Why Telephone Companies Once Discouraged People From Chatting

Today phones have grown critical for making personal connections. The first phone companies probably wouldn’t have been thrilled.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to sweep across the world, putting billions in isolation, many people are scrambling to stay tethered to friends, family, and coworkers. More than 80 percent of people surveyed in the United States and United Kingdom report spending more time squinting at their phones and other screens, according to data published by the World Economic Forum. Those little screens have come to feel like a lifeline, offering a sense of community and a sliver of normalcy.

That’s not exactly new. Decades ago, Bell and AT&T ran ads exhorting people to “reach out and touch someone.” The ads promised that phone calls could collapse the physical and emotional distance between people. In one commercial from the late 1980s, a kid phoning his parents from college was able to picture his family’s routine—sister primping for a date, brother rushing in from soccer practice, dad rifling through the refrigerator just a few hours after dinner.

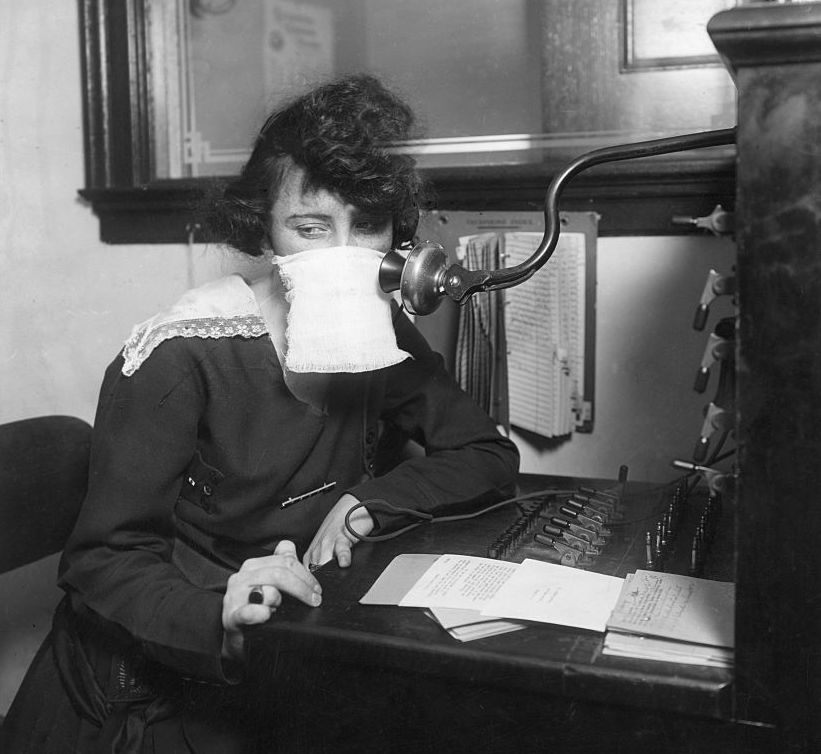

But, of course, it wasn’t always this way. The last time a pandemic of comparable scale stampeded around the world, in 1918, only around a third of American households had phones, The New York Times recently reported—and, obviously, those devices were much lower-fi. For decades, people with phones had been largely discouraged from using them for gabbing, ostensibly because some towns only had a few lines to serve everyone. Then, when the flu began to devastate communities, some phone companies begged people to keep their calls to a minimum, Fast Company reported. In October 1918, for instance, the Michigan State Telephone Company took out an ad in a Battle Creek newspaper, asking locals to “please restrict your use of the telephone to calls which are absolutely essential,” thus freeing up operators to attend to “the essential business of the community.” Similar messages went out in New Jersey and North Carolina, where an ad asked the public to “refrain from using the telephone except when necessary so that prompt service can be given to the sick.”

“The sociability function seems so obviously important today, and yet was ignored or resisted by the industry for almost the first half of its history,” writes Claude S. Fischer, a sociologist at the University of California, Berkeley, in a 1988 article in the journal Technology and Culture.

Atlas Obscura exchanged emails with Fischer, also author of America Calling: A Social History of the Telephone to 1940, about how phones have helped people connect—sometimes, to the frustration of the phone companies.

When the telephone first emerged as a consumer product, how was it marketed, and who was encouraged to buy it?

It was originally marketed to businesses as a business device—a much-improved telegraph. When the Bell company started marketing to households, it focused for 30-plus years on practical household management: Get the phone for your wife so that she can call the doctor, the grocer, the police, and you can call her when you’re coming home with company. That sort of thing.

How did that work out?

Household users did use it for these purposes, but almost from the start customers—notably women—used it for social purposes: To check in with others, to arrange social dates, and, frankly, to gossip. This was even clearer in rural areas, where the phones were a major social lifeline. The telephone industry for decades saw this as a misuse of the telephone, and even tried to suppress it.

What changed?

The shift was not the personal staying-connected use of the telephone, but the industry coming around to see these social uses as not a bug, but a feature. In the 1920s, the Bell companies switched from trying to repress chit-chat on the phones to marketing the phones as a great way to stay in touch with family and friends.

Now that we have so many other ways of staying in touch, what role does the phone play in times of crisis?

I see voice-to-voice communication today as part of a package of diverse and more flexible one-to-one communications, including email, texting, and the like. So people may, for example, text a few times a day, and arrange for a phone call on top. There is some evidence to suggest that the voice-to-voice remains the most intimate part of the communications package.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook