The Atlas Obscura Guide to

North Iceland’s Untamed Coast

Any travel enthusiast would be hard-pressed to open any social media channel and not see photos of Iceland, with its jaw-dropping peaks, natural hot springs, pure glaciers, northern lights and snow-covered landscapes. But the island nation’s appeal goes well beyond the well-worn paths of Reykjavik, the Golden Circle and the southern region's countryside. Travel to the untamed north along the Arctic Coast Way to discover otherworldly beauty—sans crowds—around every bend.

1. Dettifoss

Iceland is famous for its spectacular waterfalls, many of which are beautiful and serene places for contemplation. Dettifoss is not one of them. Having earned the superlative of “most powerful waterfall in Europe” because of its massive flow rate (3,059,112 U.S. gallons per minute), standing near this unfettered display of power will give you a healthy respect for the fury of nature.

From Route 1 (commonly known as Iceland’s Ring Road), visitors can easily access Dettifoss by driving north on the paved Route 862. However, if traveling from the north (from Route 85 via the Ásbyrgi canyon area), be prepared to brave some rather rough gravel roads, which may or may not be closed depending on the weather. (There’s a reason why four-wheel-drive rental cars come in handy in this rugged nation.) If the roads are clear, pack your rain gear and hiking boots. Even on a sunny day, mist from the flow of glacial water can be visible from up to a mile away and any wind change might leave you soaked.

The 330-foot-wide falls are fed by the river Jökulsá, which means “glacier river” in Icelandic, a reference to the Vatnajökull glacier (recipient of another superlative: one of Europe's largest). Be careful as you approach and stick to designated pathways since even they can be rendered slippery in the mist. The falls’ water tends to be a dingy grayish color, thanks to the water picking up the black volcanic silt from the river bottom. Movie buffs might recognize Dettifoss from its star turn as another planet in the opening scene for the 2012 movie Prometheus.

Dettifoss, Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland

2. Krafla Caldera

If you want to continue the alien theme, the Krafla caldera—a 6-mile-long active volcano zone that sits squarely on the border between the Eurasian and American tectonic plates—is a must-visit. Drive up a winding mountain road until clusters of red geodesic domes come into view. That’s the power plant harnessing the area’s geothermal energy, and it means you’re close.

Krafla is part of a large volcanic system and one of Iceland’s most explosive volcanoes. The most recent eruptions occurred frequently between 1975 and 1984, and the eerie landscape bears witness to what churns beneath the surface.

From the parking area, take a hike along a well-worn path and you’ll notice the geology of the area change before your eyes. Lava fields, puddles of bubbling mud, evaporating clouds of sulfur-scented steam, solidified magma splashes and horizontal striations of various colors from layers of lava make the Krafla caldera look like a scene straight from Mars. It’s such a close match, there are plans for the area to host the Mars Society’s European Mars Analog Research Station (Euro-MARS) to observe humans living in space-like conditions.

Krafla Caldera, Northeast, Iceland

3. Vogafjós’ Cowshed Cafe

Many farm families in Iceland boast a closely guarded family recipe for "geyser rye bread," baked with some combination of rye flour, spring water, sugar and seasonings. The ingredients are mixed, formed into loaves and baked beneath the ground, using the natural, geothermal heat for which Iceland is famous. At this pastoral cafe, on the eastern shores of Lake Mývatn, the geyser bread—which is baked underground for 24 hours—is a star menu attraction, along with raw smoked lamb, pan-fried trout and cured arctic char pulled from the lake.

The cow farm, which is currently home to 16 stout bovines, has been in the same family for more than 120 years. In 2005, the family added 26 guest rooms, and later, they converted their small food takeaway counter into a full-fledged restaurant. Guests who want to get close to the eatery’s agrarian roots can watch the cows being milked or sit outside overlooking the pasture. For a special treat, the kitchen blends the geyser bread into their singular delicacy, geyser bread ice cream.

Vogafjós Farm, 660 Mývatn, Iceland

4. Mývatn Nature Baths

The north’s lesser-known answer to the southwest’s Blue Lagoon lies in the hot mineral springs next to Lake Mývatn. Unlike the touristic attraction to the south, this picturesque pool is naturally fed by geothermal water drawn from a fissure nearly 2,500 meters deep. Rich in silicates, minerals and beneficial microorganisms, the water is purported to have healing properties. That chemical composition, plus a starting temperature of 130 degrees Celsius, also makes it an inhospitable environment for any undesirable bacteria or vegetation.

Guests shower in gender-specific locker rooms before wading into the outdoor lagoon, which contains nearly a million gallons of steaming blue water with temperatures between 36 and 40 degrees Celsius. If you’ve had the forethought to order a drink inside, a friendly lifeguard will deliver it to you at the edge of the pool. The complex also includes an outdoor hot tub, two steam saunas, and views of the surrounding volcanic landscape. While the pool structures themselves are man-made, the water is completely natural and the complex represents a good example of Icelandic hot spring culture.

Jarðbaðshólar, 660 Mývatn, Iceland

5. Goðafoss

Just about every waterfall in Iceland has a story, and Goðafoss, which means “waterfall of the gods,” is no exception. According to the Icelandic sagas, in the year 1000, Þorgeir Ljósvetningagoði, the region’s Viking leader, threw his Norse idols and instruments into the waterfall to signify the end of paganism and the start of Christianity. The nearby church, Þorgeirskirkja at Ljósavatn (Icelandic for Þorgeir's Church), was built in 2000 to commemorate a millennium of Iceland being a Christian nation.

The powerful falls stretch across a curve of nearly 100 feet, with water from the river Skjálfandafljót tumbling over massive boulders and down 39 feet before continuing on its way. The lush valley surrounding it is primarily covered with shallow lava topsoil, so the delicate flora includes dwarf shrubs, moss and lichen, which grow on the rocks surrounding and separating the falls. Goðafoss is located right on the Ring Road, (named such because it follows the country’s perimeter), so visitors can choose to park on either side. Either way, an easy walk gets you close to the majestic display from the top. For those who wish to view the falls from below, walk to the east side and hike down the rocky path for a new perspective.

Goðafoss, Iceland

6. Húsavík Whale Museum

At just 2,300 residents, Húsavík is one of the densest towns lining Iceland’s sparsely populated Northeast coast. The country’s self-described “whale-watching capital” is home to the Húsavík Whale Museum. A former livestock slaughterhouse offers more than 15,000-square-feet of exhibition space filled with 11 whale skeletons, including an 82-foot-long blue whale found beached at Ásbúðir, a farm in Northern Iceland.

Standing in front of the only blue whale skeleton in Iceland gives you an appreciation for the size of the creatures—the largest ever to have lived, with calls that can travel hundreds of miles underwater. Other fully assembled skeletons include a Sowerby’s beaked whale, minke whale, long-finned pilot whale, sperm whale, and a narwhal, dubbed the “unicorn of the sea” because of its single horn-like tusk.

Other engaging exhibits include a “touch and see” box with artifacts—like a baleen whale skull bone, part of a shark tail, vertebrae of a northern bottlenose whale, and a humpback whale’s baleen plates—to handle up close. Undulating lighting and underwater noises turn the museum into a place to both learn about and meditate on these giants of the deep.

Hafnarstétt 1, Húsavík, Iceland

7. Hákarl

In centuries past, food was often prized more for its ability to sustain than its ability to delight the taste buds. There’s perhaps no better example than hákarl, the pungent—some might say putrid—fermented shark the Vikings created in Iceland’s early days. The meat of Greenland sharks, the world’s longest-living vertebrates at 300–500 years, is poisonous when eaten fresh. But Viking ingenuity discovered that burying pieces of the shark meat underground for several weeks could neutralize the toxins. Next, the slabs of meat were hung to age further. The bite-size chunks of white meat have a urine-like smell, thanks to the ammonia in the uric acid naturally present in the shark’s flesh.

While hákarl is now produced primarily to be eaten during the annual midwinter Þorrablót festival, the gastronomically adventurous (or foolhardy, depending on your view of eating what some have described as “urine-soaked cheese”) can find this historical food in high-end grocery stores, like the Hagkaup in Akureyri. When asked if he liked the Icelandic delicacy, the best a store clerk could say was, “It’s a very particular taste.” To sample it like Icelanders do, plan to wash the hákarl down with a shot of Brennivín, the traditional unsweetened, carraway-flavored schnapps.

Hagkaup Grocery, Grenivellir 26, Akureyri, Iceland

8. Hvoll Regional Museum

This Dalvík museum’s star is an exhibit dedicated to the town’s larger-than-life resident. Jóhann Pétursson was dubbed “The Giant,” because at 7’8” he was known as the tallest man alive during his lifetime (1913–84). When you visit, snap a photo next to an outdoor display showing Pétursson’s impressive height, sit in a larger-than-life bench that would have fit him, and wonder at archival photos documenting his time as a vaudeville performer around Europe and later as the “Viking Giant” in the United States’ Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus.

The rest of the museum's collection is filled with various tools, furnishings, arts, and crafts, which provide insight into Dalvík's history, culture, and community. The natural history collection contains a large number of taxidermied Icelandic birds and mammals, including a toothy polar bear.

Karls-Rauðatorg, 620 Dalvík, Iceland

9. Tvistur Horse Rental

Saddle up an Icelandic horse at this family-run stable near Dalvík, and you’ll take part in a proud national tradition. The unique breed of smallish horses came to Iceland with the first Viking settlers from Norway about 1,100 years ago. Because of the land’s isolation and stringent laws restricting equine imports, Icelandic horses are among the purest horse breeds in the world. Riders will notice that these friendly and playful beasts have two gaits in addition to the typical walk, trot, and canter/gallop common to other breeds. Experience the tölt, a four-beat prance that’s fun even for beginners. More advanced riders will want to strive for the skeið, or “flying pace,” that can reach up to 30 miles per hour in which all four hooves are suspended off the ground.

At this stable just south of Dalvík, 40 of the Sveinbjarnarson family’s horses are housed in a former mink farm. Stable staff guide guests of all experience levels on rides atop the sure-footed horses — choose between a walk along the Svarfaðardalsá river or a trek up into the mountains overlooking the stables. On a clear day, you’ll be able to survey the surrounding landscape, including the Kaldbakur peak, which remains snow-capped even in the summer.

Hringsholt, 620 Dalvík, Iceland

10. Bjórböðin Beer Spa

If drinking beer gives you a flushed glow, imagine what taking a bath in a vat of suds will do. At Iceland’s first beer spa, opened in 2017, singles or couples can soak in 700-liter tubs made from Kambala wood from Ghana. Each bath is filled with a secret blend of antioxidant-packed hops, vitamin B-rich brewer’s yeast, warm mountain spring water and essential oils to soothe the body and nourish the skin during the timed 25-minute session. Guests over 20 (Iceland’s legal drinking age) can sip from an all-you-can-drink tap of golden lager brewed by the adjacent Bruggsmiðjan Kaldi, Iceland’s first microbrewery, opened in 2006.

Once soaking time is up, guests pad upstairs to a dark gabled room full of individual daybeds where an attendant drapes you with a cozy blanket while the yeast goes to work on your skin. Visitors who want more time can spring for a session in one of two outdoor hot tubs overlooking Eyjafjörður, one of Iceland’s longest fjords. Even the locker room showers feature beer-infused shower gel and shampoo.

Ægisgata 31, 621 Árskógssandur, Iceland

11. Gestastofa Sútarans

Fine leather and wool products are some of Iceland’s most popular souvenirs, but for something more unique, visit the Tannery Visitor Center, one of a small number of tanneries in the world (and the only one in Europe) producing fish leather. The business originally opened in 1961, specializing in lambskins. Forward-thinking local entrepreneurs responded to an economic downturn in the early 1990s with a solution to leverage the seafood skins which would otherwise be discarded.

Now, leather artisans work with local fishermen to cure salmon, perch, wolffish and cod skins, which are treated with vibrant natural dyes in every imaginable color, including an array of metallics. After curing for at least a month, sales reps claim the finished skins are as much as five times more durable than cow leather. The Center offers both custom and off-the-rack handbags and belts, as well as less expected items like bowties and jewelry made out of sustainable fish leather.

Borgarmýri 5, Sauðárkrókur, Iceland

12. Seal Colony at Hvítserkur Bay

Most wildlife spotting on Iceland’s northern coast—such as whale watching and puffin sighting—requires time spent on a boat. To see one of the region’s largest seal colonies, however, you can stay on the shore, if you know where to look. Make your way to the Ósar Hostel, 26 miles from Hvammstangi (the closest town), and be prepared to rough it a bit. When you turn off of Route 1, you’ll need to brave more than 15 miles of bumpy gravel roads. Bring a pair of binoculars and take an easy walk through a sheep pasture down to the coast.

Once you’re by the water, you should be rewarded with a view of a large seal colony frolicking in the frigid surf and sunning themselves on the black sand beach. Visitors are most likely to see the critically endangered harbour seals that lounge here year-round, but occasionally guests might spot grey seals, or even travelers not native to Iceland, including bearded seals, ringed seals, hooded seals, and harp seals. An annual “great seal count” happens here every summer, and in recent years an average of 760 seals have been spotted in this area, though they sometimes disappear for a short time in search of a fresh meal.

Vatnsnesvegur, Iceland

13. Hvítserkur

When you approach the 49-foot tall basalt rock stack jutting out of Húnaflói Bay on the Vatnsnes Peninsula, you’ll probably see something in its M-like shape. Some say they see a rhino drinking from the chilly water, others see a dinosaur and still others see a troll, which gives the monolith its nickname “The Troll of Northwest Iceland.” Legend has it that the troll, Hvítserkur, came down from his mountain across the bay to destroy the church bells that annoyed him. When the rising sun shone, however, it turned him to stone. Science tells us that the stack was formed by erosion over millennia, with waves carving holes into the stone to create the leg-like base. Because the rock is constantly battered by waves, some concerned locals added a bit of concrete to reinforce it.

In Icelandic, the name Hvítserkur translates to “white shirt,” a nod to the color of the bird droppings that cover the rock. It serves as a nesting ground for seabirds like seagulls, shag and fulmar. Confident and sure-footed hikers may brave the steep dirt path to the shore to get an up-close look, depending on the tide. Otherwise, you’ll have to be content with an aerial view from the lookout point above.

Vatnsnesvegur, Iceland

This post is promoted in partnership with Icelandair. Learn more about Iceland and 20+ destinations in Europe.

Queens

New York City's most diverse borough is also its most rewarding.

San Diego

Southern California's second city holds plenty of sparkling secrets.

Savannah

Find surprises around every corner in a U.S. city that embraces history like no other.

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Places to Eat and Drink in Oaxaca

Oaxaca, the mountainous state in Mexico’s south, is celebrated as the country’s “cradle of diversity.” Home to 16 Indigenous ethnic groups from Mixtecs to Triques to Zapotecs, it also boasts the country’s greatest biodiversity, counting 522 edible herbs, over 30 native agave varieties distilled by some 600 mezcal-producing facilities, 35 landraces (unique cultivars) of corn, and some two-dozen native species of chiles and beans. Oaxaca de Juárez, the state’s colonial capital, is drawing record numbers of visitors these days for its cobblestoned streets and the arty graffiti. But the main draw is Oaxaca’s status as the culinary epicenter of Mexico for its dozens of mole varieties, an encyclopedia of corn masa-based antojitos—memelas, tetelas, totopos, tlayudas, tamales—and a baroque layering of colonial-Spanish and pre-Hispanic Indigenous foodways. Local chefs understand that to be culinary authority here one must be part botanist and part anthropologist—roles which they embrace with great relish. Among the welcome recent developments to the restaurant scene has been the great rise of female chefs, as well as a new interest in cooking from the state’s different regions in addition to the complex colonial flavors of the Valles Centrales surrounding the capital. Whether you’re after unusual moles from the rugged Mixteca region, breads made exclusively from Oaxacan wheat, or a country lunch featuring edible insects, our guide has you covered. From a cult street taco stand to a Michelin-starred chef resurrecting forgotten dishes, here are the culinary highs to hit.

A Gastro Obscura Guide to Family-Friendly Dining in San Diego

Sponsored by San Diego Tourism

In San Diego, a city on the sea just over the border from the coastal state of Baja California, the freshness of the food leaps off the plate, thanks to chefs who are constantly finding new ways to turn local produce and seafood into something delectable. The city’s history, heritage, and proximity to Mexico—combined with the fresh, simple flavors of California cuisine—create a cross-border culinary identity known as Cali-Baja. It’s not just a fusion, but a lifestyle rooted in variety and simplicity. While San Diego has a long and celebrated tradition of excellent Mexican food—from street tacos to aguachile—that’s just the beginning. The city’s diverse neighborhoods each bring something unique to the table: hand-pulled noodles in Convoy District, beachside burgers in Ocean Beach, artisan pasta in Little Italy, and seafood-forward small plates in La Jolla. The commitment to bold flavor and local ingredients is unmistakable. And thanks to year-round sunshine and a laid-back beach culture, great food is easy to find and even easier to enjoy. This diversity of cuisine, paired with an adventurous, open-hearted spirit, makes America’s Finest City a standout destination for curious eaters and families alike.

The Explorer’s Guide to Outdoor Wonders In Maryland

Sponsored by Visit Maryland

With wild horses, a small elk called a “sika,” a massive population of bald eagles, and the once-endangered fox squirrel, the state of Maryland is home to a thrilling variety of wildlife. Across diverse ecosystems like swamps, cliffs, mountains, and sandy beaches, the state springs alive during spring and summer with the sounds of birds, mammals, amphibians, and reptiles that the state has been careful to protect. Perfect for outdoor enthusiasts, these parks, preserves, and protected areas across Maryland offer visitors a chance to encounter fauna they may have never even known existed.

The Secret Lives of Cities: Ljubljana

How many times can a city be called a “hidden gem” before it stops being hidden? Judging by the enthusiastic throngs wandering its cobbled Baroque streets in summer, Slovenia’s capital has certainly been discovered, but perhaps by the wiser tourists. Though it is popular it is never overcrowded, and each visitor who falls for its charms (and they inevitably do) feels as though they’ve stumbled upon a secret treasure. Perhaps this lingering sense of discovery comes from its tricky-to-pronounce name (Loo-blee-ah-nah) or the fact that Slovenia only gained independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, making it feel newly accessible to many travelers. But this very quality is part of its appeal—Ljubljana is a city full of surprises. It’s unexpectedly elegant and prosperous (historically the most developed of the former Yugoslav capitals), remarkably easy to visit , impressively green (a former European Green Capital with the highest percentage of pedestrianized streets in Europe), surprisingly well-connected, and effortlessly cool. With a quarter of its 300,000-odd inhabitants being students, Ljubljana has a vibrant, youthful energy combined with refined Central European charm. Though often grouped with “Eastern Europe,” all of Slovenia actually lies west of Vienna, which was historically its greatest influence, having been part of the Habsburg Empire for centuries. The city center is compact, highly walkable, and photogenic, with minimal Socialist-era architecture disrupting its Old World atmosphere—unlike sister cities such as Belgrade. And then there’s its stunning backdrop: a 30-minute drive north, the snow-capped Alps rise majestically above the skyline. Spend just a few hours in Ljubljana, and it will come as no surprise that its name translates to “beloved.”

From Cigar Boom to Culinary Gem: 10 Essential Spots in Ybor City

Sponsored by VISIT TAMPA BAY

In Ybor City, the past and present blend like the perfect café Cubano—rich, bold, and impossible to resist. Situated just northeast of downtown Tampa, Florida, the enclave was founded when Cuban cigar entrepreneur Vincente Martinez-Ybor opened a factory here in the 1880s. That one business move created a boom for cigars (at its height, Ybor City had more than 200 cigar factories), prompting an explosion of lodging, restaurants, shops and nightclubs. Today, it’s still a haven for vibrant cultural touchpoints that blend its Cuban roots with Floridian, Spanish, Italian and global influences from farther-flung locations. On its charming streets, guests will find Cuban eateries ranging from traditional to creative, and cigar shops (and even a working factory) that retains the spirit of its past. From picadillo to hand-rolled cigars, Ybor City has plenty of treasures to offer. A word to the wise: Come hungry for discovery.

The Explorer’s Guide to Wyoming’s Captivating History

Sponsored by Travel Wyoming

From legendary outlaw hideouts and prehistoric fossil beds, to a centuries-old Native American rock formation and a critical landmark along the Oregon Trail, Wyoming is packed with storied sites worth seeing. Here’s 10 fascinating stops to get you started.

A Nature Lover’s Guide to Sarasota: 9 Wild & Tranquil Spots

Sponsored by Visit Sarasota County

With its endangered Florida scrub jays, athletic bobcats, fields of colorful wildflowers, and eerie mangrove tunnels, southwest Florida’s Sarasota County is far from one note. While it offers the requisite Sunshine State landscapes of pristine beaches and lapping waves, there’s so much more for nature lovers to see and experience. With 725 square miles—including 35 miles of beachfront overlooking the glittering Gulf of Mexico—Sarasota County has varied landscapes that support all manner of wildlife. Whether you’re looking for a low-key stroll beneath moss-draped trees, the rush of seeing hundreds of alligators converging in one place, or an exploratory horseback ride, this extraordinary area has you covered. Here, we’ve rounded up nine can’t-miss Sarasota stops, so get ready for the ultimate outdoor lovers’ excursion. Trust us: Sarasota County hits all of the high notes.

California’s Unbelievable Landscapes: A Guide to Nature’s Masterpieces

Sponsored by Visit California

California is a land of dramatic landscapes. It has mountains, volcanoes, sweeping deserts and seashore galore; its natural splendor even extends below the surface of the earth, to cavernous caves and man-made underground gardens. Many of its geological and biological wonders will make you feel like you’re on another planet, or like you’ve been transported to a storybook where trees speak, shrink, or live forever. Whether you’re eager to explore volcanic history, surround yourself with walls of glistening ferns, or summit mountains to see twisting trees and desert views, in California, the most unbelievable landscapes are just around the corner.

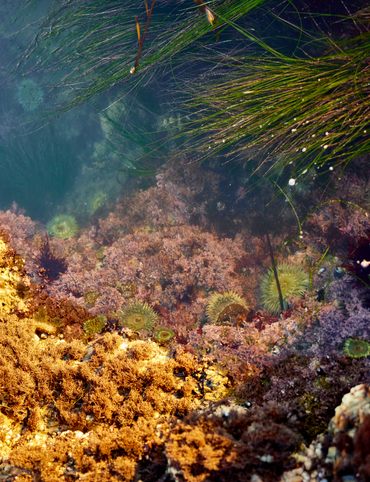

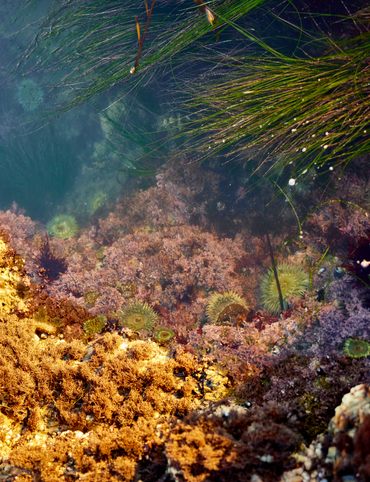

The Ultimate California Guide to Tide Pools and Coastal Marine Life

Sponsored by Visit California

California’s long coast is beloved by surfers, sure, but it’s also a hotbed for another sort of sunny activity: tide pool exploration. At low tide along California’s shoreline, pools of tiny living wonders appear – home to sea stars, urchins, spiny lobsters, slugs, shells and flowing bits of algae. We’ve rounded up some of the best tide pools in the state, to inspire the budding marine biologist in all of us. Know Before You Go Before you begin your tide pool adventure, there are a few things you should know. 1. First, check the tide schedule before you set off for the beach, as most of these tide pools are only visible at low tide. (Fall and Winter are usually the best seasons for this sort of exploration, as the tides are lower.) 2. In order to preserve the wild world of nature that exists inside each tide pool, you should never remove any animals from their habitats; some state parks even forbid touching the animals inside the tide pools, so follow the local rules at every stop along the way.

Explore California on Foot: Nature’s Year-Round Playground

Sponsored by Visit California

For those of us who live in colder climates, California can seem a legitimate dream: sunny beaches, temperate mountain vistas, and awe-inspiring desert landscape. In every season, the Golden State is rife with opportunities for strolling, hiking, and rambling through its diverse climates and thrilling geographies. You can walk breezy beaches and see a waterfall that crashes directly into the sea, climb the country’s highest sand dunes, explore a glistening green canyon, or even go subterranean. Whatever you choose, we’ve collected 10 great ways to see the state on foot.

Mardi Gras 9 Ways: Parades, Cajun Music, And Courirs Across Louisiana

Sponsored by Explore Louisiana

There’s more to Mardi Gras than the raucous parade on Bourbon Street. Travel outside New Orleans and you’ll find a diverse array of celebrations ranging from the traditional Courir de Mardi Gras to a sustainable parade with no plastic (and no barriers). Each is unique, and most are more family-friendly than NOLA’s well-known Bacchanal. We’ve compiled some ideas for celebrating the holiday while dancing, while supporting a good cause -- and even while getting up close to some swamp creatures. Get ready to see what Louisiana has to offer.

The Explorer’s Guide to Winter in Germany

Sponsored by The German National Tourist Office and Lufthansa

In Germany, the winter holidays are a gift that never stops giving. From Christmas markets to skiing adventures in the Alps, the country’s main seasonal attractions are well known, but the cooler months of December to March also offer much more off the beaten path. Hidden snowscapes, markets, and manors straight out of the Brothers Grimm books promise a unique turn to the wintertide. Here are some of the best, lesser-known places for outdoor fun and indoor warm-ups across the country. And if you’re ready to book your next trip, Lufthansa operates direct flights from 20 U.S. cities to Germany, making it easier than ever to plan the perfect German winter adventure.

Ancient California: A Journey Through Time and Prehistoric Places

Sponsored by Visit California

What makes California an absolute playground for prehistoric artifacts? Is it because so much of the state is undeveloped desert? Is it because the entire state was once a warm, shallow sea roughly 500 million years ago? Or is it because California was home to some of the earliest human settlements in North America? If you answered “all of the above,” you’re correct! Here in California, the distant past has a habit of poking its nose into the present in weird and wonderful ways—the stops on this prehistoric itinerary will show you why.

The Wildest West: Explore California’s Ghost Towns and Gold Fever Legacy

Sponsored by Visit California

Once gold was discovered in the deserts of the American West, people from all over the world converged there in the middle of the 1800s. It took some time, however, for law enforcement and civil society to catch up—hence the period of American history now dubbed “the Wild West.” While the gold is gone and the desert towns of California’s interior are now calm, law-abiding communities, that historical spirit lives on in the towns, architecture, and museums along this daring itinerary. This is the Wild West like you’ve never seen it before.

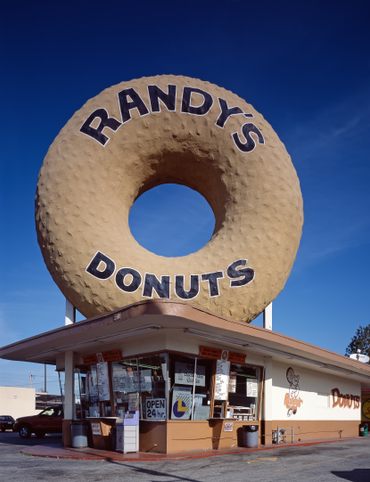

Sweet California: A Culinary Guide to Tasty Treats Across the State

Sponsored by Visit California

Many different cultures have called California home over the years, from the Chinese to the Dutch to the Japanese, and what they all had in common was an insatiable sweet tooth. This delicious itinerary explores this legacy in the form of fortune cookies, sodas, donuts, cupcakes, and more. Finish your dinner—you’re definitely going to want what California’s got for dessert!

Sea of Wonders: An Itinerary Through California’s Stunning Shoreline

Sponsored by Visit California

With shoreline from end to end, it’s no wonder California has some of the wildest marine excursions, architecture, and animal life in the country. Grab your surfboard, pack your binoculars, and bring a towel—there’s a world of wonder packed in this itinerary along California’s curious coastline.

10 Places to Taste Catalonia’s Gastronomic Treasures

Sponsored by Catalunya

When it comes to food, Catalans do it better. Despite having a population of just over eight million—smaller than the state of Virginia—the region is home to 54 Michelin-starred restaurants, 12 designated wine regions, and nine official wine routes. Catalonia also has more than four million acres of farmland, with many of its 54,000 farms adhering to organic practices. But to understand Catalan food culture, you must look beyond the statistics: to the secret herb formulas for making vermouth and the family recipes passed down through generations; the ancient rice paddies, olive mills, and an entire tradition built around a humble vegetable, the calçot. You’ll need to look, too, to the people of Catalonia, whose deep-rooted love of all things gastronòmica means that every moment of the day, week, or year is a potential culinary celebration. Here’s where and how to experience 10 of the best Catalan food traditions on your next visit to the region.

Atlas Obscura’s Guide to Palm Springs

Sponsored by Visit Palm Springs

A paradise in the desert, Palm Springs is a city of contrasts. Kitsch sidles up to luxury, natural beauty serves as the backdrop to architectural marvels, and when you soak in an ancient hot spring, you might catch the latest TV star doing the same. One of the biggest contrasts is this: while Palm Springs is a beloved vacation spot, it still holds lesser-known wonders waiting to be discovered. Looking for something you’ll find nowhere else? Head down a nondescript residential street and find an army of enormous pink robots. If you’ve got a case of the shoppies, there’s an antique mall to explore and an artist community full of galleries and studios. If you want to learn about the area’s human history, look no further than the Agua Caliente Cultural Plaza (and take a soak in the spring-fed waters while you’re at it). Natural areas allow you to explore canyons and waterfalls; restaurants and bars let you feel like you’re flying on a midcentury airline or in the audience of a vintage game show; heck, you can even get up close and personal with a windmill farm. And if you’d rather just see all of it from above, you can ride the world’s largest rotating tram car from the desert floor up to the San Jacinto Mountains. The question isn’t “Does Palm Springs have something for me?” but “How am I going to fit it all in?” Start with this list.

Atlas Obscura’s Guide to the 10 Most Mystifying Places in Illinois

Sponsored by The Illinois Office of Tourism

A presidential tomb that carries endless drama. A thriving prehistoric society that vanished without a trace. A haunted fun house with a wine cellar apparition.When you think of Illinois, you probably don't think of mysterious mounds, creepy clowns, and a park filled with dragons and wizards. We figure it’s time we changed that. Jump in and join us for a whirling tour through some of Illinois’s most inexplicable, unexpected, and unsuspecting sites.

10 Fascinating Sites That Bring Idaho History to Life

Sponsored by Visit Idaho

From its remote log cabins and carbonated natural springs to the tale of how the Nez Perce people came to be, Idaho is a land brimming with curious wonder. There’s so much to see and do in this northwestern state, whether it’s taking a drive along a 135-mile-long scenic byway dedicated to Sacajawea—the only woman to accompany Lewis and Clark on their historic expedition—or discovering the history of the Basque people at a museum that sits smack dab in the middle of the largest Basque community in the US. We’ve rounded up 10 captivating sites that help bring the incredible story of Idaho to life—get ready for the ultimate road trip.

North Carolina's Paranormal Places, Scary Stories, & Local Haunts

Sponsored by Visit North Carolina

With its wooded mountains, industrial history, and wide, sweeping bluffs, North Carolina is a surprisingly haunted state, an ideal site for lingering ghosts and bumps in the night. While many visitors flock to the esse Quam Videri State for pulled pork barbecue, pristine beaches, and towering mountains, it’s also rich in hauntings, and perfect for a ghost tour. In the Appalachian mountains, you’ll find a Vanderbilt mansion with spooky hidden passageways; in Cape Lookout, you can take a ferry to a long-forgotten island village, home only to ruins and specters. And beneath the waters of the state’s largest man-made lake, you may just find a monster to rival that of Loch Ness. Below, we’ve collected the state’s best, spookiest, most haunted sites home to hidden histories.

Exploring Missouri’s Legends: Unveiling the Stories Behind the State’s Iconic Figures

Sponsored by Visit Missouri

A world-famous animator. A Wild West outlaw. The patron saint of prairie literature. And an iconic, mustachioed novelist. These are just a few famous residents of Missouri’s history. Across the state, homes and museums and gardens have been preserved and dedicated to these beloved Missourians. You can tour the childhood homes of Walt Disney and Mark Twain, visit the homestead where Laura Ingalls Wilder wrote the Little House books, and visit a penitentiary where world heavyweight boxing champion Sonny Liston learned the sport. The “Show-Me” state is full of history everywhere you look, much of it tied to the lives of the people who lived, worked, and made art here.

These Restaurants Are Dishing Out Alabama’s Most Distinctive Food

Sponsored by Sweet Home Alabama

You could easily spend a month eating through Alabama’s restaurants, from fish shacks to fine dining havens, and barely scratch the surface. Thanks to its position on the gulf coast and its long growing season, the state is brimming with delicious cuisines, both traditional and forward-thinking. One day you may be digging into perfectly-fried fish in a refurbished camp along the coast, and the next you might be drinking a glass of local beer paired with a locavore salad set atop a white tablecloth. From its signature barbecue sauce to its gulf shrimp to the unique creation that is West Indies Salad, Alabama is an eater’s paradise. Here are some of the restaurants dishing up the state’s signature meals.

A Gastro Obscura Guide to Los Cabos

Sponsored by Los Cabos Tourism

The innovative mix of Mexican, Mediterranean and Asian-inspired flavors and cooking techniques has created a delectable fusion, “Baja-Med.” Food is the conduit to creating community here, among local farmers, fishermen and restaurant entrepreneurs; and with visitors who are open to experiencing the richness of the land and culture via exquisite tastes, sensory immersion, and creative presentation.

9 Watery Wonders on Florida’s Gulf Coast

Sponsored by VISIT FLORIDA

With all its tidal pools, mangrove islands, and estuaries, Florida’s Gulf Coast shoreline is one of the most dynamic in the country. Throw into the mix almost a thousand natural springs, and Florida truly is a place with as much to explore both above water as below. This ten-stop itinerary is by no means exhaustive. The mermaid shows, cave-diving, underwater museums, mangrove-kayaking, and wildlife-watching opportunities presented here still only scratch the surface – and the depths - of the myriad activities possible along this wondrous coastline.

Discover the Surprising and Hidden History of Monterey County

Sponsored by See Monterey

Monterey County, nestled on California’s stunning Pacific Coast, is a treasure trove of lush landscapes and breathtaking ocean views. But beyond its natural beauty lies a rich tapestry of human history waiting to be explored. Hike a National Historic Trail while learning about the area's Indigenous communities; watch a thrilling race at the storied Laguna Seca Raceway; and get lunch at a restaurant that epitomizes the Oaxacan presence in Monterey. This itinerary will take you to museums and reserves across the county and its thousands of years of human history.

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to Eating Your Way Through Charlotte

Sponsored by Charlotte Regional Visitors Authority

In a city like Charlotte, it’s easy to stick to the new and the known. But dig deeper and you’ll find that the Queen City isn’t just a spot for barbeque and southern fare, but a melting pot with immigrants who dreamed of displaying the best of their culture on dinner plates and front porches. You’ll find that a taste of Italy is just as close as the corner store; you can experience the magic of dining inside an historic craftsman bungalow in one of Charlotte’s iconic neighborhoods. Hear from owners who have spent their lives here, cultivating menus that keep patrons coming back week after week for decades. Though driven by new growth, the charm of old Charlotte still exists in the corners of the city, and the flavors of global cuisine are sprinkled throughout, just waiting to be discovered. Let this guide be your culinary inspiration to go and try it for yourself.

Talimena Scenic Byway: 6 Essential Stops for Your Arkansas Road Trip

Sponsored by Arkansas Tourism

The Talimena National Byway travels roughly 15 miles through western Arkansas to the Oklahoma line, meandering through the stunning Ouachita National Forest, Arkansas’ second-highest peak at Rich Mountain, and into historic Queen Wilhelmina State Park. Dig into small-town history, savor a juicy burger at a remote country store, and marvel at scenic overlooks and waterfalls along the way.

9 Amazing Arkansas Adventures Along the Scenic 7 Byway

Sponsored by Arkansas Tourism

Spanning roughly 300 miles through the state of Arkansas, the Scenic 7 Byway is a road-tripper’s mecca. Dense pine woodlands in the south give way to the verdant Arkansas River valley, reaching the lush Ozark and Ouachita mountains. Dig for crystals, sample the state pie, explore natural formations, and soak in The Natural State’s rich culture and history as you stretch your legs at these worthwhile stops.

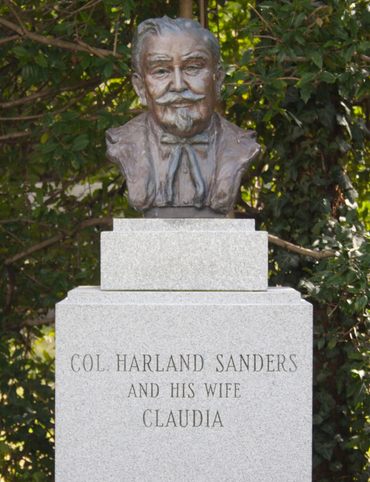

The Explorer's Guide to Highway 36: The Way of American Genius

Sponsored by Visit Missouri

Spanning the state of Missouri, from St. Joseph to Hannibal, Highway 36 is full of intriguing stops packed with incredible stories of innovation. Known as “The Way of American Genius,” the route highlights inventions and individuals who left a lasting mark. From the starting point of the Pony Express and the bakery that introduced sliced bread to magical towns that sparked inspiration for creative geniuses Walt Disney and Mark Twain, these spots along Missouri’s Highway 36 will leave any traveler dreaming of the next big thing.

A Behind-the-Scenes Guide to DC’s Art and Music

Sponsored by Washington.org

For Washingtonians, there’s “Washington”—the well-known stretch of historic sites and cultural institutions that draws visitors from around the country to the nation’s capital—and then there’s the city they call home. That’s D.C., a patchwork of vibrant and diverse neighborhoods, each with their own rich history and distinct culture—alive with go-go music, locally made spirits, community conversations, and indie art. These are just a few of the landmarks locals know in Northwest D.C.—from the cycling path that leads to an artists’ community to a risqué mural that signals some of the best blues in the District.

9 Places Near Las Vegas For a Different Kind of Tailgate

Sponsored by Travel Nevada

While Las Vegas is known for its glitzy neon signs, buzzing clubs and nightlife, and over-the-top casinos, the region itself is also home to some wondrous bars and eateries that lie well beyond the crowded Strip. This Super Bowl season, it’s time to engage in a new type of tailgate. From a stripmall world of tiki to a downhome diner where daily specials are part of the allure, here are 9 places that offer a culinary escape from the bright lights of Nevada’s most iconic city.

10 Places to See Amazing Art on Florida's Gulf Coast

Sponsored by Visit St. Pete/Clearwater

From whimsical private home tours to funky creative hubs, hands-on glass-blowing galleries, and lots more, there’s no shortage of alluring art attractions in St. Pete/Clearwater.

8 Reasons Why You Should Visit the Bradenton Area

Sponsored by Bradenton Area Convention and Visitors Bureau

Hugging the Manatee River, just south of Tampa Bay, Bradenton is a central Florida destination brimming with soul. At the annual Downtown Bradenton Public Market, peruse the goods of nearly 100 vendors and pick up beach-themed art, local coffee, gifts, jewelry, clothes, and much more. Equally diverse is one of the Bradenton area’s hippest neighborhoods, the vibrant Village of the Arts, home to nearly 20 funky art galleries, plus top-notch restaurants serving southern soul food and more. A sustainability-minded vintage shop and an authentic Italian café known for its fresh-from-the-garden pesto and daily baked breads are worthy draws, as is the Carnegie Library, with its packed corridors of historic county papers and artifacts. History buffs will also love to travel back in time at the Manatee Village Historical Park, with over 15 distinctive historical and replica sites, including a steam engine, general store, and blacksmith shop. And the sacred Native American burial grounds and countless encounters with Florida’s diverse wildlife inspires awe at the 365-acre Emerson Point Preserve. With its impressive variety of sites to see, places to eat, and things to do, Bradenton’s reputation as the Friendly City is equally welcoming. Here are 10 destinations to get you started on your next visit to the Bradenton area.

A Music Lover’s Guide to New Orleans

Sponsored by New Orleans & Company

Perched at the mouth of the Mississippi River, New Orleans has been a crossroads of cultures since its first indigenous inhabitants. Just over a century ago, the interplay of West African, European, and Caribbean influences in the Crescent City forged the signature sound of American jazz. Today, thanks to the culture bearers who have passed this musical tradition down over generations, you can still hear what those jazz geniuses were cooking up. What’s more, music infuses every part of life in New Orleans, from football games to funeral processions, parades to public parks. Here are 10 places to immerse yourself in the rich landscape of New Orleans’ musical scene.

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to Sipping Wine in Catalonia

Sponsored by Catalan Tourist Board

Looking for a surprising and scenic backdrop to sip on some extraordinary wines? Enter: Catalonia. A less obvious choice than, say, Bordeaux or Tuscany, Catalonia has no fewer than 300 wineries spread across 12 designated regions (or denominaciones de origen) in an area the size of Maryland. That’s a lot of grapes per square mile. Nine wine routes have been specially developed to show off the best of each one. Here are 10 experiences in the DO Penedès Wine Route, the DOQ Priorat Wine Route, the DO Alella Wine Route, the DO Empordà Wine Route and the DO Pla de Bages Wine Route to explore some of the most quaffable wines in the region.

9 Hidden Wonders in the Heart of Kansas City

Sponsored by Visit KC

To soak in the soul of Kansas City, you can sink your teeth into succulent brisket burnt-ends, bask in the melodies of live jazz at one of the city’s legendary venues, or catch a thrilling Chiefs game– and that's just the beginning of uncovering its rich tapestry. But there’s another side to KC—under-the radar destinations that are packed with wonder and intrigue. Peel back a layer, and Kansas City reveals unexplored magic: from a holy finger housed in a world-class museum and a 70-year-old lunch counter that still keeps lines out the door, to the historic social epicenter of Black jazz and an original private-collection Winston Churchill work of art – and there’s even more waiting to be explored. Here are nine hidden wonders of Kansas City.

10 Unexpected Delights of Vermont's Arts and Culture Scene

Sponsored by Vermont Department of Tourism and Marketing

With its high peaks and verdant valleys, Vermont is meant for exploration. Go beyond its natural beauty and you’ll find the state’s creative side, in both historically notable institutions and the contemporary arts community quietly making wondrous work. This itinerary will take you from cherished museums to off-the-beaten-path cultural gems including a library and opera house that straddles the U.S.-Canada border, a collection of antiques that contains an 892-ton steamboat, and a Gothic church-turned-rock club. Through river towns and over mountaintops, you’ll see magnificent steel sculptures rise from rolling hayfields and expansive murals covering main streets. You’ll meet puppeteers and painters, dog lovers, and dreamers. So buckle up and wind your way to these 10 exciting art destinations that are sure to inspire your own creativity.

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to Eating Through Maine

Sponsored by Maine Office of Tourism

While lobsters, blueberries, and whoopie pies certainly come to mind when thinking about the edible wonders of Maine, they’re also just the tip of the iceberg. Stick to the headliners and you’ll miss out on some other uniquely Maine food and drink. Within the 3,500 miles of tidal coast, the quaint mountain towns, and nature-adjacent cities that make up the Pine Tree State, you’ll encounter off-the-beaten-path culinary settings including the only food truck park in New England, a Deer Isle sculpture park that sells jams and jellies, and a James Beard-nominated eatery operating out of a 100-year old dining car. You’ll meet one-of-a-kind food figures like the speech pathologist running a flour mill out of a former jailhouse, or an Amish deli run by a military-man-turned-chef out of a log cabin without electricity. And you’ll taste some of Maine’s lesser-lauded flavors, from seaweed jerky to maple syrup brandy and blueberry port. So do enjoy Maine’s revered blueberries, seafood, and baked goods. Just remember the myriad culinary curiosities also waiting in the wing for you.

The Gastro Obscura Guide to Asheville Area Eats

Sponsored by Explore Asheville

Asheville might be the best food city you haven’t visited. This mountain town in Western North Carolina has long been a destination for foodies–a self-proclaimed Foodtopia®–and beer lovers: thanks to the region’s rich culinary history, and the town’s quirky, creative soul, it has become a hotbed of culinary experimentation, top-notch microbreweries, and community-focused, farm-to-table food. Even better – it comes with a breathtaking mountain backdrop. Here are 10 places to explore some of the best food and drink in the region.

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to St. Pete/Clearwater

Sponsored by Visit St. Pete/Clearwater

A destination with thriving cultural cities, charming small towns, nature parks, and some of the top-ranked beaches in the country, St. Pete/Clearwater is the best of Florida all in one neat, welcoming peninsula. So welcoming, in fact, that the region is seeing a steady population growth that is fueling something of a cultural renaissance. The newcomers it’s attracting—in tandem with the locals who’ve been here all along—are building an eclectic community, with some unexpectedly tasty results. Out-of-towners arrive with creative business concepts like tropical Art Deco cafés or a pizzeria run by an acrobatic pizzaiolo. The local crowd reimagines long-standing structures, from a historic theater-turned-Roaring ‘20s nightclub to an ATM-turned-taco stand. And far-flung emigres weave strands of their home countries into the global tapestry that is St. Pete/Clearwater, from a British tea parlor to a French-Vietnamese restaurant serving two chefs’ childhood favorites. So by all means, come for the lively nightlife, the pristine beaches, and the wondrous museums. Just don’t forget to bring your appetite, too. Welcome to St. Pete/Clearwater.

9 Hidden Wonders in Eastern Colorado

Sponsored by Visit Colorado

Colorado is known for its towering mountains adorned with wildflowers, waterfalls, and endless hiking trails; however, some of its best kept secrets lie on the eastern half of the state. This adventure will take you to the furthest reaches of Colorado’s beautiful prairie and up into the pristine foothills of the Wet Mountains - all places seldom visited and teeming with intrigue. The locations below have been hand-picked for their uniqueness and ability to inspire you to journey through time via some of Colorado’s most obscure and interesting haunts found on the high plains.

7 Places to Experience Big Wonder in Texas

Sponsored by Travel Texas

Texas is a wide-ranging, diverse, and expansive state. Even the barbecue you’ll get from one county to another is never the same, and the music sounds a little different in the depths of West Texas than it does in the panhandle. Texas is huge—you’ve probably heard that—and it offers attractions to match its size. We’ve rounded up our favorite places to see the heights and depths of Texas—from its tallest peaks to its heftiest steaks. Put on your ten-gallon hat and your tallest boots, and set out on a road trip that’ll help you get a sense of just how big the state really is.

8 Out-There Art Destinations in Texas

Sponsored by Travel Texas

A surplus of space always means a surplus of creative possibility. Texas, with its never-ending skies, wide deserts, and even bigger imaginations, takes this idea to thrilling conclusions. If you’re interested in planning an art-focused road trip, you won’t find a better destination than Texas, where one day you’ll be browsing an obsessive collection of outsider art, and the next day you’ll be walking through a hidden alley covered in umbrellas or beneath a neon skyscape. Here are eight of the most exciting art destinations in the state to inspire your mind and thrill your eyes.

6 Ways To See Texas Below the Surface

Sponsored by Travel Texas

One of the most thrilling ways to explore a new place is to go underground. Spelunking, or cave exploration, offers a completely different view: instead of seeing what’s been built up, you see what hides beneath. Texas, with its rich and varied geological history, has a wide collection of subterranean attractions. Say goodbye to above-ground reality for a while, and plan a trip exploring below the surface. Here’s how.

9 Places to Dive Into Fresh Texas Waters

Sponsored by Travel Texas

Texas summers don’t mess around: it gets hot around these parts. Which is why swimming holes are so important to the state’s residents—and, luckily, its geography. Around the state, you’ll find natural springs, waterfalls, lakes, and even mermaids to welcome you into fresh waters. Whether you’re planning a swimming-themed road trip or need a spot to cool off the next time you’re in the panhandle, these are our favorite places to splash around in Texas.

7 Ways to Explore Music (and History) in Texas

Sponsored by Travel Texas

Visit any honky tonk around the state and you’ll immediately know: Texans love their music. This is a state rich with musical history and musical culture, from the roots of country music to libraries dedicated to the preservation of historic gospel records. Below are some of the most interesting ways to experience music and sound in the state, whether you’re a country music lover or simply a traveler with curious ears.

8 Ways to Discover Texas’ Rich History

Sponsored by Travel Texas

As the largest state in the contiguous U.S., Texas also holds a vast amount of the country’s history. While we all remember the Alamo, there’s also a trove of geological, cultural, and even gastronomic history among Texas’ wide skies and vast deserts. Here are some of the most exciting spots to learn about the state’s past, while enjoying its present.

The Explorer’s Guide to the Northern Territory, Australia

Sponsored by Tourism Northern Territory

The Northern Territory is home to rich Aboriginal culture that spans back around 60,000 years. The history, culture, and stories of the dozens of Aboriginal nations that make up the area are an intrinsic part of every experience you will have here.Located in the central north of Australia, the Northern Territory is three times the size of California, but has a population of only 250,000. It’s a land with a deep and sacred connection to its history, colorful deserts, and lush tropical rainforests. Visit the Northern Territory to experience the ancient wisdom of Aboriginal astronomers, sample unique bush tucker, and see creatures found nowhere else in the world.

The Explorer's Guide to U Street Corridor

Sponsored by Washington.org

The U Street Corridor is an epicenter of art and African American heritage in Washington, DC. Once known as “Black Broadway,” U Street was the center of Black culture in America. (It’s where Duke Ellington was born!) Though the neighborhood struggled in the years following the 1968 riots, it’s as vibrant as ever today. Start your day on U Street at a mural honoring Black Americans from Harriet Tubman to Dave Chapelle, and end at a beloved Ethiopian restaurant where you might be lucky enough to catch some live music and dancing. Along the way you’ll grab a drink, uncover forgotten history, and stand inside theaters where everyone from Ella Fitzgerald to Nirvana have performed.

Gastro Obscura Guide to Southern Eats

Sponsored by Partners of Travel South

The American South is a mecca of delectable, comforting, and enduring cuisines from an array of cultures. Ranging from Creole to soul, and from Appalachian to Zimbabwean, our multi-state guide offers a unique tasting adventure that you won’t find anywhere else in the world. This itinerary blends some of the most iconic, lesser-known food stops across Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, and North Carolina into one unforgettably tasty road trip.

Only In Delaware

Sponsored by Visit Delaware

Delaware may not be the largest state in the country (in fact, it’s the second-smallest, and could squeeze into the next biggest state, Connecticut, two times comfortably). It’s not the most metropolitan, either (in fact, its capital city, Dover, is one of the least populated capital cities in the country). Delaware is, however, the oldest state in the country. The rich history therein, along with the natural beauty of the Blue Hen State and the unique characters who have called it home, make it a true hidden gem. From opulent family gardens to cannonball-riddled homes to fascinating defense structures, this itinerary will guide you through some of the state’s most extraordinary attractions. Beside outdoor activities like kayaking, horseback-riding, and fishing, there’s also historic homes, museums, and art installations of unthinkable scale. Sometimes, it’s true what they say—the best things do come in small packages. Welcome to Delaware.

The Secret History & Hidden Wonders of Charlotte, North Carolina

Sponsored by Charlotte Regional Visitors Authority

At the heart of the south, Charlotte is a booming city full of new life. Cranes have dotted the skyline for more than a decade as it has become the most populous city in North Carolina. There is so much to see in Charlotte, from a rose garden hidden just outside the city center to a retro video rental store with over 30,000 titles. What many newcomers don’t know is Charlotte’s deep-rooted history that dates back to before the colonies became the United States. This list of 10 destinations will only scratch the surface of the many special places to visit in the Queen City.

Exploring Colorado's Historic Hot Springs Loop

Sponsored by Visit Colorado

Nestled in the imposing Rocky Mountains of Colorado and the gorgeous high-alpine valleys, the Historic Hot Springs Loop is a treasure trove of geothermal hot spring resorts and destinations, offering visitors a chance to unwind and recharge in pristine natural mineral waters. The loop, which stretches from Glenwood Springs to Ouray, is home to an array of distinctive hot spring resorts, each with their own unique history, atmosphere, and therapeutic properties. From the luxurious spa-like feel of Glenwood Hot Springs with the world’s largest geothermal pool, to the rustic charm of Ouray Hot Springs with soothing vapor caves, there's something for every type of hot spring enthusiast.

These 8 Arizona Ghost Towns Will Transport You to the Wild West

Sponsored by Visit Arizona

In the desert of Arizona, a string of ghost towns have been preserved and refurbished to give visitors a glimpse into the history of miners and the businesses who served them during the boom times of the turn of the century. Whether you want to pan for gold, discover junk art, or stay a night in a mining engineer’s cabin, these ghost towns will transport you into Arizona’s Wild West past.

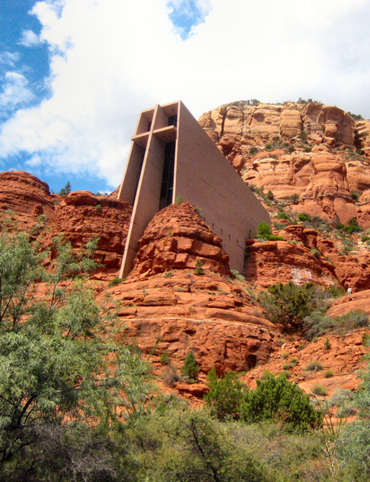

A Guide to Arizona’s Most Striking Natural Wonders

Sponsored by Visit Arizona

Arizona has some of the most beautiful and surprising landscapes the American West has to offer. The geography of this northeastern stretch of the Sonoran desert can be incredibly dramatic. And while we’ve all heard of—or seen—the majesty of the Grand Canyon, there are a number of lesser-known natural wonders that will take you off the beaten path in this gorgeous state.

The Explorer's Guide to Hudson Valley, New York

Sponsored by Defender

Just a short trip north of New York City, the Hudson Valley is great for both day trips and road trips. Atlas Obscura co-founder Dylan Thuras is a local resident, and loves the natural wonders, as well as the incredible culture and history found in the region. This itinerary combines his favorite spots into one stunning road trip. Start your adventure at a living antique aviation museum near the historic town of Red Hook, and end with dinner at a Victorian resort. Along the way, you’ll make pit stops at towering waterfalls, a giant kaleidoscope, and incredible views of the beautiful Hudson Valley.

Discover the Endless Beauty of the Pine Tree State

Sponsored by The Maine Office of Tourism

When people think of Maine, it’s often the rugged beauty of the coast that comes to mind: sunsets over craggy shorelines, lighthouses surrounded by towering pines, and lobster boats dotting the bay. But whether you’re angling for a hike, paddle, or simply a long drive through the backcountry, there’s no shortage of spectacular natural features throughout all of Maine’s 16 counties. This itinerary will take you from secluded coves along Maine’s coastline to the highest peaks in the state, alongside thundering waterfalls, mystifying geology, and myriad wildlife. Welcome to Maine—act natural.

Travel to New Heights Around the Pine Tree State

Sponsored by The Maine Office of Tourism

There’s already plenty to see and do in Maine with your feet firmly planted on the ground. But what if you could change your vantage point and get above it all? This itinerary will send you into the clouds, atop the state’s highest peaks, and through endless skies on planes, chairlifts, and hot air balloons where you’ll be able to take in Maine’s grandeur with nothing but crisp, clean, mountain air in the way.

8 Historical Must-Sees in Granbury, Texas

Sponsored by Visit Granbury

Granbury, Texas is 70 miles southwest of Dallas but a world away from the Big D’s big-city vibe. Founded in 1860, Granbury started as a town square with a log cabin courthouse. Today, this charming town of around 10,000 is the seat of Hood County and home to the first town square in Texas to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A poster child for restoration projects all over America, Granbury boasts a lively arts and dining scene; plenty of green space; and a lake with a sandy beach used for splashing, sunning, and kayaking along the shore. Then there’s the lore and legend that the locals swear by, Texas tales which may be tall or true. The town’s history is one of its great advantages, and peering through that lens is the best way to truly see Granbury.

7 Creative Ways to Take in San Antonio’s Culture

Sponsored by Visit San Antonio

If you’re planning a trip to San Antonio, all signs will point you to the Riverwalk, the most-visited tourist destination in the whole state. And while the area offers countless bars, restaurants, and shops, the city is host to a wide array of cultural gems, waiting in plain sight. Whether it’s visiting gorgeous missions, touring sculpture gardens, or immersing yourself in African-American history, San Antonio contains fascinating excursions that will brighten up any trip.

Eat Across the Blue Ridge Parkway

In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt so enjoyed a ride through Virginia’s Skyline Drive that he wanted to make it go on longer—nearly 500 miles longer, to be exact. In the coming months, his administration kicked off a massive roadway project to connect Skyline with Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and the Blue Ridge Parkway was born. Today, the Parkway remains one of the most beautiful drives in the country, connecting the Great Smoky Mountains to Shenandoah National Park. While its scenic overlooks get all the attention, the region’s restaurants offer a more intimate way to experience the landscape: through the very flavors of the berry bushes that line its trails, the trout that swim in its rivers, and the vegetation that gives its green mountains their striking hue. From elk burgers at a Native-owned diner to a foraged feast at an Afro-Appalachian restaurant, here’s a guide to the most incredible places to taste the flora and fauna of the Blue Ridge mountains.

6 Ways to Absorb Addison, Texas’ Arts and Culture

Sponsored by Visit Addison

Addison, Texas found acclaim in 1975 when residents pushed for alcohol to be served in public areas, when many nearby towns were dry. With an almost immediate surge in visitors, about five years later the Town launched an aggressive beautification program. Fast forward to present day, and every corner of this small town has a unique theme or landscape, and the city is teeming with public artworks. Conveniently, visitors can download the Otocast app, which offers guided audio and a full map of all the public artwork found throughout the town. The guided tours come complete with photos, descriptions, and audio of the artists discussing their work. Below is a list of places from which to start your journey.

6 Ways to Take in the History of Mesquite, Texas

Sponsored by Mesquite Convention and Visitors Bureau

Located just outside the skyscrapers and congestion of downtown Dallas, Mesquite has managed to hold onto its roots as an agrarian community while still keeping up with the times. Known as the Official Rodeo Capital of Texas, the city attracts hundreds of thousands of rodeo fans annually. But the rich town history is also a major draw for visitors wanting to get off the big city track, as exemplified by these six spots.

6 Ways to Soak Up Plano’s Art and Culture

Sponsored by Visit Plano

Plano, Texas may get its name from the flat local terrain—plano is the Spanish term for "flat"—but this Dallas suburb is anything but boring. The town makes up part of the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, so it’s an easy day or overnight trip if you’re visiting the big city. Located in the Northeast region of the Lone Star State, Plano is a mid-sized city with big personality, offering plenty of history and culture, with dozens of restaurants, bars, and shops. It also has an impressive collection of sculptures and public art pieces, which make for an excellent way to see the city.

9 Dallas Spots for Unique Art and Culture

Sponsored by Visit Dallas

In a city as big and vibrant as Dallas, it’s possible to miss a few things—like a giant eyeball statue or an enormous, happy robot, for example. This Texas city has a wonderfully quirky side; here are the best ways to take in its wide-ranging and often surprising arts and culture scene.

7 Sites of Small-Town History in Waxahachie, Texas

Sponsored by Visit Waxahachie

Waxahachie is a small Texas town that’s rich with history. Over thirty motion pictures have been filmed here, including the revolutionary Bonnie and Clyde and the Oscar-winning films Tender Mercies and Places in the Heart. It’s also been designated as the Crape Myrtle Capital of Texas, a place where you can witness the flower’s glorious blooming—especially during the Crape Myrtle Festival and Driving Trail every July. Despite its size (population: 36,735), Waxahachie boasts a wide array of historical places to visit.

6 Natural Wonders to Discover in Austin, Texas

Sponsored by Visit Austin

There is more to Austin than really, really, really good tacos and barbecue. The city is also home to a smorgasbord of natural wonders, many of which are free to enjoy. So burn off your breakfast tacos or brisket by swimming and strolling among Austin’s diverse wildlife and plants.

Discover the Secrets of Colorado’s Mountains and Valleys

Sponsored by Visit Colorado

Between all the world-class kayaking, hiking, and biking available in Colorado, you’re bound to find adventure-lovers around every corner this summer. But sometimes, what you really want is wide-open spaces, quiet vistas, and your footprints as your only company. In short, you want adventure on the secluded side. Luckily, in Colorado, there’s no shortage of hidden wonder. This itinerary will take you to a pristine mountain-top lake, under a triple waterfall, through majestic peaks on a historic railway, and over an iconic mountain pass on the state’s oldest aerial tram. There’s solitude to be found on this trip, but there’s also the thrill of finding some of Colorado’s best kept secrets. If you’re headed into the backcountry, follow these tips to stay safe and Do Colorado Right.

A Road Trip Into Colorado’s Prehistoric Past

Sponsored by Visit Colorado

Beneath Colorado’s majestic peaks, beside its roaring rivers, and nestled in the curves of its dramatic canyons, remnants of the prehistoric world have quietly waited for eons. Only over the past several centuries have people discovered these fossils, unlocking answers to the lives of ancient flora, the behavior of long-gone plants and animals, and the ever-changing landscape of this geologically dynamic state. Pieces of the prehistoric past that you can personally witness in Colorado include the continent’s longest dinosaur trackway, the remains of an ancient rainforest, the stumps of petrified redwood trees, and much more. A lot can happen over several hundred million years—but here in Colorado, none of it’s hiding.

A Feminist Road Trip Across the U.S.

Atlas Obscura has a tradition of exploring the stories of women who changed the world, from wildlife biologists and mountain climbers to Civil War spies and tattoo artists. To celebrate these daring women who struck out on their own, we’ve put together a cross-country road trip. Over 12 stops and more than 3,000 miles, this route will give you a front-row seat to women’s history in America.

All Points South

Sponsored by Travel South

Whatever hand the U.S. had in shaping world music, it had its feet planted firmly in the South. From New Orleans, where a confluence of West Africans laid the groundwork for the musical improvisation we call jazz; to Mississippi, where work-songs birthed the blues before the blues birthed rock ‘n’ roll; to Tennessee, where rock intersected with Appalachian folk songs to create country rock, this distinct artistic heritage was forged uphill, from the humblest of origins. Nonetheless, the musical legacy of unsung field hands, farmers, and blue collar workers coming up from the South would go on to change the world, and in no quiet way.

Asheville: Off the Beaten Path

Sponsored by Explore Asheville

With bustling food, music, and brewery scenes, Asheville has plenty of attractions—but stick to the downtown area alone, and you’re missing half the fun, at least. Surrounded by national forests, hideaway mountain towns, quirky arts centers, and more, some of Asheville's best spots lie beyond the downtown area. This itinerary will help you navigate America’s weirdest little mountain town like a local as you scale mountaintops, watch artisans at work, ride century-old trolley cars, and get fake-married at a real-live punk bar. Welcome to Asheville.

Restless Spirits of Louisiana

Sponsored by Louisiana Office of Tourism

If ghost stories help us confront a harrowing past, it’s no surprise that Louisiana is filled to the brim. From the swamplands to the pine forests, the state reverberates with tales of fortunes won and lost, untimely demises, and some of the darkest chapters of early American history. Whether you believe in the paranormal or not, the stories below reveal the hidden histories behind this mystifying state—place by place, spirit by restless spirit.

Eat Across Route 66

Created in 1926, Route 66 was once the primary way drivers headed West, and a network of local economies sprouted up along its path. But after the Interstate Highway System replaced many portions of the “Mother Road,” most of its associated attractions faded away. Intrepid travelers, however, can still seek out the remnants of this artery through America and even find a few new gems along the way. Along with the towering Muffler Men and the sprawling, changing landscapes that speed past your car windows, the restaurants and bars along Route 66 offer an enchanting glimpse into American history and culture. From an Illinois watering hole once frequented by Al Capone to an Albuquerque restaurant specializing in pre-Columbian cuisine to a steakhouse born of Tulsa’s once-booming Lebanese community, these spots showcase the delicious diversity of America’s most iconic road.

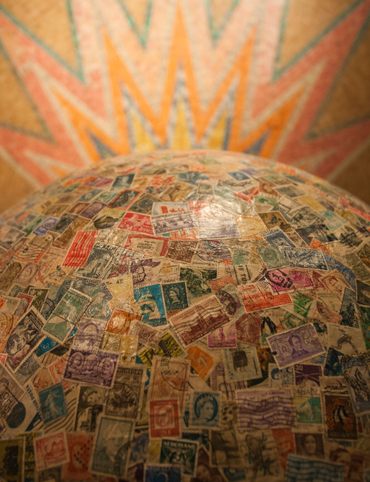

18 Mini Golf Courses You Should Go Out of Your Way to Play

Adventures filled with oversized characters, obstacles, and castles await—all you need to join is a putter and a ball. Yes, we're talking about miniature golf, the Lilliputian game with a big imagination. Since 2012, we—Tom Loftus and Robin Schwartzman—have been documenting the world of mini golf on our website A Couple of Putts. After putting our way through more than 300 courses, we’ve stumbled into becoming experts who design, build, and consult on all things miniature golf. With our keen eye for elements that make courses distinctive and magical destinations, we’ve created this world tour to showcase some of our personal favorites, as well as a few courses on our “must play” list. In keeping with the theme, here are 18 unique courses that span the globe. This wild assortment of putting places offer unique ways to interact with the past and present. Putt when ready!

4 Underwater Wonders of Florida

You probably know that Florida is famous for its shorelines, from the shell-stacked beaches of Sanibel Island to the music-soaked swaths of Miami. But many of the Sunshine State’s coolest attractions rarely see the light of day—they’re fully underwater. Here are some of the state’s strangest and most spectacular sites, beyond the beach, and below the surface.

6 Spots Where the World Comes to Delaware

Students of American history will know that Delaware is noteworthy for being the first state to ratify the Constitution of the United States, earning it the nickname “The First State.” But look beyond Delaware’s American roots, and you’ll find other cultural influences, tucked away where only the most enterprising of explorers will find them. From a Versailles-inspired palace to an English poet casually lounging in a garden, here are six places to help you travel the world without ever leaving the state.

Study Guide: Road Trip from Knoxville to Nashville

Sponsored by Graduate Hotels

East Tennessee boasts some of the state’s most beautiful highways and byways. Rather than rushing from one destination to the next, this is the perfect road trip to meander and stop along the way. Follow this suggested itinerary between Knoxville and Nashville, and you’ll discover lesser-known historical gems, stunning natural landscapes, and some memorable treats, all bookended by two of Tennessee’s truly great cities.

Rogue Routes: The Road to Pikes Peak

Sponsored by Nissan

It wouldn’t be quite accurate to say this route from Salt Lake City to Colorado Springs is paved by rogue trailblazers. Indeed, much of it remains unpaved, not so much out of disregard as in homage to the rugged landscape that has inspired so many to strike out against the banal, to write their own script. From pioneering artists to obsessive curators and bold builders, this route follows in the footsteps of a bold few—watch your step.

6 Wondrous Places to Get Tipsy in Missouri

Celebration or desperation aside, these six spots in Missouri are proof that imbibing is only half the fun of bar culture. From a mountaintop drive-through golf-cart bar to the state's oldest waterhole hole—nestled more than 50 feet underground in a limestone cellar—the “Show-Me State” has no shortage of boozy fun to show you (as long as you're 21+, of course).

Rogue Routes: The Road to Carhenge

Sponsored by Nissan

Artistic visionaries and the spirit of rogue ingenuity define this route that starts in Denver, winds through the plains of southeastern Wyoming, and finishes in Alliance, Nebraska. It takes you off the beaten path to discover quirky art installations, historic monuments, local flavors, and natural wonders. This route of 11 inspiring spots is certain to spark the autonomous flame for all who take it on.

4 Pop-Culture Marvels in Iowa

Iowa is the pantry of America, giving over the vast majority of its land to agriculture and producing more corn and pork than any other state. But the state has also proven fertile ground for pop culture, as well. The landscape has inspired movies, films, songs, paintings, and novels while spawning movie royalty in the form of a certain Duke. Bask in the wonderful corniness of these four pop-culture touchstones in the Hawkeye State.

7 Stone Spectacles in Georgia

At the heart of every peach rests its stone center, or pit. So perhaps it’s fitting that Georgia, the Peach State, holds a wealth of stone-based treasures of a different sort. In Walker County, a labyrinth of limestone passages leads to the deepest cave drop in the continental United States. In Calhoun, a rock garden of spectacular sculptures hides behind a church. And in Savannah, two gravestones appear on an airport runway. Whether carved by hand or nature, these stone wonders truly rock.

6 Stone-Cold Stunners in Idaho

It turns out that no one really knows how Idaho got its name. It's been thought that the name came from Shoshone, but in truth it may have just been made up by a somewhat shady politician. Regardless of what you call it, the Gem State is sparsely populated and unapologetically wild, and full of wonders—especially geological ones.

8 Historic Spots to Stop Along Mississippi's Most Famous River

The Magnolia State is also famous, of course, for being one of the locales ribboned by the squiggly Mississippi River, which stretches more than 2,300 miles from Minnesota to Louisiana. Combined with the Missouri River, one of its tributaries, the Mississippi is the fourth-longest river in the world, trailing the Nile, Amazon, and Yangtze. The river is well worth a visit—and if you’re roaming the state that shares its name and want to hug fairly close to the shore, here are eight places to pop in along the way.

5 Incredible Trees You Can Find Only in Indiana