The Women Keeping Circassian Cuisine Alive in Jordan

A restaurant in Amman preserves the cooking traditions of a diaspora.

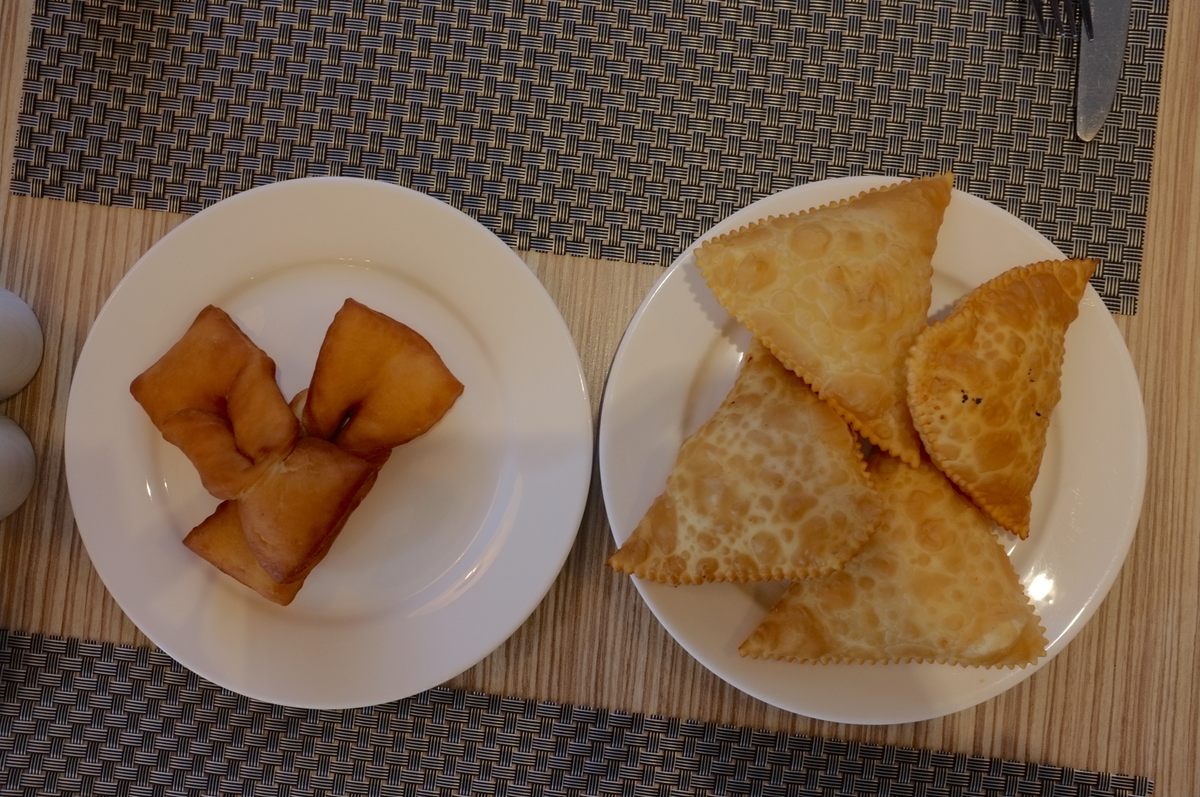

Every day, in a nondescript building in Amman, a cast of cooks, pastry makers, mothers, and grandmothers works to churn out take-away orders and meals for diners at Samawer. For many of the women, this is their first job. Young and old labor side by side to lay out, cut, and fold pastries called haleva, sprinkling their table with flour as they work. Others stuff kibbeh, a traditional Arabic dish, at different stations.

Samawer is known for its delicious meals, but the restaurant is performing a far more valuable service than simply feeding customers. It is one of the few restaurants in Jordan that specializes in Circassian cuisine, a style brought to the Middle East by a predominantly Muslim community that was exiled from the Caucasus in the late 1800s. It may look like the women at Samawer are simply gearing up for another routine breakfast service, but they’re also preserving a cuisine that many Circassians fear is dying out.

The restaurant is a part of the larger Circassian Charity Association in Jordan. Established in 1932, the association’s mission is to help the less fortunate within the community, while also hosting cultural activities. One year after the association created a women’s branch in 1970, Samawer opened its doors. Today, the restaurant employs more than 60 women from the local Circassian community.

“The older generations gave us the recipes and we carry them and pass them on, says Manal Lambza, a sous chef who has worked at Samawer for about 20 years. “We were born with this gift.” Lambza’s mother and grandmother taught her Circassian recipes like ships w pasta—patties of bulgur wheat and rice drenched in a rich, walnut gravy and spicy sauce—and she remembers watching them make the traditional food of their homeland when she was younger.

However, Lambza acknowledges that the Circassian language and food are “slowly fading.” Though there are no official figures, some estimates say less than 20 percent of Circassians still speak the language, and young adults are largely uninterested in learning to cook the hearty dishes they grew up eating as children.

Given the Circassians’ tragic history, it’s incredible that they’ve managed to maintain their traditions at all. Although originally from the northwest Caucasus, today, some 90 percent percent of Circassians live in diaspora. The forced migration dates back to the Russian-Circassian War. Sparked by Catherine the Great’s attempt to annex the Caucasus in 1763, the conflict dragged on until the defeat of the Circassians near modern-day Sochi in 1864.

After the Russian victory, Alexander II expelled Circassians to the Ottoman Empire—a brutal campaign in which the military razed villages and drove out hundreds of thousands of people. Many died in overcrowded ferries crossing the Black Sea or from disease in what some historians describe as “one of the least remembered genocides in world history.”

Today, the majority of Circassians live in modern-day Turkey. The second-largest population lives in Jordan, but there are smaller pockets scattered throughout Palestine, the United States, Egypt, Lebanon, the Balkans, and Germany.

As the Circassian population splintered, settled, and adapted to different parts of the world, so did their culinary traditions. In its homeland, authentic Circassian cuisine is meant to sustain and give energy in the cold climate of the Caucasus. Hearty and heavy on protein, it features warm stews and sausages made from sheep and goat organs. While Jordan-based Circassians have maintained many of these characteristics, they’ve had to make a few adjustments. When they first arrived in Jordan, for example, they were forced to make ships w pasta using bulgur wheat instead of the traditional corn because they could not find the latter.

At Samawer, chefs continue to use bulgur wheat and rice to make their ships w pasta. After forming the bulgur-and-rice base into squares, they drench the small cakes with ships, a gravy made from chicken stock, spices, butter, and walnuts. The last but most important aspect of the meal is the reddish-pink hot sauce, consisting of an onion-and-chili-pepper base with a hefty portion of garlic.

Yousef Bardouka, a young Circassian journalist, points to another example of a traditional food that transformed across borders. At Samawer, the haleva is a puffy and crispy pastry that gets filled with either potatoes or Circassian cheese, a salty cheese with a bit of a kick. However, “if you cross the river into Palestine, there are two Circassian towns that make their haleva in completely different ways,” he says.

Although he went to a Circassian school, like many young Circassians in Jordan, Bardouka says he is not heavily involved in the community. His father grew up in a town in the Golan Heights and would speak Circassian when he was younger. But his mother was part of a “generation that just completely dropped all elements of that culture,” he says.

Bardouka’s experience is a common one for many young Circassians in Jordan. By most standards, the Circassians’ assimilation and place in Jordanian society is a story of success. After pledging their loyalty to King Abdullah I, Circassians were instrumental in the founding of the Jordanian state in 1946. To this day, the royal guard is composed of Circassians.

Under the Jordanian constitution, Circassians enjoy the full rights of Jordanian citizenship. “We are not considered a minority by the government,” says Yenal Hatk, the vice president of the International Circassian Culture Academy.

Hatk points out that Circassians’ status might also partly be to blame for why their traditions are slowly fading in Jordan. “We were spoiled in one way or another, since we can open our own associations, our own clubs, our own schools, our own Circassian language courses, and do whatever we want,” he says.

By comparison, in Turkey, early 20th-century policies attempted to force Circassians and other minorities to give up their surnames and language in favor of Turkish. These challenges only served to solidify Circassian resistance and cultural identity. “That’s why they all managed to preserve the language and we’re losing it,” says Hatk.

Both Bardouk and Hatk are concerned about the future of Circassian language and food in Jordan. Behind Arabic, English is the second language of choice among most Jordanians, and many younger people no longer cook, instead relying on restaurants or delivery apps. “If we didn’t have Samawer, it would be lost slowly,” Hatk says of Circassian cuisine.

Within the walls of Samawer, however, the Circassian identity remains strong. Decorated in photographs and paintings of traditional Circassian figures, the restaurant still serves as a gathering place for the community. Tuleen Zoqash, a kitchen supervisor at the restaurant, says she is not worried about losing her culture’s culinary heritage. “We have existed here for a hundred years, maybe more and we still have our traditions, our food, our language,” she says. Tuleen adds that she has no doubt that Circassian food will endure in one form or another, even if that means simply passing down the recipes to a younger generation of workers at Samawer.

For Lambza, Samawer’s sous chef, serving and sharing traditional Circassian dishes is a way to keep the culture alive. She says a dish like ships w pasta is “something special that has to remain.” Comparing it to the Jordanian national dish of mansaf, she adds, “Ships w pasta is our traditional meal—our mansaf—what makes us special.”

Ships w Pasta

Recipe courtesy of Nesreen Qushha

For the Pasta

1/2 cup short-grain rice

1 cup bulgur wheat

3 cups water

Pinch of salt, to taste (but be sparse)

1. Combine the bulgur wheat, rice, salt, and water in a medium pot. Bring the water to a boil, then reduce it as you would when cooking rice.

2. Let the the bulgur wheat and rice simmer until both are soft, similar to the consistency of mashed potatoes. It should take about an hour to an hour and a half.

3. Mash everything together while it’s still in the pot with a balagh (a type of wooden spatula, but any spatula will work). Remove the mixture and place on a buttered tray. Pat and shape the mound into a large, even square, then cut into smaller squares about four inches from corner to corner. This should yield around six to eight squares.

For the Ships

1/2 cup brown flour

1 tablespoon butter

1 whole chicken

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon pepper

1 onion, chopped

⅔ cup walnuts

5 cloves garlic

1. Place the brown flour in a pan on low heat with the butter and stir until it turns a goldish-brown color. It should take around an hour on low heat.

2. Separate the chicken and wash it. Boil the chicken in a large pot with salt, pepper, and onion for around 45 minutes. Remove the chicken and strain the broth. Add the broth, along with the flour back into the same pot and slowly stir until it comes back up to a boil. Add the walnuts. Let this boil for about an hour, stirring occasionally.

3. Grind and crush the garlic with a mortar and pestle. Put two or three tablespoons of broth into the crushed garlic and then use it to rub down the chicken.

For the Hot Sauce (shepshidagha)

¼ cup vegetable oil

1 tablespoon butter

1 tablespoon paprika

½ teaspoon ground chili powder

1. Heat the oil and butter in a small pan. When the butter becomes translucent, turn off the heat and add the spices.

2. Stir for about a minute until it’s mixed and has become an almost translucent red color.

When everything is ready, plate the pasta alongside the chicken. Place the ships in a separate bowl to be used as a gravy. The hot sauce can either be drizzled on top of the ships or served on the side.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook