The Beloved Japanese Novelist Who Became a Queer Manga Icon

Nobuko Yoshiya’s stories of frustrated, forbidden love helped establish a genre read by millions.

There is an ordinary building in Kamakura, Japan, that used to belong to an extraordinary woman. Nestled among elms and red maples, the house is an oasis, resembling a traditional teahouse in the Sukiya style characteristic of Kyoto’s 16th-century imperial villas. Now it is a memorial and museum dedicated to its former occupant, prolific Japanese novelist Nobuko Yoshiya.

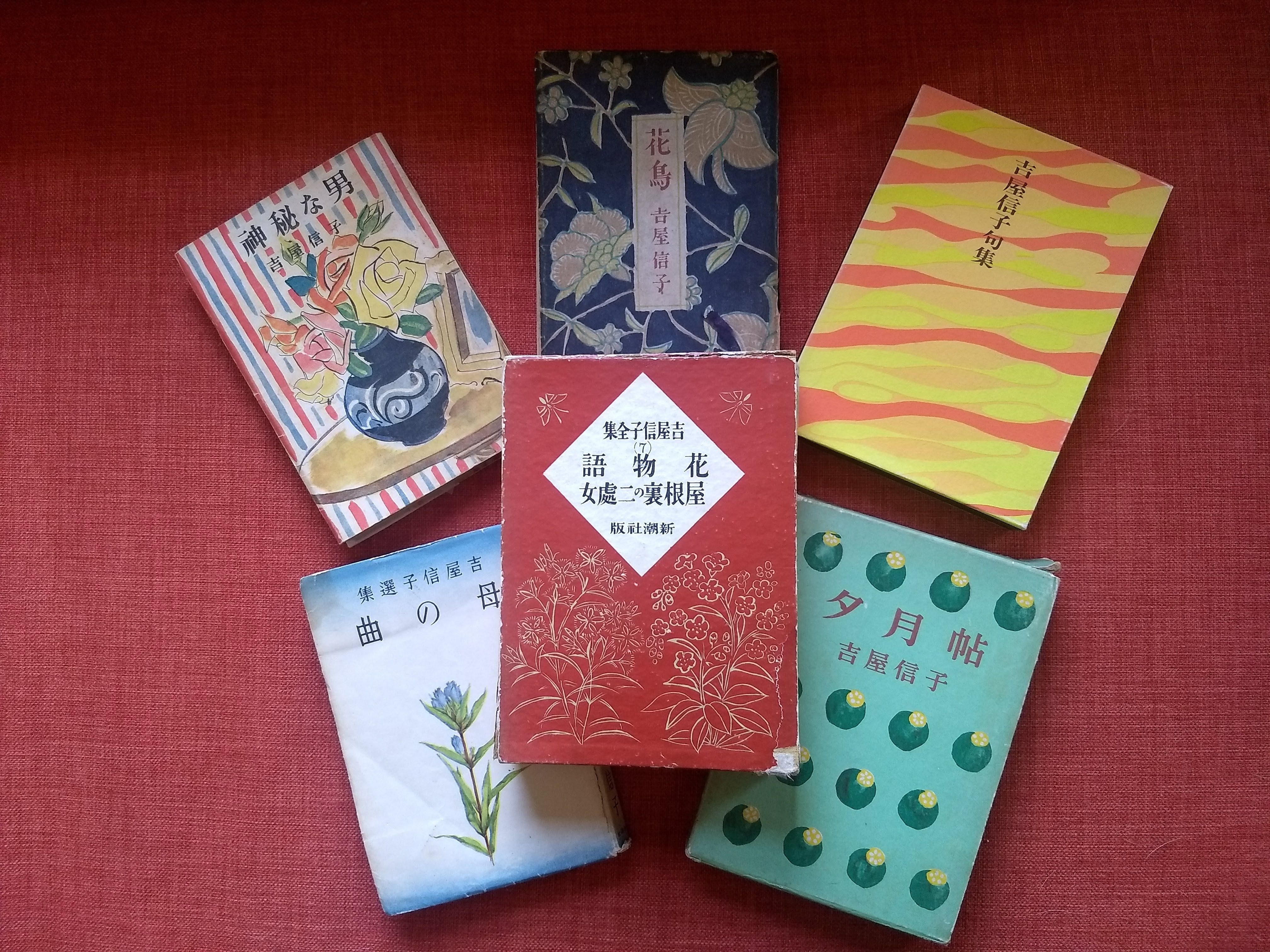

The Yoshiya Nobuko Memorial Museum is unusually hard to visit, but if you manage to make it inside, you will see a small arsenal of memorabilia from Yoshiya’s life: first-edition books, handwritten manuscripts, photos, and some of her original furniture. But the real allure is the house itself, preserved just as it was when Yoshiya died in 1973—including the study where she penned the novels that made her one of 20th-century Japan’s most successful writers.

Yoshiya never married; instead she lived with a female partner, Chiyo Monma, for 50 years. Despite a life lived against the grain, Yoshiya became one of Japan’s most beloved artists. She published feminist stories that focused on the strong emotional and romantic bonds between women—one with the notable title Danasama muyo (Husbands Are Useless). The impact of her novels is still being felt, far beyond the feminist and queer communities where she has become a particularly celebrated icon. Her writing laid the groundwork for shōjo manga, a genre of comics and graphic novels aimed toward teen girls that includes iconic titles such as Sailor Moon and Revolutionary Girl Utena—widely devoured by millions upon millions all over the world. “There is not a single woman alive who doesn’t know who Yoshiya Nobuko is,” declared a 1935 profile published in the magazine Hanashi.

Yoshiya was born in 1896 in Niigata, Japan, the only daughter in a family of five children—an upbringing that had an impact on her approach to gender roles, and her resentment of the male domination of society. In 1915, Yoshiya moved to Tokyo, where she resided for the rest of her life. She began attending meetings of Seitō, Japan’s pioneering feminist magazine, where she met other modern female writers attempting to carve out lives not beholden to men. With the support of this community, she cut her hair into an unconventionally short bob and began to wear men’s clothing.

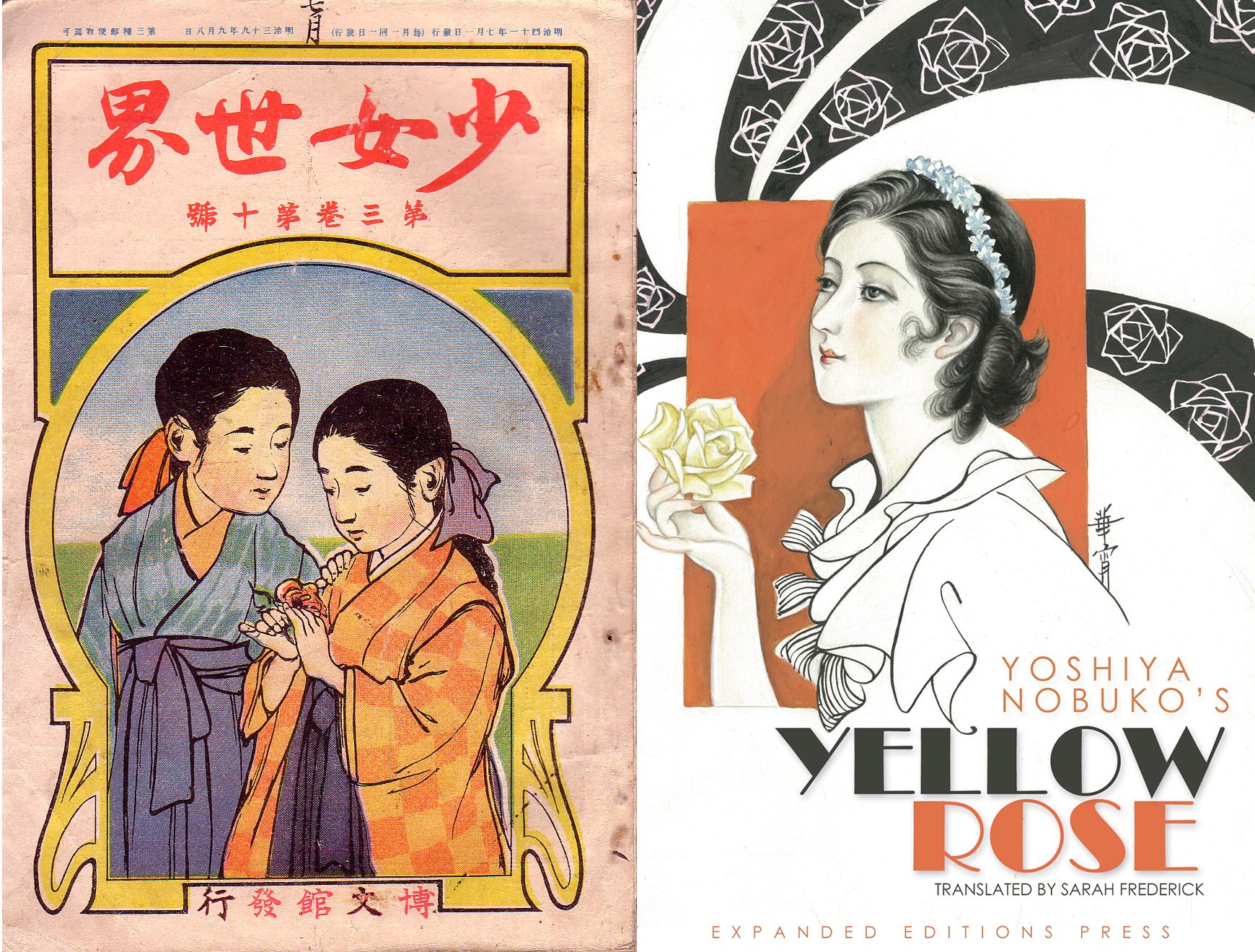

Just a year later, Yoshiya published a 52-story collection called Hana monogatari. Translated into English as Flower Tales, the collection details intense emotional relationships between girls—and introduced many of the motifs and symbols that define modern shōjo manga, such as the boarding school dormitory setting, imagery involving Western flowers, and a dreamily wistful style of writing. Yoshiya used flowers, most often roses, to symbolize the emotional intensity of these girls’ relationships. Each story was paired with an illustration by the famed artist and doll creator Jun’ichi Nakahara, who drew schoolgirls with the huge, bubbly eyes so characteristic of manga and anime today. Most of the Flower Tales concern unrequited crushes or longing among women, often for another student or a teacher.

These stories soared in popularity and cemented Yoshiya’s place among the canon of popular Japanese writers. According to Sarah Frederick, a professor of Japanese literature at Boston University, Yoshiya’s stories can be read two ways: as queer (though they hold back from anything more shockingly sexual than a kiss) or as purely, if intensely, platonic.

In 1919, shortly after Flower Tales, Yoshiya wrote one of her best-known—and most scrutinized—stories, ”Yaneura no nishojo” (“Two Virgins in the Attic”). Many critics read it as quasi-autobiographical, as it follows two students, Akiko and Tamaki, who feel like outcasts in their dormitory. They spend all their time in a triangular attic, where they develop a romantic longing. They spy on each other in the bathroom and smell each other’s scent of “lily magnolia”—all culminating in a kiss. Urban Japanese architecture has a notable lack of attics, yet they commonly appear in modern-day shōjos—a lineage almost directly traceable to Yoshiya.

Many manga scholars consider “Two Virgins in the Attic” to be the first prototype of yuri manga, the modern extension of shōjo that is more explicitly focused on lesbian romantic and sexual relationships, according to Hiromi Tsuchiya-Dollase, a professor of Japanese at Vassar College. Though yuri is now considered a genre in its own right, some of the most popular shōjo mangas of all time, including Sailor Moon, have subplots that veer into yuri.

Though male homosexuality had a long history in Japanese culture, literature, and art, at the time the country had no conception at all of sexual relationships between two women, Tsuchiya-Dollase says. In the Edo period, which spanned most of the 17th through 19th centuries, it was considered normal and often idealized for men to engage in love affairs with both women and men. These same-sex relationships existed under a code of ethics called nanshoku, wherein older men could pursue younger men who had not yet undergone coming-of-age ceremonies.

But at the turn of the 20th century, Japanese culture clearly understood the specific concept of an S relationship, or a passionate friendship between two girls (the “S” stands for “sister”). In the 1910s and 1920s, S relationships were everywhere in literature written for schoolgirls, where these intensely emotional relationships were seen as training for eventual marriage with a man. Though many modern readers classify Yoshiya’s work as lesbian literature, the term “lesbian”—or in Japan, rezubian—only came into popular use after Yoshiya’s death. Instead, her work belongs squarely in the acceptable realm of S relationships—though it was deeply imbued with what we now recognize as queerness.

These inclusive if shrouded conceptions of same-sex desire changed when Sigmund Freud began publishing works on the aberration of homosexuality in the early 1910s, according to Tsuchiya-Dollase. It suddenly became dangerous for women to hold hands in public, or even exchange letters. In 1911, two high school girls died together in a high-profile “love suicide” under the understanding that their love could not continue in the post-graduation world, writes Peichen Wu in the collection Women’s Sexualities and Masculinities in a Globalizing Asia.

This shift coincided with Yoshiya’s ascendance to commercial success. After “Two Virgins in the Attic,” she stopped writing about schoolgirls and turned to housewives. Her stories lost almost all explicit queerness, and instead focused on unhappy marriages in which a wife, after learning of her husband’s affair, takes solace in the arms of a close female friend. But whenever something resembling a queer relationship begins to form, one character will end it in a typical “bury your gays” trope—usually by dying or becoming a nun.

Yoshiya’s queerness may have been veiled in her work, but her private life was no secret. Early in her 20s, Yoshiya met Monma, who was working as a math teacher at the time. The two soon became inseparable, and in classic lesbian style, moved in together within a year of meeting each other. After Monma’s job sent her away for 10 months, Yoshiya mailed her beloved a rather practical proposal.

1. We will build a small house for the two of us.

2. I will become the head of household and officially adopt you.

3. We will ask a friend to serve as a go-between, and hold a wedding reception.

Same-sex marriage was not, and still is not, legal in Japan, so adoption was the only legal recourse that would allow two unrelated women to co-own property or make medical decisions together. Monma accepted, and the two moved into a small house in Tokyo. By 1928, Yoshiya had amassed enough royalties to own five homes in Japan, one of which would become her future museum.

During Yoshiya’s life, Tokyo hosted other female writers with known romantic relationships with other women. In the early 20th century, prominent Japanese-Russian translator Yoshiko Yuasa became one of the first female Japanese writers to go public with her relationship with a woman, and later in life explicitly identified as a lesbian. But Yoshiya stands out as someone who both wrote about same-sex love and friendship, and also lived with a female partner for her entire life, according to Hiromi Tsuchiya-Dollase, a professor of Japanese at Vassar College. Japanese society didn’t seem to mind—or at least they managed to ignore it. During World War II, the government even commissioned Yoshiya to report on the war.

The first iterations of illustrated shōjo comics appeared in magazines not long after the war. Despite their intended audience of teenage girls, they were largely created by male artists who either needed the money or saw shōjo manga as a training ground for shōnen manga, the genre aimed at boys. Either way, these men didn’t know what their teen readers wanted. “So they read Yoshiya’s stories and copied her works,” Tsuchiya-Dollase says. She cites Osamu Tezuka’s popular Astro Boy manga, for example, as an example of an early manga that drew inspiration from Yoshiya’s themes of sentiment and melodrama. Similar to the plight of many of the orphaned heroines in Yoshiya’s work, Astro Boy is discarded by his father and creator, who had made him to fill the void of his dead son. Tsuchiya-Dollase believes this theme, of longing to be loved by absent parents, could derivey from Yoshiya’s work.

Women did not begin working as shōjo manga artists until the 1960s, often making their debuts—as Yoshiyo had as a young writer—by entering competitions in magazines. These new female artists began writing more complex and authentic stories of girlhood, which sold better among their target audience. By the 1970s, which some see as the golden age of shōjo manga, women artists outnumbered men. By the early 1990s, artists began expanding the genre to include young warriors (Red River and Sailor Moon) and ecologically inspired science fiction (Please Save My Earth and Moon Child). Steered by this new female vanguard, shōjo plots drifted away from heterosexual romance and toward self-fulfillment.

In the late 1990s, shōjo manga more directly inspired by Yoshiya—primarily focusing on the love between girls—experienced a major revival when writer Oyuki Konno published Maria Is Watching, which Tsuchiya-Dollase calls a direct descendant of Flower Tales. Like Yoshiya’s early work, Maria takes place in a dormitory, teems with melodrama, and tells the stories of strong emotional relationships between young girls. The manga also involves Yoshiya’s beloved European roses and distinctly floral dialogue.

In turn, Maria inspired a new burst of shōjo manga written by women that focuses on strong female bonds. Notable examples include Magic Knight Rayearth and Nana as well as Revolutionary Girl Utena, set in a magical academy featuring queer characters who transgress gender roles and so, so many roses—in tornadoes, graveyards, and even a garden that hosts a very queer dance.

Yoshiya’s work should be considered feminist for her women-centered narratives, according to Michiko Suzuki, a professor of Japanese and comparative literature at UC Davis. “Yoshiya created new ways for girls and women to imagine themselves,” she says. “They uphold the ideal of female sisterhood above all else.”

Early in her career, Yoshiya wrote a letter to her Monma threatening war on male writers who she saw as chauvinist pigs, who could care less about the meaningful relationships girls could have with each other. “Almost to the point of endorsing obscenity, they push on girls the idea that they should be flirting with men,” she wrote, coming to what she saw as a perfectly logical conclusion. “I will do battle with them face-to-face shouting ‘begone you demons’ and exorcise them from our midst.” The sensitive students, powerful magic-wielders, and ecological warriors in shōjo manga today are keeping up that fight.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook