How Pie-Throwing Became a Comedy Standard

One film studio in Los Angeles pioneered the trope of flying pies.

One of the last places you might expect to find a commemorative plaque is on a concrete self-storage building in Los Angeles. But there, on 1712 Glendale Blvd., a plaque memorializes what was once a sprawling film lot known as Keystone Studios. The film company, now located in present-day Echo Park, was famed for its uproarious slapstick comedies—particularly those involving tossed pies.

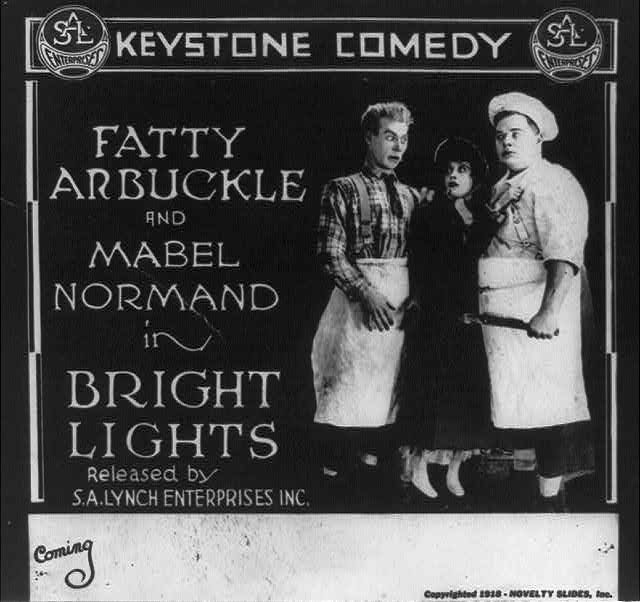

For over a century, flinging a pie into someone’s face has been a comedy trope, thanks in part to Keystone. Established in 1912 by director Mack Sennett, the studio was once touted as a comedy pioneer, and had a hand in making pie-throwing ubiquitous. Yet pie-tossing is a more common stunt in the popular imagination than it is in reality.

This phenomenon can be traced back before the earliest days of pre-1920s silent film. Tossing a pie into someone’s face for comedic effect first existed on the vaudeville circuit. The hilarity of seeing an elegant dessert hit an an actor, and watching them react with either anger or bewilderment, soon made its way to the screen. In 1913, Sennett’s muse Mabel Normand and Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle “launched the first such missile in a Keystone film,” notes The Oxford Companion to Food. Soon, the studio became known for pie-tossing shenanigans, and the high-flying desserts flew so freely that the studio needed its own bakery to make them.

The answer turned out to be right across the street. One Sarah Brener owned a variety store there, but she also supplied the studio with its pies. Sometimes, they were delicious. Charlie Chaplin said that Brener’s pies were the best in town (he once gave her one of his trademark canes as a memento, too). But often, they had to be specially formulated for films. The ones Keystone used were “a special ballistic version of the pie, with heavy-duty pastry and especially slurpy ‘custard.’” As pie fights in film grew more elaborate, Brener’s bakery was soon making nothing else.

Filmmakers preferred custard pies for flinging. They were appropriately messy and, without a top crust, likely less painful than a lattice-edged cherry pie would be to the face. In one biography of the silent film comedy star Buster Keaton, author Marion Mead recorded his pratfall-ready custard pie recipe. In it, two baked pie crusts were welded together with a solid foundation of flour and water. Then, they were filled with an inch of thick flour-and-water paste. If the pie was to be thrown at a blonde or a man in a light suit, a chocolate or strawberry garnish was added. For a man in a dark suit, the pie would be garnished with lots of whipped cream for the wreckage to show up well on camera. He also gave advice on how to throw it: like a Roman discus, for instance.

For a time, Keystone Studios was a powerful studio, launching stars like Charlie Chaplin to prominence. But by the time the 1920s rolled around, people had grown tired of the custard-pie shtick. It wasn’t long before comedies were being advertised on their pie-less merits: one ad trumpeted that “a custard pie and a pretty girl or two in a bathing suit do not make a comedy.” Pieing was so commonplace that Sennett had even developed rules for what characters could be taken down a notch with an ignominious pie to the face: mothers-in law, yes, mothers, no. (The humbling effect of a pie to the face has also made them a tool of political commentary.)

Widespread pie-throwing faded, but it didn’t die completely: Comedic films and animation alike have been peppered with pieing ever since, from Bugs Bunny to the Three Stooges. In 2015, The New York Times even reported that a “holy grail” of film history had been re-discovered: the second reel of the Laurel and Hardy 1927 short “The Battle of the Century”, where 3,000 pies sail through the air. It was supposed to be the pie fight to end all others, but in 1965 the film “The Great Race” promised viewers “the greatest pie fight in history.” Thousands of real pies were used, and after filming, the entire set stank of the rotting dessert.

Now, the Keystone building is a storage facility, and Brener’s bakery is long gone. But the studio’s influence lives on in film, in the occasional tossing of a pie, and on a plaque on the corner of the sole remaining building that reads: “This was the birthplace of the motion picture comedy.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook