudding recipe from one of her cookbooks and sent it in as “Jersey Dirt,” claiming it was her daughter’s favorite dessert. Combining cookies, pudding, whipped topping, and cream cheese, the dessert was a winner.

One day, Melissa Lesher walked into the dining hall and saw Jersey Dirt (which she had never tried) on display, along with signs stating that it was her favorite. “I was mortified. I lost it. I turned the cards over so no one would see my name associated with it. I was livid,” she told the alumni magazine years later. But the dessert lives on at UR. Writes alumnus Catherine Amos Cribbs, “That glorious mix of cheesecakey pudding and crushed Oreos could calm an overstressed brain or soothe a broken heart.” For our overstressed brains and broken hearts, you can use this recipe from the university itself.

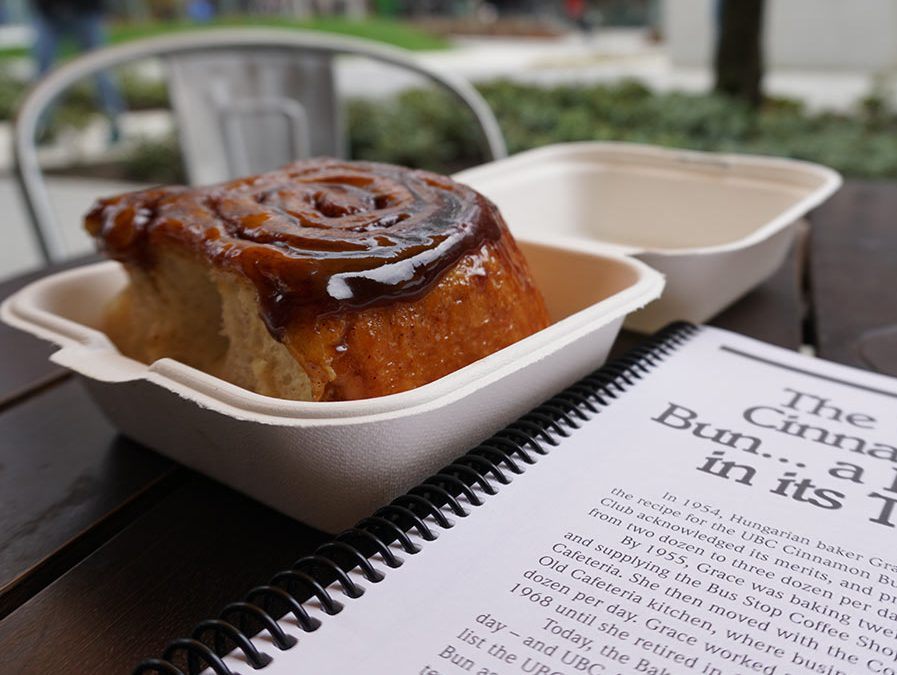

UBC Cinnamon Bun

University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

For students at the University of British Columbia, the ideal breakfast is one of the school’s famed cinnamon buns, typically made at the campus bakery. It all started with baker Grace Hasz, who began baking the famous buns for UBC in 1954 and didn’t stop until her retirement in 1971, at which point she was making 120 dozen per day. The university uses this recipe these days, which results in a “pillowy softness and caramelized edges,” writes Angelina Tagliafierro in UBC’s alumni magazine.

But that’s not enough for Eric Leyland. Hasz’s grandson went on a quest to remake his grandmother’s original cinnamon bun, which he maintains is different from the official version, seeing as “the buns should be almost black from the cinnamon, the smell overpowering,” he writes on his blog. After a number of tries, Leyland found a recipe that lives up to his memories of his grandmother’s specialty. As opposed to the university’s recipe, which makes 18 large buns, Leyland’s recipe, also available on his blog, fits into a 9-inch pan. As the rolls cool, he writes, make a cup of coffee, “then sit down, close your eyes and think of my grandmother.”

Chili and Cinnamon Rolls

Multiple Schools, USA

If you do end up making the UBC Cinnamon Bun, why not make some chili to go with it?

Though the combination of savory, beany chili and sticky-sweet buns might seem stomach-churning to some, the combination is actually a beloved school-lunch memory for students across the United States, from the Midwest to Montana and even the Pacific Northwest. Chili and cinnamon rolls may have started life as a hearty breakfast for loggers, before making the jump to schools. That heartiness is probably why they are a rare treat on school lunch menus these days—the mixture is something of a calorie bomb. But some restaurants still serve the combo, and no federal nutritional standards can stop you from making some chili (perhaps using this recipe from Southern Living) and soaking it up with a cinnamon roll.

Wellesley Fudge Cake and Peppermint Stick Pie

Wellesley College, Wellesley, Massachusetts

Wellesley is lucky enough to have two unique desserts tied to its name. One is old-school, going back to the late 19th century. At the time, fudge was the hottest new treat of the era, and it was especially popular at women’s colleges, where it was an illicit thrill for students to make in their dorm rooms after lights-out. A chocolate layer cake, topped with frosting that had been cooked much like fudge candy, became the specialty of Wellesley’s local tea rooms, which were often patronized by hungry students. In the 20th century, Baker’s Chocolate often included a recipe for Wellesley Fudge Cake on ads and packaging, and soon it became an old-fashioned dessert, instead of student fuel.

While the cake itself isn’t served often at Wellesley (it’s complicated to make at scale), the school provides its own recipe to bake at home, though they also recommend a recipe from Cook’s Country as an excellent modern take. But students at Wellesley these days may be more familiar with Peppermint Stick Pie, a simple and sweet dessert of peppermint ice cream spooned into a graham cracker crust and topped with chocolate that’s often served at campus events.

APS Gold Bars

Albuquerque Public Schools, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Former students in Albuquerque still dream about their Gold Bars. Once sold for 25 cents at schools, the simple unbaked bars consisted of peanut butter, actual butter, Rice Krispies or graham cracker crumbs, and powdered sugar with a chocolate topping. Recipes abound for Gold Bars online, especially as they’ve gotten rarer in schools themselves. And arguments abound too. Should Rice Krispies or graham cracker crumbs be the base? Should the topping consist of melted Hershey bars or Magic Shell? But most agree that the final result should taste something like a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup, and that they should be kept cold to prevent meltage in the Albuquerque sun.

Cornell Barbecue Chicken

Cornell University, Ithaca, New York

College students are crazy about chicken tenders, building websites to keep their fellow students informed of when they’re available and all but rioting when they’re taken off the menu. But the ancestor of the tender was the nugget, a prototype of which was created by Dr. Robert C. Baker, a Cornell food science professor who specialized in all things poultry. In a less-breaded flash of inspiration, Baker published a new way to barbecue broiler chickens in 1950 that endures not only at Cornell cookouts, but across New York State. Thanks to a vinegary, egg-enriched sauce used to both marinate and baste the broilers, the result is complex, tasty, and inexpensive enough to fuel generations of fundraiser and state fair attendees.

The original recipe has some pitfalls, due to the raw egg and the sheer amount of salt, but some still swear by it. Modernized versions of the recipe retain the egg, the magic ingredient that helps the sauce bind itself to the chicken.

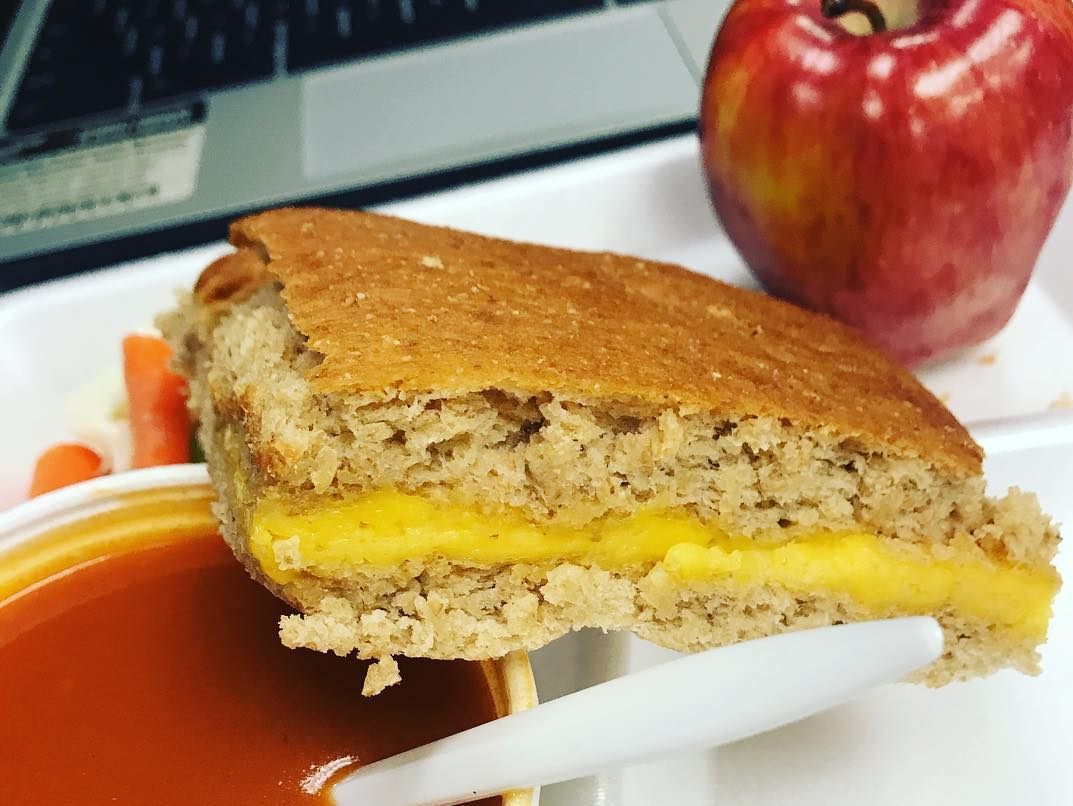

Cheese Zombies

Concord, California, and Yakima Valley, Washington

Though they are hundreds of miles apart, select students in California and Washington State have something in common: the Cheese Zombie. The concept is simple: a cake-like slab of yeast bread or a roll with a layer of creamy American cheese baked inside. (“Just like the undead, Cheese Zombies need time to rise,” notes the Yakima Herald.) Their origins are murkier. Did the bakers Decla Phillips and Helen Beloc invent them for Concord’s Mount Diablo High School in 1963? Or were they first whipped up when the Yakima School District received a huge amount of government cheese in the ’50s?

Whatever the source, the simple pleasure of a Cheese Zombie has lurched out of school cafeterias into local restaurants in both regions. And the Zombie is the rare example of an old-school favorite that’s still considered nutritionally acceptable to serve to young students. It helps that they can be made with whole-wheat flour. The Yakima Herald has two recipes: one small enough for a household and one big enough for a horde.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook